The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) is an international treaty administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) that streamlines the process of seeking patent protection in multiple countries. Instead of filing separate patent applications in each country of interest, a PCT application allows an inventor to file one “international” patent application which has effect in over 150 PCT contracting states simultaneously. This system, often called the international patent system under the PCT, simplifies initial filing formalities and defers much of the cost and effort of pursuing patents in many countries. Importantly, the PCT does not itself grant an “international patent” (no such single global patent exists). The granting of patents remains under the control of each national or regional patent office during the “national phase” of the process. For U.S. applicants (e.g. businesses or inventors in the United States), the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) can act as a PCT receiving office to start the process, and the PCT framework is integrated into U.S. patent law. This article explains in accessible terms how the PCT works, its timeline and costs, and key requirements for U.S. applicants using the USPTO as the receiving office.

The PCT is used by companies of all sizes, universities, and individual inventors around the world when they seek international patent protection. It has become a cornerstone of international patent strategy. Every year there are hundreds of thousands of PCT international applications filed. For a business owner, the PCT is important because it provides a cost-effective and time-saving path to pursue patent rights in multiple countries. By filing one international application under the PCT, an applicant can essentially lock in a single earliest filing date (priority date) for an invention across many countries, and then delay the decision and expense of filing in each country by up to 18 additional months compared to the traditional route. This extra time can be invaluable for evaluating the invention’s commercial prospects and deciding in which countries to seek patents. In short, the PCT helps businesses seeking patent protection in multiple countries by simplifying the application process and giving them more time and information before entering numerous separate patent offices.

The Patent Cooperation Treaty is an international treaty first signed in 1970, now with more than 150 member countries (PCT contracting states). It created an international patent system that makes it possible to seek patent protection for an invention simultaneously in a large number of countries by filing a single “international” patent application. In essence, a PCT application is a unified initial filing that can later be pursued in many different countries. Any inventor or company who is a national or resident of a PCT contracting state can file a PCT application. U.S. applicants are eligible, as the United States has been a contracting state since 1978. A PCT application may be filed with your national patent office (the USPTO) or directly with WIPO’s International Bureau, which both act as PCT receiving Offices.

It is important to understand that the PCT itself does not grant a patent. Instead, it delays and coordinates the process of pursuing patents in the PCT contracting countries. The applicant must still enter the national phase in each country or region where protection is desired, and pursue the application under that country’s national law. The PCT thus provides a unified filing and preliminary examination process (the international phase), followed by separate patent applications in each country/region (national phase) where you want patent rights for the claimed invention.

By filing a PCT international application, an inventor effectively secures a filing date in all PCT member countries at once, and gains the benefit of a centralized search and preliminary examination, before deciding on separate national applications in individual countries. The system is administered by WIPO in Geneva, and is used worldwide as a standard route for international patent filings.

For business owners contemplating global markets, the PCT system offers several advantages over filing separate national patent applications in each country:

You file one application, in one language, and pay one set of initial fees, instead of filing many applications with different patent offices simultaneously. This simpler and more cost-effective approach reduces duplicate effort. WIPO handles a formality examination of the application, so if your PCT application meets the PCT’s form requirements, it cannot be rejected on formal grounds by any national office later.

As part of the PCT’s international phase, a qualified patent office will conduct an International Search and provide a report on relevant prior art along with a Written Opinion on the invention’s patentability. This happens early, before you spend money on multiple national filings. The search report and opinion give valuable insight into the strengths and weaknesses of your claimed invention, allowing you to make informed business decisions (e.g. whether to proceed in certain countries, or perhaps to modify your claims). You even have an option for an International Preliminary Examination (an additional, interactive examination – see below) to further assess or bolster your application before national phase entry.

Perhaps the biggest practical benefit is time. Under PCT, you usually gain an additional 18 months after your initial filing before you must incur the expenses of national filings. In a typical scenario, you have 12 months from your earliest patent application to file a PCT (this 12-month rule comes from the Paris Convention priority period), and the PCT gives you up to 30 months from the priority date (in most countries) to enter the national phase. That 30-month deadline is 18 months longer than the 12-month Paris Convention deadline would have been if you filed separate foreign applications directly. During these 18 extra months, the international search report and publication can help you gauge the invention’s patentability and market potential. You can use this time to seek investors, evaluate commercial interest, or decide to drop the application if prospects look unfavorable – thereby saving the cost of filings in many countries. In short, the PCT buys you time and information.

While the PCT application is pending, it maintains your rights in all designated states without further action. You do not have to pay separate filing fees or hire local attorneys in each country at the start. The international application is treated as a pending application in all PCT countries simultaneously. This global effect means no need to rush translations or incur local fees early on, and it preserves the option to proceed in any PCT country later.

When you do enter national phases, the PCT search report and any international examination report accompany your application into each patent office. National examiners consider these PCT work products, which often reduces duplication of effort. In some cases, if the PCT results are favorable, national phase examination may be accelerated or smoother. Many patent offices participate in the Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH), allowing you to fast-track examination by leveraging a positive PCT opinion or report. Essentially, the PCT centralizes the early search and (optional) examination, which can make the subsequent national phase more efficient.

At 18 months from the priority date, the PCT application is published internationally by WIPO. This publication puts the world on notice of your invention. Competitors and potential licensees can learn of your application by searching WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE database once it’s published. Early publication combined with the credibility of a WIPO search report may help attract partners or deter infringers, since third parties can evaluate the potential patentability of the claimed invention based on the PCT publication. You also have the option to indicate on PATENTSCOPE that you seek licensing opportunities, effectively advertising your invention to the world.

In summary, the PCT offers simplicity, time efficiency, and strategic advantages for applicants seeking patents in multiple countries. It is simpler, easier and more cost-effective than filing separate applications country-by-country, especially for U.S. businesses looking to expand their patent protection globally.

To navigate the PCT process, it helps to know some basic terminology and the entities involved:

This is the patent office where you file your PCT application. Each PCT member country’s patent office can act as a receiving Office for its own nationals/residents. For example, the USPTO is the receiving Office (RO/US) for U.S. applicants. WIPO’s International Bureau can also directly receive applications in some cases. The receiving Office checks that your application meets minimum requirements (e.g., that you’ve included at least a description and the applicant is entitled to file) and then assigns an international filing date if all formal requirements required by PCT Article 11 are met.

The date your PCT application is officially filed at the receiving Office. If the application meets the formality requirements, the international filing date is accorded and serves as the effective filing date for all designated countries. This date is very important; it’s equivalent to a filing date in each PCT country. If you are claiming priority from an earlier application (e.g., a US patent application), you must file the PCT within 12 months of that earlier application’s date to preserve your priority.

This is WIPO’s office in Geneva that centrally administers PCT applications. The IB acts as a clearinghouse: it publishes the applications, communicates documents to all designated countries’ patent offices, and keeps the master file. Once you file with a receiving Office, the application data is sent to the IB. The IB is also a possible receiving Office itself for applicants who choose to file directly with WIPO. The IB handles the international publication of PCT applications at 18 months and stores the application in its database.

This is the patent office that performs the international search on your PCT application. ISAs are major patent offices appointed to conduct PCT searches (for example, the USPTO, European Patent Office, JPO, and KIPO are ISAs). Not every ISA is available for every applicant, which ISA is competent can depend on where you filed your PCT. U.S. applicants filing at RO/US currently can choose the USPTO itself as ISA or one of several other offices, such as EPO, KIPO, Australia, Singapore, etc., subject to agreements. The ISA will search patent literature and technical publications to find prior art relevant to your invention.

This is the report prepared by the ISA listing prior art documents (patents, publications) that may affect the patentability of your invention. The ISR gives for each reference an indication of its relevance to novelty or inventive step. It’s essentially a focused prior art search result. The ISA aims to issue the ISR along with a Written Opinion typically within about 16 months from your priority date (or about 9 months from the PCT filing date). The ISR is later published by WIPO, usually together with your application at 18 months.

Along with the ISR, the ISA provides a written opinion analyzing whether your claimed invention appears to meet the criteria of novelty, inventive step (non-obviousness), and industrial applicability. This written opinion is preliminary and non-binding, but it’s very useful: it explains the examiner’s view on each claim’s patentability in light of the prior art found. As an applicant, you don’t have to respond to the written opinion during the international phase, unless you choose to request further examination, but you can use it to guide amendments. If you take no further action, this written opinion will later be converted into an “international preliminary report on patentability (Chapter I)” at the end of the international phase, which is communicated to all the national offices.

