Trademarks vary in their distinctiveness and ability to uniquely identify a source of goods or services. Some marks are inherently distinctive and can function as trademarks right away. For example, NIKE is a distinctive trademark with respect to athletic wear and shoes because it has no meaning with respect to sportswear and shoes except for the brand identity. Other marks are descriptive of goods or services, such that they are likely to be commonly used in connection with particular goods or services. A mark like DISCOUNT SHOES is descriptive of inexpensive shoes, the goods sold under the mark. Also, many businesses use this phrase to advertise their business, and thus it is not distinctive. Such descriptive, indistinctive marks do not carry enforceable trademark rights when they are adopted to promote a business.

However, a descriptive mark can build meaning in the mind of consumers over time. For example, INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES is a descriptive mark, but because of its longstanding use and investment in advertising and promoting the brand, the INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES mark has acquired distinctiveness in the mind of the consumer. Acquired distinctiveness, also known as secondary meaning, results in enforceable trademark rights in what was once an unenforceable descriptive mark.

A descriptive trademark directly conveys an immediate idea of the qualities, characteristics, purpose, or features of the goods or services it represents. For example, “Creamy Yogurt” for a yogurt product simply describes the texture of the goods and does not inherently distinguish the source. Because descriptive marks do not automatically function as source indicators, they are not registrable on the Principal Register without proof of acquired distinctiveness. In contrast, arbitrary marks use common words in an unrelated context, such as “Apple” for computers, while fanciful marks are invented terms with no prior meaning, like “Xerox” or “Kodak.” Both arbitrary and fanciful marks are considered inherently distinctive, making them eligible for immediate registration and stronger legal protection. Unlike descriptive marks, they do not require evidence of consumer recognition of the source of the goods because their uniqueness alone makes them effective at identifying origin.

Acquired distinctiveness, also known as secondary meaning, is the process by which a descriptive trademark or service mark, initially incapable of registration on the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Principal Register, gains distinctiveness through use in commerce such that it comes to identify a single source in the minds of the consuming public. Under Section 2(f) of the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1052(f)), a mark that is “merely descriptive” may be registered if the applicant can demonstrate that “as a result of substantially exclusive and continuous use,” the mark has “become distinctive of the applicant’s goods [or services] in commerce.”

The legal policy behind the acquired distinctiveness doctrine balances two core interests: (1) protecting consumers from confusion about the source of goods or services and (2) encouraging fair competition by ensuring that common or descriptive terms are not monopolized prematurely. Courts have emphasized that allowing registration of descriptive marks only after secondary meaning is proven ensures that protection is granted only when the mark actually functions as a source indicator. See Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc., 505 U.S. 763, 769 (1992) and Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 U.S. 205, 211 (2000).

The doctrine originates from common law unfair competition principles and was codified in federal trademark law to prevent the unfair appropriation of language necessary for competitors to describe their own goods. It reflects the broader goal of the Trademark Act: protecting consumers and preserving a fair and competitive marketplace. The USPTO Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP) explains that “a mark that is merely descriptive of the goods or services must acquire distinctiveness in order to be registrable on the Principal Register" (TMEP §1212). This acquisition must be demonstrated through evidence showing the primary significance of the mark in the minds of consumers is the producer, not the product or service itself.

Imagine a small bakery business called “Freshmade” that sells artisanal baked goods made daily from scratch. The owner chooses this name because it directly describes the key selling point of the business, daily fresh-baked goods. It’s intuitive, straightforward, and she believes it will appeal to customers looking for homemade-style treats.

At first, the name “Freshmade” helps the business convey exactly what it offers. However, because the name is so descriptive of the nature of the goods, it doesn't stand out from competitors. Several other bakeries in the area use similar phrases like “Fresh Baked Treats” or “Freshly Baked Goods,” which makes it hard for customers to remember or distinguish the brand. As a result, the name doesn’t function well as a source identifier, a key requirement of a trademark. Over time, the owner realizes that despite loyal customers, new customers often confuse her brand with others offering similar products.

When she applies to register “Freshmade” with the USPTO on the Principal Register, the examining attorney issues an Office Action refusing the trademark application under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(1) because the mark is merely descriptive of the goods. The USPTO notes that the phrase simply describes a feature or characteristic of the cookies, rather than serving as a unique brand name. She has only been in business for two years and she does not have a strong basis for demonstrating that the mark has acquired distinctiveness.

Because she cannot show that consumers associate the phrase “Freshmade” specifically with her business, her application is ultimately refused. She may still register the mark on the Supplemental Register, but this does not provide the same legal benefits or presumptions of validity as registration on the Principal Register.

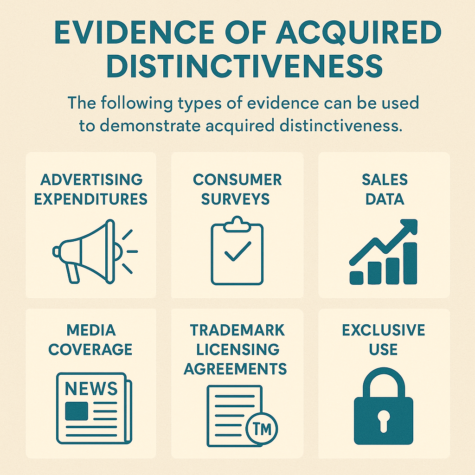

In scenarios like the Freshmade story above, the trademark owner may seek registration on the Principal Register once the trademark use meets certain requirements. A trademark applicant can make a claim of acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f) if there is sufficiently extensive use and/or other evidence that the trademark has acquired distinctiveness in the minds of the relevant consumers. To prove that a descriptive mark has acquired distinctiveness, applicants can provide various forms of evidence:

If the applicant owns one or more prior registrations of the same mark on the Principal Register for similar goods or services, this can serve as prima facie evidence of distinctiveness. However, the prior registration must be in full force and not expired or canceled.

A declaration stating that the mark has been in substantially exclusive and continuous use in commerce for at least five years preceding the date of the claim can support acquired distinctiveness. It is important to note that mere use of the mark is insufficient. The use must be exclusive and continuous.

This includes a variety of materials for proving acquired distinctiveness:

Claiming acquired distinctiveness presents a significant evidentiary burden for the applicant, particularly when the mark in question is weak or widely used. The standard is especially high for highly descriptive marks, which directly convey characteristics, ingredients, or qualities of the goods or services. Such marks require robust, persuasive evidence to establish that the primary significance of the mark in the minds of consumers is to identify the source rather than the product itself. The challenge is further compounded when the mark is commonly used by others in the same industry. If third parties are using similar terms to describe their products or services, it weakens the applicant’s argument that the mark is perceived as distinctive or uniquely associated with their brand. Additionally, limited advertising or promotion can make it difficult to demonstrate the necessary level of consumer recognition or association with a single source. In In re Yarnell Ice Cream, LLC, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) rejected a claim of acquired distinctiveness for the mark “SCOOP” for ice cream, finding it highly descriptive and noting that the applicant failed to present sufficient evidence of secondary meaning, despite five years of use and some media coverage.

Securing trademark protection is vital for brand identity and legal rights. Understanding the difference between descriptive marks and more distinctive mark can prevent issues with the trademark application process and trademark enforcement. However, it is common for businesses to adopt descriptive marks for various business reasons. In such cases, evidence of acquired distinctiveness may be utilized to acquire a trademark registration and to establish enforceable trademark rights in court.

If you need assistance with trademark selection, vetting, registration, or other trademark matters, please contact us for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney