Design Patents - An Overview

There is more than one type of patent. In the US patent system, there are

utility patents,

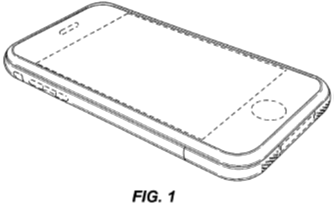

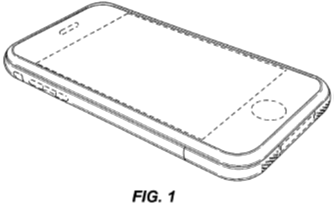

plant patents, and design patents, each of which provide different kinds of patent protection. Design patents are important intellectual property tools in the right circumstances. Design patents cover the “ornamental appearance” of an “article of manufacture” (i.e., a manufactured article). Stated differently, a design patent covers the outward appearance or “look” of a manufactured article, not its function aspects. Though not as well-known as utility patents, design patents can provide meaningful patent protection for a vast array of manufactured articles, including fashion patterns on textiles, mobile phone body designs, clamshell and other packaging designs, car body designs, toy designs, silverware, hand tools, individual component designs of larger manufactured articles, and much more. A design patent can cover a shape of the article, surface ornamentation, exterior materials, and/or other features in the outward appearance of the article. A famous design patent example is the well-known Apple iPhone set forth below [

design patent No. D558756]:

iPhone Design Patent

Design Patent vs Utility Patents - Scope of Protection

The protection provided by a design patent is for the ornamental design of the article of manufacture, rather than its function as provided by a utility patent. Put a different way, a design patent protects the way an article of manufacture works and does not provide protection for the functional features of the article. Design patent protection prevents knock-offs and close approximations of a product's outward, ornamental appearance. Despite the nature of design patent coverage, the scope of protection provided by a design patent can have breadth to cover variations in the design, if the design patent application is prepared and drafted strategically.

A Design Patent can Complement a Utility Patent or Trade Dress Protection

Design patents can also complement utility patent protection and trade dress protection. For example, a new tool invention may be patentable through both utility patent and design patent. It may provide new functionality worthy of a utility patent, and the version sold to consumers may also have ornamental design elements (e.g., a handle design) that are protectable through a design patent. Also, the same ornamental design elements may be protected by design patent and trade dress protection (which is a version of trademark protection) if they are not functional.

Design Patents do not Require Acquired Distinctness, Unlike Trade Dress

A design patent can be acquired relatively quickly for a novel and non-obvious design, whereas trade dress requires that that the design acquire distinctiveness over many years that associates the design with the manufacturer of the design in the mind of the consumer. Acquiring distinctiveness in trade dress can take significantly longer than acquiring a design patent. Additionally, design patents carry strong remedies for infringement that have fewer defenses and are distinct from those for trade dress infringement. Design patent infringement remedies, and other considerations relevant to design patents are discussed in more detail here.

Design Patent Application Process

In order to be issued a design patent, a creator of a new ornamental design must prepare and file a design patent application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. A design patent application includes specialized drawing disclosure, a written specification, and a single claim. The parts of a design patent application are specialized and a thorough understanding of patent law is required to properly prepare the application.

Design Patent Drawings

Design patent drawings are the primary disclosure of the ornamental design claimed in the design patent application. The design drawings are specialized and must provide views of all aspects of the article of manufacture. In other words, drawings of all sides of the article of manufacture must be provided in order to provide the public and the patent office with a complete understanding of the design protection sought through the design application. The design patent drawings must have sufficient information to demonstrate the ornamental features of the design. Typically, design patent drawings include surface shading and other surface texture indications, such as hatching. The drawings must show any surface ornamentation applied to the article of manufacture in order for such ornamental features to be included in the claimed subject matter. It is critical that design patent drawings are prepared by a patent attorney due to both their specialized nature and the fact that the claimed subject matter of a design patent is almost entirely defined by the design drawings.

Claiming Ornamental Appearance of Functional Features or Articles

In a design patent application that covers an invention that includes both utility and ornamental appearance, the design patent protects the ornamental features, but not purely functional features. Functional features may have an ornamental appearance and can be included in the claimed subject matter of a design patent. For example, a hood is one of the utilitarian features of an automobile, but many hoods have an ornamental appearance (e.g., sculpted lines and contours, decals, bulges and scoops, etc.). Thus, the ornamental designs and aspects of functional features and articles can be protected. Only when functional features are purely functional are they excluded from the scope of design patent protection.

Disclaimers from the Claimed Subject Matter

In design patent applications, features of the article of manufacture may be disclaimed from the design patent protection sought by the applicant. Features in the design patent application drawings may be shown in dashed or broken lines, which indicates that such features are not included in the claimed subject matter and shall not be included in the legal protection provided by the design patent. The design drawing of the Apple iPhone shown above, demonstrates the use of broken lines to disclaim the screen, home button, and other features of the iPhone design. The disclaimers allow the claimed subject matter and legal protection of the design patent to be broader because the design patent claim does not require a rectangular screen or round home button. The features shown in broken lines are not required to be present in competitor's product for design patent infringement to occur. Disclaimers in a design application can serve to broaden the scope of design patent protection.

Design Patent Specification

The written specification of a design patent application is relatively brief compared to that of a utility patent application. The design patent specification includes figure descriptions for the drawings, a statement with respect to any disclaimers included in the drawings, and a single claim to the design shown in the drawing disclosure. There may be more than one embodiment of the design, such as multiple variations on the design with different disclaimers (e.g., a first embodiment in which the home button is disclaimed and a second embodiment in which it is not). The figure descriptions must include a description of each claim, including each drawing for each embodiment included in the application.

Filing a Design Patent Application

Once a design patent application is properly prepared with a complete drawing set with the necessary surface shading and ornamentation, the appropriate disclaimers, and the required figure descriptions, the design application can be submitted to the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Once the design application is submitted, the application has an official filing date and the claimed design design has patent pending status. The patent office will then assign the design patent application to a patent examiner in the art unit that corresponds to the subject matter of the application. The design patent application process includes a patent examiner's evaluation of the design in view of the relevant prior art, which is similar to the examination process in a utility patent application.

Patent Examiner's Search and Analysis of the Claimed Subject Matter

The patent examiner conducts a search of the prior art to find both utility and design patents and published patent applications that are substantially similar to the claimed design and precede the effective filing date of the design application. The patent examiner may also search for products and other information that are publicly known. Once the search is completed, the patent examiner compares substantially similar prior art to the ornamental appearance and ornamental features of the claimed subject matter to determine whether the claimed design is sufficiently distinct from prior designs to be considered novel and non-obvious. Novelty and non-obviousness are the key hurdles to issuance of design patents, and are discussed in further detail below.

Patentability in the context of Design Patents.

The general test for whether a design is patentable is nominally the same test applied to utility patents: the design must be both novel and non-obvious in view of the relevant prior art. The primary criteria for design patentability are novelty and non-obviousness, but with respect to the ornamental design, without any regard for utility or functional features.

Design Patent Novelty

Under US patent law, an ornamental design submitted in a design patent application must be new and significantly different from any prior designs known in the field. This means the design must not have been previously disclosed to the public in any form, such as earlier patents, publications, or products on the market. The assessment of novelty in design patent applications is based on the overall visual impression of the claimed ornamental design, rather than discrete elements. The patent office compares the ornamental design with prior art designs to determine if the overall visual appearance of the design is distinctively different. The novelty test for design patents is not about technical advancements or functional aspects, as is the case in utility patents, but rather is about the uniqueness of the ornamental features. Even small changes in ornamental features (e.g., shape, configuration, or surface ornamentation) can render a design novel, provided these changes create a different overall visual impression from what already exists in the public domain. This requirement ensures that design patents incentivize true innovation in the field of industrial and aesthetic design and protect designers' creative efforts, while also keeping the door open for future innovation by not overprotecting common or trivial design features. The novelty test is relatively straight forward and requires that the design was not previously made public by a third party through sales of the design, a design patent issued for the design, or through other means.

Design Patent Non-Obviousness

Non-obviousness in the design patent context is stated as follows: whether it would have been obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the relevant art to have “combined teachings of the prior art to create the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.” This test comes from the case of

Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2012) as stated by the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which is the appellate court that generally hears all patent appeals. Every applicant for a design patent must overcome this test. As a practical matter, obviousness rejections in design patent applications are not frequent, but they do occur. For instance, where an ornamental design is used in one context and then copied for use in another context, the new application of the design may be considered obvious in view of the earlier application of the design. In

Neo-Art, Inc. v. Hawkeye Distilled Products, Co. ,654 F. Supp. 90 (C.D. Cal. 1987), the court found that an alcohol container made to look like an intravenous fluid dispenser was obvious because there were pre-existing intravenous fluid dispensers with closely similar ornamental features. So, unless there is a pre-existing design that has the same or highly similar ornamental features to the applied-for design, like the example in the Hawkeye case above, an obviousness rejection of the design patent application is unlikely.

Design Patent Term

Under the patent laws of the United States, the term lengths of design patents and utility patents are notably different, reflecting their distinct purposes and scopes of protection. Utility patents, which cover new and useful processes, machines, articles of manufacture, or compositions of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, provide patent protection for a term of 20 years from the filing date of the application. This duration is intended to provide a substantial period for inventors to capitalize on their functional innovations. On the other hand, design patents, which protect the ornamental design of an article of manufacture, have a shorter term of 15 years from the date of grant. This change from a 14-year term to a 15-year term came into effect for any design patents issued from applications filed on or after May 13, 2015. The shorter term for design patents recognizes the often more ephemeral nature of the value of aesthetic designs, which move in and out of fashion or favor. This distinction in patent terms is also based in the recognition in the patent system of the relative value provided by an ornamental design versus a utilitarian innovation that provides long term practical value to the public.

No Maintenance Fees or Early Expiration in Design Patents

It is worth noting that design patents do not require maintenance fees. Once the design patent issues, it is in force for the full 15 years from the date of issue. This is in contrast to utility patents. Significant maintenance fees must be paid on three separate occasions in order to keep utility patents valid and enforceable. A failure to pay the maintenance fees, results in the lapse of the utility patent.

Pursuing Foreign Design Patent Rights

A US design patent application can provide foreign priority for pursuing design patent protection or similar rights in foreign countries. Foreign design application must be filed within six months of the filing date of the US design patent application in order for foreign priority to be properly claimed. Foreign design patent rights can be pursued directly in foreign countries under the Paris Convention treaty to which most countries are party. There is also an international design application process under the Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs, which provides a centralized filing system for design patents amongst ninety-six countries, including the US, Canada, Europe, and China. US design patent applications can also claim foreign priority to design applications filed in foreign countries.

Infringement of Design Patents

A design patent is infringed if an accused design violates the “ordinary observer test”. Generally, the ordinary observer test is met if an ordinary observer would confuse an infringer's design with the patented design, and the patented design's novel elements are found in the infringing design. In other words, the infringing design must resemble the patented design closely enough that the ordinary observer would believe they are the same design, but the similarities cannot be based on pre-existing or run-of-the-mill designs. The ordinary observer test has developed over time, beginning with a Supreme Court decision in 1871, which held:

Two-Step Analysis of Ornamental Designs

A relatively recent decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals of the Federal Circuit in the case of

Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc) has clarified what is required for the above test. According to the Egyptian Goddess case, there are two steps to the inquiry. The first step is a determination of whether the accused design and the patented design are plainly dissimilar.

Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 678. If the two designs are dissimilar, the inquiry ends, and there is no infringement. However, if the two designs are not plainly dissimilar, then a second inquiry is made which involves comparing both “the claimed and accused designs with the prior art.”

Id. This inquiry seeks to determine which features of the claimed design are different from those that existed in earlier public designs (known as “prior art”), and whether those different (i.e., “new”) features are present in the accused design. Thus, the first question is whether the accused design and the patented design are plainly dissimilar; and if they are not, whether the ornamental aspects of the patented design that are not found in the prior art are also found in the accused design.

Infringement Must be Based on Novel and Ornamental Aspects

If the confusion results from aspects of the design that were present in the prior art, there is no infringement. For example, if a person patents a new design for a lamp that has a novel body design, but has an ordinary lamp shade that is similar to other lamp shades, the patent can only be infringed by a lamp design that includes a body that is the same or sufficiently similar to the patented body design, without regard to the similarities of the shades. Only those features that represent a design choice by the inventor not based on strictly functional necessities are considered in the infringement analysis. Strictly functional aspects cannot be a basis for design patentability or infringement, but in many cases functional aspects represent a choice between different alternatives, and may therefore be protectable. This is very different from trade dress infringement, where any functionality in the design precludes protection.

Remedies for Design Patent Infringement

The owner of a design patent must mark the products covered by the design patent with the design patent number in order to be able to recover damages for infringement. This marking places potential infringers on constructive notice of the design patent. Then, if the design patent is infringed, the patent holder is entitled to pursue injunctions barring further infringement of the patent, including preliminary and permanent injunctions, and all of the same damages remedies that are available in the case of utility patent infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 284. These include compensatory damages to cure the damage done to the patent holder by the infringement with court costs. The court also has the discretion to increase the damages up to three times the amount of damages demonstrated in exceptional cases, such as where the infringer's actions are willful and egregious.

Additional Disgorgement Remedy for Design Patents

In addition to these standard remedies, design patents carry an additional powerful remedy under

35 U.S.C. § 289, which gives the patentee the ability to pursue the infringers profit for all sales of the infringing article. This is a punishing remedy that acts as a strong disincentive against infringement, which is not available for utility patents. The disgorgement of profits remedy has been interpreted by the court to be limited to the particular article of manufacture covered by the design shown in the patent, and not necessarily a composite product of which the patented article forms a part. See

Samsung Elecs. Co. v. Apple Inc., 137 S. Ct. 429, 436 (2016). In cases where the design patent covers a component of an end product, the court will not necessarily award the entire profit made on the end product. The disgorged profits will more likely be the demonstrated proportion of the total profits that are attributable to the patented article.

Contact Sierra IP Law for Assistance with Design Patent Applications

Design patents protect the novel outward appearance of a design, and thus the drawings submitted with a design patent are critical. The patent attorneys and intellectual property professionals at Sierra IP Law, PC are familiar with these requirements and have developed in-house highly skilled drafting talent to provide our clients with high quality renderings of their proprietary designs.