WIPO publishes the PCT application promptly after 18 months from the earliest priority date. The publication includes the description, claims, any drawings, and also the ISR (if it’s ready in time) and the applicant’s abstract. It is published in one of the 10 languages of publication. For example, if you filed in English, it publishes in English. After publication, the content is publicly available on WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE database. Prior to 18 months, the PCT file remains confidential, unless you request early publication or access. Publication at 18 months is a standard practice also for regular national applications in many countries, including U.S., aligning with the principle that patent applications are made public 18 months after filing.

If you decide to proceed with Chapter II, International Preliminary Examination, you will file a demand for examination and usually amend your application or argue against the ISA’s opinion. The IPEA is an office that conducts this second-round examination. Not all applicants use Chapter II, but it can be beneficial if the ISA’s written opinion was negative and you wish to improve the application before national phase. The International Preliminary Examining Authority will consider your amendments and arguments, possibly correspond with you or even hold an interview, and then issue an International Preliminary Report on Patentability (Chapter II).

IPRP Chapter I: If you do not request a Chapter II exam, the WIPO will issue an IPRP (Chapter I) which is basically a copy of the ISA’s final written opinion (translated into English if necessary) at the end of the international phase. This report, along with the ISR, is sent to all designated offices for their reference.

IPRP Chapter II: If you do file a demand for preliminary examination (Chapter II), the outcome is an International Preliminary Report on Patentability (Chapter II) issued by the IPEA. This report will state the examiner’s patentability opinion on each claim after considering any amendments you made. Like the Chapter I report, it is non-binding on national offices, but it provides a stronger basis if positive. A favorable Chapter II IPRP can significantly bolster your case going into national exams. National patent offices often give the IPRP weight, even though they will do their own examination. If the report is negative, it at least forewarns you of likely issues.

This refers to the stage after the PCT international phase where you actually pursue patent grants in individual countries or regions. “Entering the national phase” means filing the necessary documents and fees with a national or regional (e.g., the European Patent Office) patent office, based on your PCT application. The national phase deadline is typically 30 months from the priority date, though a few offices have 31 months or allow slight extensions. During national phase, each patent office examines the application under its own national law and requirements. The international stage PCT documents and analysis will be available to them to consider, but each office makes its own decision on granting a patent. Essentially, the PCT application splits into multiple “daughter” applications in the national phase, one in each desired country/region.

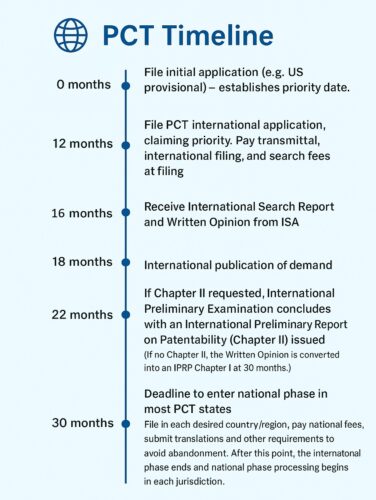

For clarity, we’ll consider a typical scenario for a U.S. applicant and outline the PCT process timeline with key milestones, requirements, and fees. Assume you have an initial U.S. patent filing (for example, a provisional or non-provisional application) and you want international protection:

Initial Application Filed. Often, applicants first file a national application in their home country to establish an initial filing date. For instance, you might file a U.S. provisional application or a U.S. non-provisional application. This date is the priority date for subsequent filings. Under the Paris Convention, you have 12 months from this date to file a PCT application to claim its priority. If you don’t have an earlier application, your PCT filing itself can be the first filing and the PCT filing date is the priority date.

Before 12 months from the priority date expires, you must file your PCT international application if you want to claim priority to the earlier national application. For US applicants, this PCT filing is often done via the USPTO as the receiving Office (RO/US). Requirements at filing: You need to submit the PCT Request form (which is basically a cover sheet with bibliographic data, inventor/applicant information, etc.), a specification (description, claims, drawings if any, abstract) – which can be a direct copy of your prior application or updated, and usually an abstract. You also must pay the international fees at this stage. Typically, there are three types of fees due upon PCT filing:

Transmittal Fee: a small fee for the receiving Office (USPTO) handling the filing. For example, the USPTO’s transmittal fee is a few hundred dollars (often around $240 for electronic filing; check current USPTO fee schedule).

International Filing Fee: a WIPO fee for processing the application internationally. This is a fixed fee for all applicants worldwide, denominated in Swiss Francs (CHF). As of the PCT Applicant’s Guide, the base international filing fee is 1,330 Swiss francs (about $1,400, but varies with exchange rates) for up to 30 pages. There is an additional fee per page if your application exceeds 30 pages. This fee is paid to the receiving Office, which is then forwarded to WIPO.

Search Fee: the fee for the International Searching Authority to perform the prior art search. This amount depends on which ISA is chosen and can range roughly from $150 to $2,000. For example, if the ISA is the USPTO, the search fee (per USPTO’s fee schedule) might be around $2200; if the ISA is the European Patent Office, it’s about EUR 1,775; some other ISAs are less costly. The applicant typically selects the ISA in the request form. The search fee is paid at filing to the receiving Office, which is forwarded to the ISA.

Optional Fees: If you file electronically using approved software (which most applicants do via ePCT or USPTO’s electronic filing system), you may receive a reduction in the international filing fee. Also, if you qualify as a small entity or reside in certain countries, fee reductions might apply (e.g., certain developing country applicants get 90% reduction in WIPO fees).

After filing, an international filing date is accorded (assuming all formal requirements are met). The USPTO (RO/US) will assign an international application number and confirm your international filing date, which, crucially, is the date that will count as the effective filing date in all PCT countries. If something is missing, the receiving Office may give you a chance to correct it and still get the date; the conditions for obtaining a filing date are set by PCT Article 11.

The receiving Office processes your application, confirms all parts are present, and then forward it to the International Searching Authority (ISA) you selected. The ISA will typically start the international search for prior art. You will receive an acknowledgment of your PCT filing (with the PCT number and filing date) and later possibly a notice if anything needs to be fixed (e.g., missing pages or fee issues). If all is in order, you mostly wait for the search results. The priority document (your earlier application) also needs to be provided to WIPO, and is often the receiving Office will handle transmitting an electronic copy if the priority application was, e.g., a US application, via the priority document exchange system. Otherwise you may need to furnish a copy or request retrieval).

The ISA aims to issue the International Search Report (ISR) along with the Written Opinion (WO) by about 16 months from the priority date or roughly 9 months after the PCT filing. The ISR is a list of prior art references (patents, publications) relevant to your claimed invention, with indications of their relevance. The Written Opinion is a detailed initial examination analysis of your claims against the prior art, essentially stating whether your invention is novel, non-obvious, and industrially applicable, and explaining any issues claim by claim. This written opinion is not public at this point and is not an official rejection, but it gives you a preview of what an examiner thinks. In response to the ISR and written opinion, you have the option to do nothing (e.g., if the report is favorable), or prepare and file claim amendments and/or submit arguments against any patentability issues raised in the report.

Whether or not you have the search report by then, at 18 months from your priority date, WIPO will publish your PCT application electronically. The publication (identified as “WO [year]/[#####]”) includes your application text and any figures, and if the International Search Report is ready, it is published as an appendix. If the ISR wasn’t ready by 18 months, the application still publishes, and the ISR will be published separately later when available. The publication is in the public domain via PATENTSCOPE. From this point on, your invention’s details are public worldwide, and you have “patent pending” status internationally. Third parties can now see the results of the search, which can inform their actions or interest.

Costs at this stage: There is no additional fee for publication itself, the filing fee covered WIPO’s processing. However, if your application was filed in a language not accepted by your chosen ISA, you might have paid a translation cost for search purposes earlier. Most U.S. applicants file in English, so that’s usually not an issue since USPTO or EPO as ISA accept English. Also, if you decide around this time that you want to withdraw the application (to avoid publication, perhaps because the invention is no longer pursued or the ISR was very negative), you must do so before the 18-month mark. Otherwise, publication will occur and the application will be public.

If you choose to use the optional Chapter II procedure and request an International Preliminary Examination, you need to file a demand by the later of 22 months from the priority date or 3 months from the transmittal of the ISR. In practice, since the ISR usually arrives by 16 months, you have until around 19–22 months to decide on Chapter II.

Why file a demand? This is useful if the Written Opinion from the ISA was negative or if you want to amend the claims and get a second opinion on patentability before entering national phases. By filing the demand, you get to engage with an International Preliminary Examining Authority (IPEA) and potentially argue your case or amend claims.

Requirements and fees for Chapter II: You must file a demand form (there’s a PCT form for Chapter II demand) and usually submit any claim amendments (Article 34 amendments) you want to make in light of the search report. You’ll need to pay:

Once the demand is filed and fees paid, the IPEA will perform an international preliminary examination. This can involve at least one office action in the international phase: the examiner will review your amendments/arguments in view of the objections raised in the written opinion, possibly raise new issues, and may communicate with you. You have a chance to respond, and there may even be an interview with the examiner. Chapter II provides the only opportunity to have dialogue with an examiner during the international phase. Many applicants skip Chapter II to save cost, but those who want a cleaner application going into national phase or who want to test amendments globally, often use it.

If Chapter II was used, the IPEA will issue the International Preliminary Report on Patentability (IPRP Chapter II) by around 28 months from the priority date. This report will state, for each claim, whether it meets the criteria of novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability in the examiner’s opinion. It will be shared with all the elected Offices: the countries you intend to enter. If you did not file a Chapter II demand, then an IPRP Chapter I will be prepared, which is essentially a copy of the ISA’s written opinion. Either way, by 30 months at the latest, the international phase concludes with a dossier of search and examination documents that national offices can use.

Thirty months from your earliest priority date is the typical deadline to enter the national phase in each country or regional office you choose. “Entering national phase” means you must take action in each desired jurisdiction to continue prosecution of the application there. What must you do? According to PCT Article 22 and related national laws:

It’s important to meet the 30-month deadline. If you miss it in a given country, the application can lapse in that country, and be treated as withdrawn/abandoned. Some jurisdictions have grace periods or remedies, for example, the U.S. allows the acceptance of a late national stage entry after 30 months if the delay was unintentional, via petition and payment of a late fee under 35 U.S.C. § 371(d). But such leniency is not universal, many countries strictly bar late entry. Therefore, patent applicants should diarize the 30-month date and take action in time.

This is where the major expenses occur. You now must pay separate fees in each selected country. Costs include official filing fees (vary by office), translation costs (if needed), and local attorney fees for handling the filings. The national phase fees are the most significant pre-grant costs; they can far exceed the earlier PCT costs. However, some national offices offer reduced fees for PCT entries compared to direct filings, recognizing the work already done internationally. For example, if an office benefitted from the international search, they might charge a lower search/exam fee nationally. Nonetheless, applicants should budget carefully; entering, say, Europe, China, Japan, Canada, and Australia could collectively cost tens of thousands of dollars in filing and translation fees.

At the 30-month juncture, you effectively decide in which countries or regions you want to pursue actual patents. Many applicants will choose a handful of key markets based on business strategy. The PCT helped delay this big expense and decision until this point. Now, those national applications will be prosecuted individually in each jurisdiction’s patent office.

After entry, each patent office will process the application as a national application (often assigning it a local application number). They will usually refer to the PCT search report and may use the PCT examiner’s work as a starting point, but they will apply their own patent law standards. For example, the USPTO will have its examiners examine the application under U.S. law (35 U.S.C. §§ 101, 102, 103, 112, etc.), the European Patent Office will examine under the European Patent Convention, and so on. You or your local attorneys will correspond with each office, respond to rejections, and prosecute the application to grant as you would with any patent application.

The timeline and outcome now vary by country: some offices might grant a patent within a year or two, others might take longer. Each resulting patent is a separate patent, enforced in that country or region. Maintenance fees will have to be paid in each jurisdiction to keep those patents in force.

Below is a quick visual summary of key PCT timeline points using the earliest priority date as time zero:

Throughout this timeline, keep in mind specific national rules. For instance, some countries have slightly different deadlines: a few allow 31 months, like the EPO. You can consult the PCT Applicant’s Guide for any particular country’s requirements and time limits. WIPO provides detailed national chapters in the Guide outlining each state’s rules.

U.S. business owners filing via the USPTO should note a few specific points:

The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) is a powerful tool for U.S. businesses and inventors looking to protect an invention in multiple countries. It provides a unified international patent application process that simplifies filing and delays the need to make expensive decisions about country-by-country patent filings in the over 150 PCT contracting states. By using the PCT, a company can seek patent protection in multiple countries simultaneously in a cost-effective manner.

It is important to remember that ultimate patent protection remains territorial. There is no international patent that is issued. You must pursue patents in each target country or region, under their laws and procedures, to actually get patents granted. The PCT greatly facilitates and coordinates this process, but it doesn’t eliminate it.

In planning an international patent strategy, business owners should consider the PCT’s benefits: one application, one search, delayed costs, and global reach. In virtually all cases where protection in multiple countries is desired, the PCT is the recommended route. It is a flexible, user-friendly international treaty that makes the complex world of international patents more accessible to innovators. If you are considering pursuing foreign patent rights, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney