Trademark parodies sit at the intersection of creativity and commerce. From dog toys mimicking famous whiskey bottles to pop songs referencing iconic dolls, parody uses of trademarks can be humorous, but are often legally tricky. When does a playful spoof cross the line into trademark infringement? There is a balance between trademark owners’ rights and free speech, and a fine line between a lawful parody and an infringing use. This article provides an accessible overview of trademark parody examples, the legal framework (including key statutes like the Lanham Act and First Amendment considerations), and highlights major court cases that have shaped the landscape.

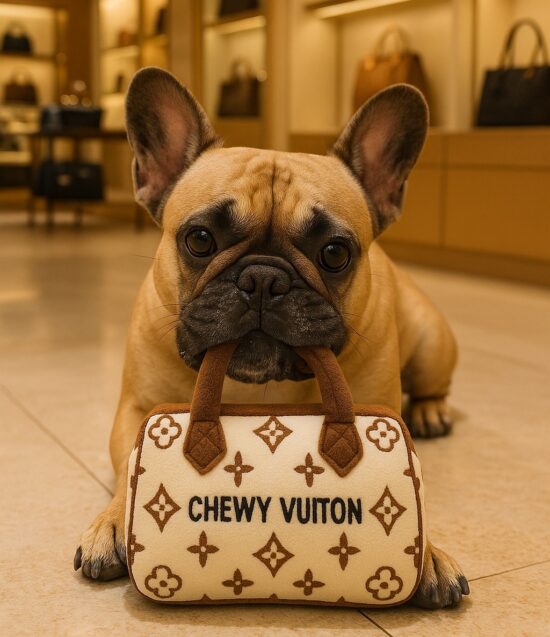

In simple terms, a trademark parody is an unauthorized use of a well-known mark to create a humorous or satirical imitation. The parody juxtaposes an irreverent version of the mark with the original brand’s image. As one court explained, “A parody must convey two simultaneous, and contradictory, messages: that it is the original, but also that it is not the original and is instead a parody”. In other words, a successful parody will remind consumers of the famous mark while also signaling that it is making fun of it. The second message (that “this is a joke”) often involves some obvious difference or exaggeration that adds humor or commentary. For example, naming a dog chew toy “Chewy Vuiton” immediately calls to mind Louis Vuitton luxury handbags, but no one is likely to think a plush dog toy is actually a Louis Vuitton product. The contrast is the source of the joke.

Parodies are often used as social commentary or artistic expression, poking fun at the original work or what it represents. They thrive on the fame of the well-known trademark being mimicked: the bigger the brand, the easier it is for the public to “get” the joke. This means famous brands from fashion, food, entertainment, etc., are frequent targets of parody. While parody can be a form of free speech and protected artistic expression, it also treads on the trademark rights of the brand owner. This inherent tension sets the stage for legal disputes and has prompted courts to develop special rules for parody cases.

Under U.S. law (the Lanham Act), trademark owners have the right to prevent unauthorized use of their marks in a way likely to cause consumer confusion. The classic test for trademark infringement is whether the accused use creates a likelihood of confusion among consumers about the source, sponsorship, or approval of goods. Courts evaluate several factors (the Sleekcraft factors), including similarity of the marks, similarity of the products, strength of the original mark, evidence of actual confusion, and the defendant’s intent. In normal cases, a close imitation of a well-known trademark on similar goods would strongly suggest infringement. Trademark law also protects famous marks from dilution, blurring or tarnishment of their distinctiveness, even without confusion.

Parody complicates this analysis. On one hand, a parody by design uses a mark that is similar to the original, otherwise the joke falls flat. On the other hand, a true parody also deliberately differentiates itself in a way that consumers are not actually tricked into thinking it is the real thing. Thus, courts have recognized that the presence of parody changes how the usual infringement factors are applied. A successful parody can diminish the likelihood of confusion by making the differences (and the humor) obvious. An ineffective parody, however, might just look like a rip-off and still confuse consumers.

When dealing with parody, courts undertake the standard likelihood-of-confusion analysis, but they account for the parody’s nature within that framework. Importantly, parody is not an automatic defense that bypasses the analysis altogether. Instead, parody is a context that can influence certain factors, especially the defendant’s intent and the similarity of the marks in the overall impression. The Fourth Circuit, for example, noted that “an effective parody will actually diminish the likelihood of confusion” because consumers get the joke. Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. Haute Diggity Dog, LLC, 507 F.3d 252 (4th Cir. 2007). They see the contrast between the parody and the original and understand the parodic character of the use.

For confusion to be avoided, the parody should be obvious enough that consumers can tell it’s not the real brand. As the Jack Daniel's Properties Supreme Court decision in 2023 pointed out, a true parody needs to both evoke the original and create contrasts so that the message of humor or ridicule becomes clear. If done well, “a parody is not often likely to create confusion”. Jack Daniel's Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, 599 U.S. 140 (U.S. 2023). Courts will ask: Would the typical consumer of these goods be confused into thinking the brand owner made or endorsed this parody product, or would they recognize it as a joke? In assessing this, factors like the difference in the goods and marketing channels can be crucial. For instance, selling a dog toy in a pet store versus a luxury bag in a designer boutique helped show no confusion in the Chewy Vuiton case, where the name CHEWY VUITON was used in connection with dog toys. By contrast, if a parody uses the mark on the same type of product as the original (e.g. a soft drink parody of another soda brand), the risk of confusion is higher and courts are less forgiving, since consumers might actually think it’s a variant or sub-brand.

Another key factor is the intent of the parody user. While intent to satirize or amuse is legitimate, intent to deceive consumers or trade off the brand’s goodwill is not. As one court put it, the “foremost concern” regarding intent is whether the defendant sought to capitalize on the trademark’s fame in bad faith, or to genuinely make a joke. A parody done in bad faith, for example, a sham “parody” used as a cover for counterfeiting or to confuse consumers, will find little sympathy in court. But when the evidence shows the intent was to create a humorous commentary (and not to trick buyers), that intent weighs against finding trademark infringement.

Aside from confusion-based infringement, trademark dilution is another legal claim that looms over parodies. Dilution law (15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)) protects famous brands from uses that harm their uniqueness or reputation, even if consumers are not confused. Two forms of dilution are recognized: blurring (weakening a mark’s distinctiveness) and tarnishment (harming the mark’s reputation by association with something unsavory). Parodies often raise tarnishment concerns, for example, if a parody makes the brand look ridiculous or vulgar, the brand owner might claim the parody dilutes the brand’s prestige or brand integrity.

However, U.S. law explicitly provides a parody exclusion in dilution cases. The Trademark Dilution Revision Act (TDRA) of 2006 built in a trademark fair use exception for parody and commentary: using a famous mark “other than as a designation of source” for the person’s own goods, to identify and parody, criticize, or comment upon the mark owner or its products, is not actionable as dilution. In plain English, if you are parodying a famous mark in a way that makes clear you’re not pretending your product is that brand, you may avoid liability for dilution.

But crucially, the parody must not be used as the brand for your own goods. If you try to register or claim trademark rights in the parody name itself, effectively treating the parody as your own mark, the dilution exemption likely will not apply. This nuance tripped up the dog toy maker in the Jack Daniel’s case, VIP Products labeled its toy “Bad Spaniels” as part of a product line and sought trademark protection for the name, meaning it was using it as a source indicator. The Supreme Court noted that Congress’s parody exclusion for dilution requires the mark not be used as a designation of source. Because VIP did use the mark to brand its goods, the noncommercial use safe harbor did not automatically shield it from dilution claims.

In practice, parody defendants often argue both no confusion and fair use for dilution. Courts may still scrutinize if the parody tarnishes the brand’s image. After all, not all jokes are appreciated, a parody can be in poor taste and arguably harm the brand’s reputation. For example, in the case of a poster that says “Enjoy Cocaine” in Coca-Cola’s script, the court found that the potential tarnishment of the Coca-Cola brand outweighed the defendant's First Amendment interests. Coca-Cola Co. v. Gemini Rising, Inc., 346 F. Supp. 1183 (E.D.N.Y. 1972).

That said, some judges have observed that a good parody might actually enhance a famous mark’s recognition. In the My Other Bag case (discussed below), the court found the spoof totes likely reinforced Louis Vuitton’s famous image rather than harming it. And even if a brand dislikes being the butt of a joke, that alone does not prove legal harm. Free speech allows commentary that trademark owners may find uncomfortable.

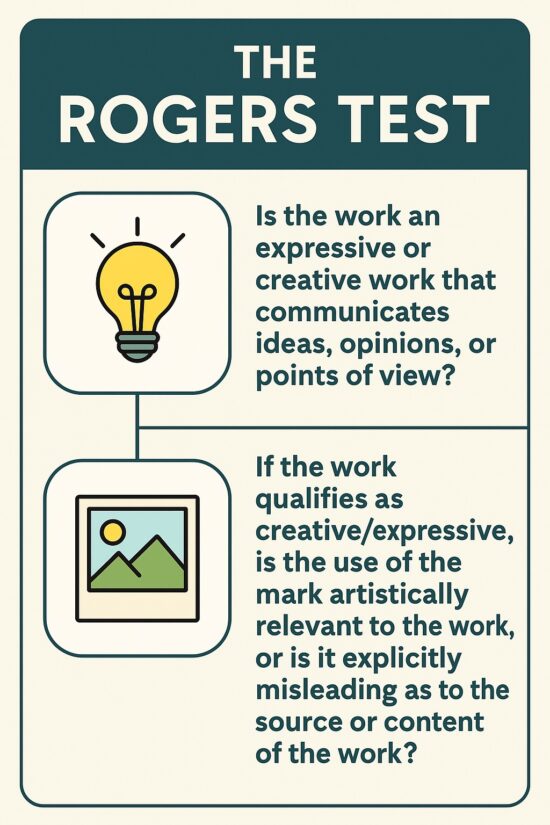

Because trademark enforcement can sometimes clash with free speech, courts have developed a test to protect artistic works that use a trademark in a way that does not indicate association or endorsement. Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1989). The Rogers test basically asks two questions when a trademark is used in an expressive work like a movie, song, or book title:

If the work is expressive or creative, and its use has at least some artistic relevance and does not explicitly mislead consumers into thinking the trademark owner endorsed or produced the work, then the First Amendment interests prevail and no trademark infringement has occurred. This test is meant to give breathing room to creative expression. In the Rogers case, for instance, a film title “Ginger and Fred” referencing Ginger Rogers was allowed because it had artistic relevance and did not explicitly claim Rogers endorsed it.

How does this apply to parody? Many parodies are expressive works, and may be protected by the Rogers test. For example, the “Barbie Girl” pop song by Aqua was a parody and commentary on the Barbie brand and was considered an expressive musical work, rather than a commercial product labeled “Barbie.” The Ninth Circuit applied the Rogers test and concluded that the First Amendment protected the song’s use of “Barbie” because it was artistically relevant to the song’s message and not explicitly misleading about Mattel’s involvement. Mattel v. MCA Records, 296 F.3d 894 (9th Cir. 2002). Mattel’s infringement claims failed, and the court memorably told the parties, “The parties are advised to chill”, underscoring that parody and pop culture commentary are forms of protected speech.

However, the recent 2023 Supreme Court ruling in Jack Daniel’s Properties v. VIP Products clarified that Rogers has limits. The Court unanimously held that Rogers does not apply when someone uses a mark as a trademark, as with the “Bad Spaniels” toy, which was branded like a product. In those cases, the defendant's use of a parody mark is analyzed under the standard infringement analysis with parody treated as a factor in the likelihood of confusion analysis, rather than under the Rogers test. The justices reasoned that trademarks used on commercial goods, even if humorous, are not automatically expressive works akin to artistic titles. They left the Rogers test intact for noncommercial artistic expression, but warned that simply adding a “humorous message” on a product does not trigger a heightened standard in every case. In short, selling a parody dog toy, T-shirt, or other merchandise featuring a spoof of a logo will be treated as a normal trademark use in commerce. The First Amendment protection of the Rogers test is not an absolute.

One of the most notable recent parody cases reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 2023. Jack Daniel’s Properties (the maker of the famous Tennessee whiskey) sued VIP Products LLC over a squeaky dog toy called “Bad Spaniels.” The toy is designed to look like a mini Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle, with similar labeling and trade dress, but altered with humorous treatments of key features of the famous label, including a cartoon spaniel and the phrase “The Old No. 2 on your Tennessee Carpet,” as shown below. VIP made this and other parody products in its “Silly Squeakers” line, mimicking well-known liquor brands as dog toys.

Jack Daniel’s was not amused. The distiller sent a cease and desist letter to stop sales of the toy, and VIP preemptively sued for a declaratory judgment that its toy did not infringe. This kicked off a high-profile legal battle. Initially, a district court sided with Jack Daniel’s, finding trademark infringement and dilution by tarnishment, essentially agreeing that the toy could harm Jack Daniel’s brand by associating it with dog excrement. But on appeal, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals applied the Rogers test finding the toy as an expressive work because it conveyed a humorous message, and ruled for VIP. The Ninth Circuit held that Jack Daniel’s had to satisfy the Rogers threshold test first, which it failed, since “Bad Spaniels” was deemed an expressive, noncommercial use, it was shielded from both infringement and dilution claims.

Jack Daniel’s appealed to the Supreme Court, which resulted in a unanimous decision resetting the rules. The Supreme Court ruled in Jack Daniel’s favor and vacated the Ninth Circuit’s judgment. Justice Elena Kagan, writing for the Court, clarified that when a trademark is used as a trademark (i.e., to identify the source of a product), you do not skip the normal infringement analysis. The humorous nature of the use (“parody or not”) should be considered as part of the standard likelihood-of-confusion test, not as a legal threshold that short-circuits the test. In other words, VIP’s use of Jack Daniel’s trade dress on a product sold in commerce does not get a special First Amendment pass upfront; the case must be decided by asking whether consumers would likely be confused.

The Supreme Court also addressed dilution. The Ninth Circuit had treated the parody as “noncommercial” and thus immune from dilution by tarnishment, but the Supreme Court noted this was incorrect. Congress created a specific parody exclusion in the dilution statute, which only applies if the use is not as a designation of source. VIP’s use failed that condition because it was branding its own goods. Therefore, the dilution claim could proceed, rather than being tossed out as noncommercial speech.

After the Supreme Court’s guidance, the case was sent back down. The key takeaway is that the Supreme Court tightened the leash on the parody defense: parody is not a “safe harbor” against trademark infringement if the parody itself is being used to sell a product in a way that could confuse consumers. However, the Court hinted that a truly successful parody likely would not confuse people: “once the parody’s contrast with the original is clear, confusion is less likely”. The Bad Spaniels story thus highlights the fine line: the toy was funny, but not funny enough to avoid all legal scrutiny. Businesses planning parody-themed goods should note that overt branding of a parody product can undermine their parody defense. It is safer if the parody use is clearly decorative or commentary rather than functioning as a trademark for your own product.

On remand, incidentally, the district court in late 2024 found that Bad Spaniels did not cause confusion but did tarnish the Jack Daniel’s mark, indicating VIP’s parody was recognized as a joke by consumers but still harmed the brand’s reputation. This outcome shows that even a “win” on confusion might not end a parody case where there is also a dilution claim.

Before Bad Spaniels, there was “Chewy Vuiton.” Haute Diggity Dog, a Nevada pet products company, sold plush dog chew toys parodying luxury goods, including a tiny dog toy handbag labeled “Chewy Vuiton,” adorned with similar patterns as a Louis Vuitton purse. Louis Vuitton (LV), the famous French luxury brand, sued for trademark infringement, dilution, and even copyright infringement on the monogram design.

Both the trial court and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the parody maker, Haute Diggity Dog. The courts found that the “Chewy Vuiton” toys were successful parodies of Louis Vuitton’s handbags and marks. In analyzing confusion, the Fourth Circuit noted that LV’s marks are undeniably strong and famous, yet that fame cuts both ways in parody cases. A famous mark is a juicy target for parody, and its fame might actually help consumers realize that a parody is a parody. The court quoted an earlier decision: “In cases of parody, a strong mark’s fame and popularity is precisely the mechanism by which likelihood of confusion is avoided. The parody relies on the fame to make the joke, but its differences (often humorous) make it clear there’s no affiliation.”

In the Chewy Vuiton context, no reasonable buyer would think a plush dog toy (sold for ~$20 in pet stores) is actually a Louis Vuitton handbag. The juxtaposition of the cheap, comical dog toy with the expensive, exclusive image of LV created an unmistakable satire. The toy’s name sounded like Louis Vuitton, but also clearly not identical, and the context screamed “joke”: the product is something for a dog to chew on, whereas if the Louis Vuitton handbag were subject to the same treatment, the owner of handbag would likely be horrified.

Because the parody was obvious, the court ruled there was no likelihood of confusion. In fact, the decision observed that “There are confusing parodies and nonconfusing parodies. ... An effective parody will actually diminish the likelihood of confusion.” Chewy Vuiton was found to be an effective parody, so it reduced any confusion risk. Even though some elements were similar (the monogram pattern, the general look of the design), those were necessary to remind people of LV, but the differences in detail, quality, and presentation differentiated the chew toy. As the court put it, the product “conjures up the famous [Louis Vuitton] marks... but at the same time, it communicates that it is not the LVM product”. Consumers appreciate the point of parody because the contrast is clear.

On the dilution claim, the Fourth Circuit took a slightly different approach than the district court but still found for the defendant. The lower court had said parody meant no dilution. The appeals court clarified that while the district court’s reasoning was off, the result was right. Under the dilution analysis, Chewy Vuiton likely fell under the fair use parody exclusion as a non-source-identifying parody, now codified in 15 U.S.C. §1125(c)(3)(A). And the court even mused that the parody might enhance Louis Vuitton’s brand by reinforcing its fame in a tongue-in-cheek way. Certainly, the evidence did not show that people thought less of the LV mark because of the dog toy joke. So, Louis Vuitton lost on all counts, a well-known early example of the parody serving as a strong defense in trademark law.

The Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC (2023) and Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. Haute Diggity Dog, LLC (2007) cases both involved dog toy parodies of famous luxury brands, but they diverge in both legal treatment and procedural posture. In Chewy Vuiton, the Fourth Circuit treated the parody as an effective and obvious spoof that reduced the likelihood of confusion; consumers “got the joke,” and the toy’s differences and context (pet toy versus luxury handbag) made confusion implausible. The court found that the parody both avoided infringement and qualified for the dilution fair use exclusion because it was not used as a source identifier. By contrast, in Jack Daniel’s, the Supreme Court emphasized that when a mark is used as a source identifier for the parody product itself (i.e., as a trademark), the ordinary likelihood of confusion analysis under the Lanham Act applies, and the defendant cannot automatically invoke First Amendment protections under the Rogers test.

In light of Jack Daniel’s, the outcome of Chewy Vuiton would likely remain the same. The parody in Haute Diggity Dog was not used as a mark to designate the source of a line of products; it was a humorous take on a famous brand, clearly non-confusing, and sold in a distinct market. Even if the traditional likelihood of confusion analysis were applied, the Chewy Vuiton parody would still likely be found non-infringing or diluting, since the Fourth Circuit already found no likelihood of confusion or dilution.

In the late 1990s, the pop group Aqua released “Barbie Girl,” a dance song that playfully mocked the Barbie doll’s image: “I’m a Barbie girl, in a Barbie world, life in plastic, it’s fantastic!”. Mattel, the maker of Barbie, sued MCA Records for trademark infringement and dilution, claiming the song’s use of “Barbie” cast their doll in a bad light: the lyrics call Barbie a “blonde bimbo”. Mattel argued that consumers might think the song was authorized or that Barbie’s brand was tarnished by the adult-themed joke.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, however, firmly sided with the songwriters. The court found Barbie Girl to be a parody or commentary on the Barbie image and thus protected speech. Because this was a song (an artistic work), the court applied the Rogers test for expressive uses. The use of “Barbie” was clearly artistically relevant and nothing about the song explicitly misled listeners to think Mattel produced or endorsed it. In fact, the album had a disclaimer that “The song is a social commentary and was not created or approved by the makers of the doll,” showing lack of intent to confuse. The Ninth Circuit also characterized the use as a type of nominative fair use. Aqua had to use the name “Barbie” to effectively target what they were parodying. The court concluded that trademark law shouldn’t be used to stifle artistic expression or comedic commentary. The First Amendment protection prevailed, and Mattel’s claims were dismissed.

The Barbie Girl case is often cited as a victory for free speech, illustrating that even a famous children’s toy brand cannot suppress a tongue-in-cheek critique of its image. It underscores that when the alleged infringing use is part of an artistic work and not a directly competing product, courts are very reluctant to find trademark infringement. The risk of consumer confusion was practically nonexistent here. No one buying the dance music CD would believe it was actually a Mattel product or officially endorsed. And on the dilution front, the court found the song to be noncommercial use, since it was artistic and not a traditional product advertisement. Thus, Mattel’s tarnishment claims failed as well.

For business owners, Barbie Girl exemplifies that using a trademark in commentary or satire, especially in media like music, art, or literature, has strong First Amendment safeguards. Trademark owners should also note that attempting to litigate in such scenarios may be an uphill battle, and might generate negative PR. Sometimes it is better to “accept the implied compliment in a parody and to smile or laugh than it is to sue” . Louis Vuitton Malletier, S.A. v. My Other Bag , Inc., 156 F. Supp. 3d 425 (S.D.N.Y. 2016).

Louis Vuitton appears again, this time against a small company called My Other Bag (MOB). MOB sold inexpensive canvas tote bags with one side stating “My Other Bag…” and the other side depicting a cartoonish imitation of a luxury handbag. One version showed a design resembling Louis Vuitton’s signature monogram purse with the phrase “...is a Louis Vuitton!” implying the owner’s other bag (tongue-in-cheek) is an LV bag. It is both a pun on the old bumper sticker joke (“My other car is a ___”) and a parody of luxury fashion culture.

LV sued for trademark infringement and dilution, but the courts saw it differently. In a scathing and witty opinion, Judge Jesse Furman of the Southern District of New York held that MOB’s totes are obvious parodies unlikely to confuse consumers and not causing dilution. He reasoned that the totes comment on the very exclusivity and status of Louis Vuitton bags. The differences in product and market were stark: a cheap canvas tote sold for everyday use vs. a pricey designer handbag for upscale use. The judge even noted that a parody like this might reinforce the distinctiveness of LV’s brand by juxtaposing it with a casual alternative. In other words, seeing the joke “My Other Bag is a Louis Vuitton” could remind people how special a real LV is, rather than making it less special.

It is worth noting the difference between parody in trademark law and parody in copyright law. Under U.S. copyright law, parody is a well-established form of fair use. The Supreme Court’s famous Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music case (1994) held that a commercial parody (2 Live Crew’s raunchy parody of “Oh, Pretty Woman”) can qualify as copyright fair use, and that making money from a parody does not disqualify it. The Court emphasized that parody, as a form of commentary or criticism on an original work, is often transformative and can be protected even if done for profit. In other words, the fact that the parody song was sold on an album did not strip it of First Amendment protection in the copyright context. It was protected speech to poke fun at Roy Orbison’s song.

Instead of a blanket defense, trademark parody serves as a possible defense within the standard infringement analysis. The idea is that if the parody is obvious and effective, it will likely mean no consumer confusion and thus no infringement. But if consumers are likely to be confused, then calling something a “parody” will not save it. Additionally, trademark law’s concept of nominative fair use is related but distinct. Nominative fair use allows references to trademarks when necessary to describe or compare, without implying sponsorship. Parody often involves nominative use (you have to refer to the mark you are parodying), but it goes a step further by altering the mark for humor. Courts require that even nominative or parody uses not be misleading about origin or endorsement.

In sum, copyright law gives parodists a stronger shield, whereas trademark parodists must carefully avoid causing confusion. Trademark owners can be more aggressive since any use of their mark by another can be seen as an unauthorized use, but the law tries to accommodate parody as a socially valuable form of expression, within limits.

Trademark parodies occupy a unique space in the legal landscape: they highlight the tension between brand protection and free speech. As we have seen through these examples, U.S. courts do allow room for parody, recognizing that a parody mark or reference, when done well, is a form of artistic and social commentary often deserving First Amendment protection. Key cases (Jack Daniel’s, Haute Diggity Dog, and Barbie Girl) each illustrate how courts analyze parody: is it expressive or just commercial? Does it confuse consumers or make the source of the joke clear? Does it tarnish a famous mark beyond good taste, or simply poke fun in a way the law can tolerate?

A parody that clearly distinguishes itself is often lawful, especially if it is commenting on the original. Conversely, if your “parody” could confuse consumers into thinking the brand is involved, or if it’s simply using the brand’s allure to sell a similar product, there is significant risk of liability. The First Amendment offers robust protection for artistic expression and social commentary, but it will not protect someone trying to use parody of a mark as its own mark or in a manner that does not quite function as a parody.

Going forward, we may see more guidance on how to handle new forms of parody, e.g., internet memes using brand logos, or parodies in the metaverse. But the fundamental lesson remains: parody must have some artistic value and cannot cause consumer confusion or brand dilution.

If you need guidance with respect to parody or other trademark issues, contact our office for a consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney