Trademarks vary in their distinctiveness and ability to uniquely identify a source of goods or services. Some marks are inherently distinctive and can function as trademarks right away. For example, NIKE is a distinctive trademark with respect to athletic wear and shoes because it has no meaning with respect to sportswear and shoes except for the brand identity. Other marks are descriptive of goods or services, such that they are likely to be commonly used in connection with particular goods or services. A mark like DISCOUNT SHOES is descriptive of inexpensive shoes, the goods sold under the mark. Also, many businesses use this phrase to advertise their business, and thus it is not distinctive. Such descriptive, indistinctive marks do not carry enforceable trademark rights when they are adopted to promote a business.

However, a descriptive mark can build meaning in the mind of consumers over time. For example, INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES is a descriptive mark, but because of its longstanding use and investment in advertising and promoting the brand, the INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES mark has acquired distinctiveness in the mind of the consumer. Acquired distinctiveness, also known as secondary meaning, results in enforceable trademark rights in what was once an unenforceable descriptive mark.

A descriptive trademark directly conveys an immediate idea of the qualities, characteristics, purpose, or features of the goods or services it represents. For example, “Creamy Yogurt” for a yogurt product simply describes the texture of the goods and does not inherently distinguish the source. Because descriptive marks do not automatically function as source indicators, they are not registrable on the Principal Register without proof of acquired distinctiveness. In contrast, arbitrary marks use common words in an unrelated context, such as “Apple” for computers, while fanciful marks are invented terms with no prior meaning, like “Xerox” or “Kodak.” Both arbitrary and fanciful marks are considered inherently distinctive, making them eligible for immediate registration and stronger legal protection. Unlike descriptive marks, they do not require evidence of consumer recognition of the source of the goods because their uniqueness alone makes them effective at identifying origin.

Acquired distinctiveness, also known as secondary meaning, is the process by which a descriptive trademark or service mark, initially incapable of registration on the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Principal Register, gains distinctiveness through use in commerce such that it comes to identify a single source in the minds of the consuming public. Under Section 2(f) of the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1052(f)), a mark that is “merely descriptive” may be registered if the applicant can demonstrate that “as a result of substantially exclusive and continuous use,” the mark has “become distinctive of the applicant’s goods [or services] in commerce.”

The legal policy behind the acquired distinctiveness doctrine balances two core interests: (1) protecting consumers from confusion about the source of goods or services and (2) encouraging fair competition by ensuring that common or descriptive terms are not monopolized prematurely. Courts have emphasized that allowing registration of descriptive marks only after secondary meaning is proven ensures that protection is granted only when the mark actually functions as a source indicator. See Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc., 505 U.S. 763, 769 (1992) and Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 U.S. 205, 211 (2000).

The doctrine originates from common law unfair competition principles and was codified in federal trademark law to prevent the unfair appropriation of language necessary for competitors to describe their own goods. It reflects the broader goal of the Trademark Act: protecting consumers and preserving a fair and competitive marketplace. The USPTO Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP) explains that “a mark that is merely descriptive of the goods or services must acquire distinctiveness in order to be registrable on the Principal Register" (TMEP §1212). This acquisition must be demonstrated through evidence showing the primary significance of the mark in the minds of consumers is the producer, not the product or service itself.

Imagine a small bakery business called “Freshmade” that sells artisanal baked goods made daily from scratch. The owner chooses this name because it directly describes the key selling point of the business, daily fresh-baked goods. It’s intuitive, straightforward, and she believes it will appeal to customers looking for homemade-style treats.

At first, the name “Freshmade” helps the business convey exactly what it offers. However, because the name is so descriptive of the nature of the goods, it doesn't stand out from competitors. Several other bakeries in the area use similar phrases like “Fresh Baked Treats” or “Freshly Baked Goods,” which makes it hard for customers to remember or distinguish the brand. As a result, the name doesn’t function well as a source identifier, a key requirement of a trademark. Over time, the owner realizes that despite loyal customers, new customers often confuse her brand with others offering similar products.

When she applies to register “Freshmade” with the USPTO on the Principal Register, the examining attorney issues an Office Action refusing the trademark application under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(1) because the mark is merely descriptive of the goods. The USPTO notes that the phrase simply describes a feature or characteristic of the cookies, rather than serving as a unique brand name. She has only been in business for two years and she does not have a strong basis for demonstrating that the mark has acquired distinctiveness.

Because she cannot show that consumers associate the phrase “Freshmade” specifically with her business, her application is ultimately refused. She may still register the mark on the Supplemental Register, but this does not provide the same legal benefits or presumptions of validity as registration on the Principal Register.

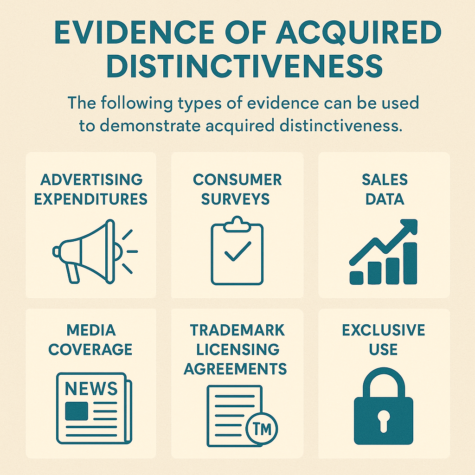

In scenarios like the Freshmade story above, the trademark owner may seek registration on the Principal Register once the trademark use meets certain requirements. A trademark applicant can make a claim of acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f) if there is sufficiently extensive use and/or other evidence that the trademark has acquired distinctiveness in the minds of the relevant consumers. To prove that a descriptive mark has acquired distinctiveness, applicants can provide various forms of evidence:

If the applicant owns one or more prior registrations of the same mark on the Principal Register for similar goods or services, this can serve as prima facie evidence of distinctiveness. However, the prior registration must be in full force and not expired or canceled.

A declaration stating that the mark has been in substantially exclusive and continuous use in commerce for at least five years preceding the date of the claim can support acquired distinctiveness. It is important to note that mere use of the mark is insufficient. The use must be exclusive and continuous.

This includes a variety of materials for proving acquired distinctiveness:

Claiming acquired distinctiveness presents a significant evidentiary burden for the applicant, particularly when the mark in question is weak or widely used. The standard is especially high for highly descriptive marks, which directly convey characteristics, ingredients, or qualities of the goods or services. Such marks require robust, persuasive evidence to establish that the primary significance of the mark in the minds of consumers is to identify the source rather than the product itself. The challenge is further compounded when the mark is commonly used by others in the same industry. If third parties are using similar terms to describe their products or services, it weakens the applicant’s argument that the mark is perceived as distinctive or uniquely associated with their brand. Additionally, limited advertising or promotion can make it difficult to demonstrate the necessary level of consumer recognition or association with a single source. In In re Yarnell Ice Cream, LLC, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) rejected a claim of acquired distinctiveness for the mark “SCOOP” for ice cream, finding it highly descriptive and noting that the applicant failed to present sufficient evidence of secondary meaning, despite five years of use and some media coverage.

Securing trademark protection is vital for brand identity and legal rights. Understanding the difference between descriptive marks and more distinctive mark can prevent issues with the trademark application process and trademark enforcement. However, it is common for businesses to adopt descriptive marks for various business reasons. In such cases, evidence of acquired distinctiveness may be utilized to acquire a trademark registration and to establish enforceable trademark rights in court.

If you need assistance with trademark selection, vetting, registration, or other trademark matters, please contact us for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

It is generally known that patents allow the owner exclusive rights to exploit an innovation. However, the period of that protection is limited. There is a basic quid pro quo that underlies US patent law: if you develop a new and useful invention, you can have exclusive rights to that invention for a defined time period, but then it enters the public domain and anyone can use it to their benefit. Many people do not understand this bargain or that the patented technology is free to use after a patent expires. Entrepreneurs and technologists can analyze expired patents to adopt, adapt, or build upon the underlying invention without paying licensing fees.

Lapsed patents work differently. A utility patent can lapse due to a failure to pay required patent maintenance fees. The public can lawfully use the technology in a lapsed patent. However, if the patent lapsed due to inadvertent failure to pay the maintenance fees, the patent owner may later revive the patent. Thus, practicing the invention of a lapsed patent carries some risk and should be considered with the guidance of a skilled patent attorney.

In this article, we discuss legal framework of expired and lapsed patents and the legal issues related to utilizing the formerly patented technology.

When a patent expires, the exclusive rights granted to the patent owner, including the right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the invention, come to an end. At that point, the intellectual property becomes part of the public domain, and anyone can use it without fear of infringement.

Uninformed entrepreneurs (e.g., inventors, small businesses, etc.) may miss out on valuable opportunities by overlooking the benefits of using expired patents. For example, if a consumer electronics patent from 20 years ago has expired, you may be able to use its original invention as a foundation for further innovation, saving time and R&D costs.

In the United States, patents are governed by federal patent law and administered through the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The USPTO has a public patent database of all issued patents that allows anyone to find patented technology relevant to their business or field. You can search by keyword, inventor name, patent number, assignee, or filing date. Once you locate a patent, PDF or image files of the patent are viewable. To determine whether the patent has expired, you can look at the filing date, issue (grant) date, and the type of patent (utility, design, or plant) on the first page of the patent. For utility patents filed after June 8, 1995, the term is generally 20 years from the filing date. However, there are some nuances to determining the filing date.

Accurately identifying the effective filing date is required to determine the patent's term and expiration date. To determine the effective filing date of a utility patent from the first page of the patent document, which includes various data sections identified by Internationally Agreed Numbers for the Identification of Data (INID codes), found in parentheses on the left side of each column. If the patent was the result of a single application with no claims to prior filed provisional or parent applications, the patent term will be determined based on the filing date of the application. The “Filed” field (22) found in the first column of the first page provides the date on which the application was filed. However, if the patent claims benefit of an earlier non-provisional patent application (e.g., a parent application), the effective filing date will be the date of the earliest validly claimed non-provisional patent application listed in the “Related U.S. Application Data” section (63).

If a patent claims priority to any prior non-provisional patent filings, the “Related U.S. Application Data” section lists the any continuation, continuations-in-part, and/or divisional priority claims, along with the corresponding filing dates. The effective filing date is the earliest date on which the subject matter claimed in the patent was first disclosed in an earlier non-provisional patent application to which the patent validly claims priority.

When a patent lists only priority claims to divisional and/or continuation patents in the “Related U.S. Application Data” section, the effective filing date is generally the earliest filing date in that chain (see the image below), assuming the claims are fully supported by the original disclosure. If the list includes a priority claim to a continuation-in-part (CIP), the effective filing date for each claim depends on whether it is supported by the earlier application. Claims supported by the original parent application (earliest filed non-provisional) retain the parent’s date; new matter introduced in the CIP gets the CIP’s filing date. Determining the correct date may require reviewing the specifications of all listed applications.

Section (60) identifies any priority claims to provisional patent applications. However, these priority claims do not impact the 20 year patent term. They are irrelevant to determining when the patent expiration date.

Foreign priority claims under 35 U.S.C. § 119 do not affect the patent term in the United States. While they establish an earlier priority date for determining novelty and non-obviousness, the patent term is still calculated from the actual U.S. filing date of the non-provisional application, not the foreign priority date. Foreign priority can strengthen patent validity by reducing the amount of available prior art, it does not shorten or extend the statutory patent term in the U.S.

Any Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) or Patent Term Extension (PTE) granted for a patent is typically noted in the “Notice” section on the first page of the issued patent. However, these two extensions arise under different statutes, serve different purposes, and apply under different circumstances.

Patent Term Adjustment, governed by 35 U.S.C. § 154(b), compensates for delays caused by the USPTO during prosecution. This includes delays such as extended examination, failure to meet response deadlines, or time spent in appeal. The adjustment is automatically calculated and expressed as a number of days added to the standard 20-year term from the earliest effective filing date of a utility patent. PTA applies only to utility patents, not design or plant patents.

Patent Term Extension (PTE) is granted under 35 U.S.C. § 156 and applies to patents covering products subject to regulatory review, such as pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and agricultural chemicals. PTE compensates for the time lost while waiting for FDA or other regulatory approval before a product can be marketed. PTE is granted upon request, and if awarded, the extension is noted on the face of the patent, often with language such as “180-day patent term extension granted.”

Both PTA and PTE extend the enforceable life of the patent beyond the standard term, but they are based on different causes of delay, administrative delays for PTA and regulatory delays for PTE, and are authorized by separate statutory provisions.

A terminal disclaimer is a legal statement filed with the USPTO in which a patent applicant agrees to limit the term of a later-filed patent so it expires no later than an earlier related patent, often in the same patent family. This is typically done to overcome a non-statutory double patenting rejection, where two patents claim obvious variations of the same underlying invention. The terminal disclaimer ensures that the public does not suffer from extended patent protection for obvious variants of the same invention.

Terminal disclaimers affect the patent’s term by cutting it short, aligning its expiration with the earlier patent's expiration date. Importantly, terminal disclaimers also require that the patents remain commonly owned. If ownership is later divided, the disclaimed patent may become unenforceable.

This principle was confirmed in In re Hubbell, 709 F.3d 1140 (Fed. Cir. 2013), where the Federal Circuit upheld the requirement for common ownership of patents subject to a terminal disclaimer. The court emphasized that separating ownership undermines the basis for the disclaimer, preventing unjustified time extensions of exclusive rights. Thus, a patent holder should carefully manage licensing agreements and assignments in families with terminal disclaimers to avoid unenforceability of valuable patent assets.

The patent term of a U.S. national stage application filed under 35 U.S.C. § 371, based on an international Patent Cooperation Treaty application (PCT), is generally 20 years from the international filing date of the PCT application, not the date of national stage entry. The same term calculation is applied to national stage applications as to regular U.S. utility applications using the PCT application date as the priority date. Therefore, even if national stage entry occurs up to 30 months later, the 20-year term still begins from the PCT’s international filing date. If the PCT application claims priority to an earlier foreign patent application under 35 U.S.C. § 119, that foreign priority date does not affect the term, it only affects patentability. Additionally, PTA and PTE are applicable and may extend the term.

Determining a patent’s expiration requires careful consideration of its priority dates, any patent term extensions (PTEs), and the presence of terminal disclaimers. The priority date, often the earliest effective filing date listed in the “Related U.S. Application Data” section, establishes the starting point for calculating the standard 20-year term for utility patents. Any granted PTE adds days to this term to compensate for USPTO or regulatory delays. However, a terminal disclaimer can override the calculated term by shortening it to match the expiration of an earlier related patent. When a terminal disclaimer is present, determining the correct expiration date may require reviewing the file wrapper (the patent’s prosecution history) to identify the prior patent to which the disclaimer is tied and whether that earlier patent remains enforceable. Without this context, expiration dates on the face of the patent may be misleading. Therefore, analyzing all of these elements together is essential for accurately assessing a patent’s term.

Although patents are granted for a specific term, they can expire early or lapse for a variety of reasons. Understanding the different pathways to expiration is essential for entrepreneurs that plan to use, license, or build upon a technology patented by someone else, and for the patent holder themselves. Misinterpreting a patent’s status can lead to legal risks or missed opportunities for either kind of party. Below are several common scenarios that may lead to early expiration or lapse of intellectual property rights.

A patent naturally expires when it reaches the end of its statutory term, which is typically 20 years from the earliest effective filing date. Once this term expires, the patent owner no longer has the exclusive rights to prevent others from making, using, or selling the invention. At that point, the patented technology enters the public domain, where it may be freely used by competitors and the public. Natural expiration is the most straightforward method by which a patent ends. However, it is quite common for the filing and prosecution history of the patent to be more complicated. In such circumstances, close attention must be paid to filing dates, patent term extensions, and other factors to calculate accurately. Businesses analyzing expired patents should always verify the correct term based on the type of patent and applicable rules.

For utility patents, the patent office requires the patent holder to pay maintenance fees at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after the patent is granted. Failure to make timely payments causes the patent to lapse and become unenforceable. However, the USPTO provides a six-month grace period during which the patent owner can reinstate the patent by paying the overdue fee along with a surcharge. If the owner fails to take action within that time, the patent will be considered lapsed. However, even if a patent lapses, it may still be reinstated under certain conditions, which can complicate determinations of enforceability. If the patent lapsed due to inadvertent error, it can be revived. Businesses considering use of lapsed patents should consult with patent attorneys to assess the risk that the patent holder will revive the patent and whether intervening rights may apply to safeguard their activities.

A terminal disclaimer is filed to overcome a non-statutory double patenting rejection by aligning the term of one patent with that of an earlier related patent in the same family. When this occurs, the disclaimed patent will expire no later than the earlier patent’s expiration date, even if it would otherwise qualify for a longer term. This can significantly shorten the duration of patent protection. Terminal disclaimers also require that both patents remain commonly owned for enforceability. If the patents become separately owned through sale, transfer, or licensing, the disclaimed patent may become unenforceable, as clarified by Federal Circuit case law such as In re Hubbell. To accurately determine expiration, especially in complex families, it may be necessary to review the file wrapper and identify which patent the terminal disclaimer references. Overlooking a terminal disclaimer can result in relying on a patent that has already expired.

A patent can also cease to be enforceable through judicial invalidation. U.S. federal courts, including the Supreme Court, may declare a patent invalid or unenforceable for several reasons, including lack of novelty, obviousness, failure to meet written description requirements, or inequitable conduct during prosecution. When a patent is invalidated by court ruling, it is as if the legal right never existed. This outcome applies retroactively and can affect licensing agreements, infringement lawsuits, and business strategies built around the patent. Companies relying on active patents, especially in competitive fields like consumer electronics, pharmaceutical patents, and power systems, should stay informed about relevant litigation that may impact the enforceability of key patent assets. It is important to note that a patent listed as active in the USPTO database may still have been nullified by court action, so legal status checks should always include a litigation search.

In rare but impactful cases, changes in patent law or regulatory exclusivity rules can affect whether a patent remains enforceable or how long its term lasts. This is particularly relevant to pharmaceutical patents and biologics, where legislation such as the Hatch-Waxman Act or the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) may shorten or extend effective exclusivity periods. Additionally, international treaties and domestic reforms may alter how patent terms are calculated or whether international protection is available. Some reforms have introduced patent term adjustments (PTAs) or eliminated extensions under certain circumstances. Businesses should monitor legislative developments to assess how they might impact patent strategy, particularly for products reliant on extended exclusivity for market entry or licensing revenue. Consulting with experienced patent attorneys is critical to understanding how evolving rules may affect the enforceability or term of a particular patent portfolio.

Once a patent expires, it enters the public domain, meaning the exclusive rights previously held by the patent owner no longer apply. For large and small businesses alike, this opens the door to using the underlying invention for product development, manufacturing processes, or commercialization without needing a license or worrying about infringement claims. Expired patents serve as a rich source of technical knowledge and proven designs, making them valuable tools for businesses looking to further innovation with reduced legal risk and lower R&D investment.

The expiration of a patent is in the public domain: anyone is legally free to use, make, sell, or improve upon the previously protected invention without obtaining permission or paying licensing fees. This allows new market entrants to build upon old patents, especially in industries like consumer electronics, manufacturing, and pharmaceuticals. For instance, when pharmaceutical patents expire, generic manufacturers can produce equivalent drugs at lower costs, often resulting in increased accessibility for consumers and new business opportunities for manufacturers. In other industries, expired patents can form the basis for product lines, reduce development timelines, or inspire entirely new solutions. Reviewing and analyzing expired patents can give businesses a competitive edge while fostering innovation.

Lapsed patents may not be permanently unenforceable. In some cases, a patent holder can reinstate a lapsed utility patent by paying overdue maintenance fees within the USPTO’s six-month grace period. In limited circumstances, reinstatement may also be granted beyond that period through a successful petition showing that the lapse was unintentional. When a patent is reinstated, it regains enforceability, but not without consequences for third parties.

If a business began using the invention during the lapse in good faith, it may acquire intervening rights under patent law. These rights can shield the user from infringement liability, particularly for products made, purchased, or developed while the patent was unenforceable.

Intervening rights are statutory defenses available to third parties who, in good faith, begin using, making, or selling a patented invention during a period when the patent is unenforceable, such as after lapse due to nonpayment of maintenance fees or after a substantial amendment to claims in a reissue or reexamination proceeding. These rights are codified in 35 U.S.C. § 41(c). While often discussed in the context of post-grant proceedings, courts have extended these principles to lapsed and later-reinstated patents.

There are two categories of intervening rights:

Absolute rights allow a third party to continue using or selling specific products that were made, purchased, or contracted for before the patent was reinstated. These rights are not discretionary, they are granted as a matter of law if the activity was initiated in reliance on the patent’s lapse.

Equitable rights give courts discretion to permit continued activity, potentially including expansion of use, based on fairness and the extent of investment or reliance made during the lapse. Courts weigh factors such as the nature of investments, duration of use, and knowledge of the original patent.

Courts may apply equitable doctrines, including estoppel and reliance-based protections, to shield third parties who acted in good faith during the lapse. Therefore, while § 41(c) permits reinstatement, it does not erase the legal significance of a period during which the patent was unenforceable. Businesses relying on such a lapse should consult with patent attorneys to assess whether they have a viable intervening rights defense if the patent is later reinstated.

The term of a patent also varies depending on the type of patent granted. Utility patents, which cover new and useful processes, machines, or compositions of matter, generally last 20 years from the earliest effective filing date under 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2).

In contrast, plant patents, which protect asexually reproduced plant varieties, also have a 20-year term, but unlike utility patents, no maintenance fees are required to keep them in force. Thus, there is no opportunity for lapsed plant patent.

Design patents, which protect the ornamental design of a functional item, have a different term entirely. For applications filed on or after May 13, 2015, the term is 15 years from the grant date under 35 U.S.C. § 173, and likewise require no maintenance fees. Understanding these differences is essential when evaluating a patent’s duration.

When a patent expires, it opens the door for use of the patented technology and further innovation, allowing others to use, build upon, and earn money from the original invention without needing to negotiate licensing agreements. However, it’s crucial to accurately determine the patent expiration date. Missteps can lead to costly litigation or lost opportunities.

By working with patent attorneys, you can analyze expired patents in your field, stay ahead of your competitors, and turn intellectual property rights once held by others into growth opportunities for your business.

To learn more or get help with evaluating expired patents, contact us for a consultation with an experienced patent attorney.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

When launching a new product, service, or business, you should create a brand around it and protect that brand. It is a worthwhile exercise to familiarize yourself with the different types of trademarks available under trademark law. Whether you're naming a new streaming service, labeling an actual product, or identifying your business name, selecting the right kind of trademark is key to securing brand protection and avoiding infringement.

This guide breaks down the main types of trademarks, using accessible language for entrepreneurs and small business owners unfamiliar with legal jargon. By the end, you’ll understand how to choose an appropriate mark for your brand, avoiding problematic marks such as generic terms. We also provide a brief discussion of the trademark registration process with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

A trademark is a word, phrase, symbol, or design, or any combination of those things that identifies and distinguishes the source of the goods from other sources of goods. In other words, a trademark distinguishes one provider of goods from another (e.g., Coach from Louis Vuitton). Think of a trademark as your brand’s signature. It helps customers recognize your company and its offerings.

Under U.S. trademark law, trademarks can be words, letters, logos, or even non-traditional marks like sounds, colors, or smells. They must be distinctive enough to differentiate your specific brand from others in the marketplace.

Service marks are essentially the same as trademarks, except that service marks are used in connection with services rather than goods. For example, the Federal Express company does not sell goods, it sells package delivery services in connection with the FedEx® mark. Thus, the FedEx® mark is a service mark.

Not all marks are created equal. The more distinctive a trademark is, the stronger the legal protection it provides. Trademark law recognizes a spectrum of distinctiveness that determines the strength of a mark and the level of protection it provides. The more distinctive a mark is, the more protection it receives. Let’s look at the five primary categories:

Fanciful trademarks are completely invented or coined terms with no prior meaning in any language. These are not real words until a business or organization creates and uses them as a mark. Because they have no preexisting definition or association with a type of product, service, or industry, fanciful marks are considered the strongest type of trademark under U.S. law. This category is also referred to as “coined marks” or “invented words.”

Fanciful trademarks are inherently distinctive, which means they are eligible for registration and legal protection without the need to prove acquired distinctiveness. Acquired distinctiveness is secondary meaning that is established in the mind of the consumer over time through advertising under the trademark and presence in the marketplace. The inherent distinctiveness of fanciful marks makes it much easier to enforce trademark rights against infringing third parties.

Well-known examples of fanciful trademarks include Kodak®, Xerox®, Exxon®, and Verizon®. None of these words existed before they were adopted by companies to identify their goods or services. Today, these names are strongly associated with a single source of goods or services, providing clear and powerful brand recognition.

Fanciful marks receive the highest level of protection. They are typically not vulnerable to claims of descriptiveness, nor are they likely to be confused with other existing marks, given their uniqueness. This makes them ideal candidates for federal registration and long-term legal protection.

Businesses that want to create a memorable and legally defensible brand should strongly consider a fanciful trademark. While such marks may initially require more effort and marketing to build consumer recognition, the long-term benefits in terms of exclusivity, trademark protection, and market clarity are substantial.

Arbitrary trademarks consist of real, commonly known words that are used in a way entirely unrelated to their ordinary meaning. Unlike fanciful trademarks—which are completely invented—arbitrary marks take existing dictionary words and apply them to goods or services with which they have no logical or descriptive connection. This disconnect between the mark’s usual definition and the product it represents makes the mark distinctive and highly protectable.

Arbitrary trademarks are also considered inherently distinctive, placing them near the top of the trademark protection hierarchy. They are eligible for federal registration with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and do not require a showing of acquired distinctiveness. This makes them highly valuable in terms of both legal enforceability and brand positioning.

The effectiveness of arbitrary marks lies in the unexpected pairing of a familiar word with an unrelated product or service. This counterintuitive use creates a memorable brand that avoids being descriptive or generic, both of which receive less protection under trademark law. The more unrelated the word is to the actual product or service, the stronger the trademark rights, and the more defensible the mark is against competitors.

Some of the most famous arbitrary trademarks include Apple® for computers and Amazon® for online retail. In both cases, the words have clear meanings in the English language. “Apple” is a fruit, and “Amazon” is a river and rainforest region. However, neither word describes or suggests anything about technology or e-commerce. The selection of these common terms for unrelated industries results in strong brand identifiers that are easily distinguishable from others in the marketplace.

Companies seeking a bold, recognizable, and enforceable identity without inventing a new word may benefit from choosing an arbitrary mark.

Suggestive marks are terms that indirectly hint at the characteristics, qualities, or purpose of a product or service, but do not directly describe them. These marks require consumers to use imagination, thought, or perception to connect the name to the underlying goods or services. Because they imply rather than describe, suggestive marks occupy a middle ground in the spectrum of distinctiveness recognized by trademark law.

Suggestive trademarks are considered inherently distinctive, which means they can be registered with the USPTO without needing to prove secondary meaning. While they are slightly weaker than fanciful or arbitrary marks in terms of distinctiveness, they are still strong from a trademark protection standpoint and enjoy full legal protection once registered.

The success of suggestive marks lies in their ability to convey a benefit, feeling, or association without using generic or descriptive terms. This subtlety allows a business to build a compelling brand identity that resonates with customers, while still qualifying for intellectual property protection. Suggestive marks also strike a balance between marketing effectiveness and legal strength, making them appealing to many small businesses.

Suggestive trademarks are often seen as more creative or clever than descriptive ones, allowing companies to hint at other characteristics or benefits of their offerings without limiting future brand expansion.

One classic example is Netflix®, which subtly suggests “internet” and “flicks” (movies), but doesn’t literally describe a streaming service. Another is Coppertone®, which evokes the sun-kissed, coppery glow of suntanned skin but doesn't directly state “suntan lotion.” These marks function well because they are both evocative and legally protectable, without straying into descriptive marks territory.

Descriptive trademarks are terms that directly describe a feature, quality, characteristic, function, or purpose of the underlying product or service. These are known as descriptive marks, and they convey information that a consumer might use to evaluate the product, such as what it is, what it does, or a key ingredient or benefit. Because of this clarity, they may seem appealing from a marketing standpoint, but from a legal perspective, they face serious limitations.

Descriptive marks receive low legal protection, especially at the outset. The USPTO often refuses registration of such marks unless the applicant can prove that the mark has acquired secondary meaning in the minds of customers.

To gain protection, the trademark owner must show that consumers associate the descriptive term with a specific brand or trademark holder, rather than with the product category generally. This can be demonstrated through long-standing use, significant advertising expenditures, customer surveys, or strong market presence. Once secondary meaning is established, the mark becomes eligible for trademark registration.

Many descriptive marks are initially rejected by the USPTO, and unless the applicant can present compelling evidence of secondary meaning, the application will be rejected.

Marks like American Airlines® for air travel services in the US or Quick Print® for printing services fall squarely into this category. They tell the consumer exactly what to expect: something cold and creamy (ice cream), or fast printing (printing services). However, because they describe the goods rather than serve as unique identifiers, they lack the inherent distinctiveness required for immediate trademark protection.

Avoid descriptive trademarks when possible, opt instead for suggestive, arbitrary, or fanciful marks for stronger and easier-to-enforce trademark rights.

Generic trademarks, more accurately referred to as generic terms or generic marks, are common words or phrases that name a general class or category of products or services. These terms are the everyday language that consumers use to refer to goods, such as “bread,” “bicycle,” or “computer.” Because they are not distinctive and simply describe what the product or service is, they cannot function as trademarks under U.S. law.

Generic marks have no legal protection. The USPTO will deny any application that uses generic terminology to describe the goods or services. Likewise, courts will not enforce a generic term, as doing so would unfairly restrict competitors from accurately describing their own offerings.

Examples of generic marks include using the word “Computer” for a line of computers or “Milk” for a brand of dairy products. These terms tell the consumer what the product is, but not who is providing it. As a result, they fail to identify a unique source of goods or services and are not capable of being registered or enforced as trademarks.

Perhaps the most significant danger with generic terms is the risk of genericide, when a once-protectable trademark becomes so widely used as the name for a product category that it loses its distinctiveness. Famous examples include “Aspirin,” “Escalator,” and “Cellophane.” These marks were once registered and enforced, but over time, customers began using them to refer to the general product, not the specific brand. As a result, they lost their trademark rights.

Avoid using generic terms as trademarks, even if they are easy to market. Instead, choose a name that is distinctive, creative, and uniquely identifies your goods or services, one that provides real legal protection and helps your business stand out.

Beyond the basic spectrum of distinctiveness, there are additional categories recognized by the USPTO that serve unique functions.

Certification marks are a unique category of trademark used to indicate that goods or services meet specific standards established by a certifying organization. These standards can relate to quality, safety, origin, manufacturing methods, labor practices, or other measurable attributes. Unlike traditional trademarks, a certification mark is not used by the owner to promote their own goods or services, but rather by others who meet certain standards. For example, UL® (Underwriters Laboratories) certifies that products meet safety standards. The certifying entity sets the rules and authorizes the use of the mark by qualifying parties. Certification marks serve as indicators of trustworthiness and compliance, helping customers identify products that have been independently verified against established benchmarks. Because of their role in consumer protection and market integrity, certification marks receive trademark protection under U.S. trademark law, provided the certifier remains neutral and maintains control over usage.

Collective marks are a specialized type of trademark used to identify members of a collective group or association, such as a professional organization, trade union, cooperative, or other collective group. The primary purpose of a collective mark is to indicate that the person or business using the mark belongs to a specific group that adheres to certain membership standards or ethical guidelines. A well-known example is REALTOR®, which is used exclusively by members of the National Association of Realtors. The mark itself is owned by the collective organization, not the individual members, and use is governed by strict rules set by the organization. When a member uses the mark, it signals affiliation with the group and often implies adherence to a shared code of conduct or qualifications. Collective marks are especially useful for industries where membership in a regulated or respected group adds value, trust, or credibility in the eyes of customers or the public.

Non-traditional trademarks include colors, sounds, scents, product shapes, motion graphics, and other distinctive elements that go beyond standard words or logos. These marks function the same way as traditional trademarks—they identify and distinguish the source of goods or services—but they do so through sensory or visual impressions that are unusual in the trademark landscape. Famous examples include the NBC three-tone chime, which is registered as a sound mark, and the Tiffany blue box, a registered color mark associated with luxury jewelry. While these marks can be powerful branding tools, they are notoriously difficult to register. Applicants must demonstrate that the non-traditional mark has acquired secondary meaning, meaning that consumers have come to associate the mark specifically with a single source or company. This usually requires extensive evidence, such as long-term use, widespread advertising, and consumer surveys. Without this proof, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office will not grant registration.

Registering your trademark with the USPTO is a critical step in securing long-term legal protection for your brand. Federal trademark registration not only provides nationwide rights but also puts competitors and the public on notice of your exclusive claim to the mark in connection with your specified goods or services. While common law rights may arise from actual use, only registration with the USPTO grants the full bundle of benefits, including access to federal courts and the ability to block imports of infringing goods.

Working with an experienced trademark attorney is highly recommended. Legal counsel can help you select a protectable mark, anticipate challenges (especially with descriptive marks or where secondary meaning may be required), and avoid rejections based on likelihood of confusion or procedural errors.

Understanding the types of trademarks available is the first step in securing your brand’s identity and building lasting trademark rights. Whether you use a fanciful name like “Coca-Cola®,” a certification mark, or a collective mark, choosing wisely now can save you from legal headaches, and enhance your business’s legal strength, in the future. For example, instead of calling a streaming service “Online Movies,” which is likely generic, opt for a creative name like “Flixtor” or “Zentube”, invented words with no direct descriptive meaning, offering more protection under the law.

If you need assistance with trademark selection and registration or other trademark matters, please contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

The patent application process is complicated, with many technical and procedural requirements that many businesses, entrepreneurs, and inventors are unaware of. The path from concept to patent grant takes considerable work, expertise, and time. Each stage of the process carries distinct legal and procedural requirements under U.S. patent law. This article details the steps involved in obtaining a utility patent through the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the typical timeline.

There are three main types of patents: utility patents, design patents, and plant patents. This article focuses on the utility patent application process. The patent application process in the United States is governed by federal statutes and regulations implemented by the USPTO. A patent grants the inventor exclusive rights to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the claimed invention for a limited term, typically 20 years from the original filing date of the utility patent application.

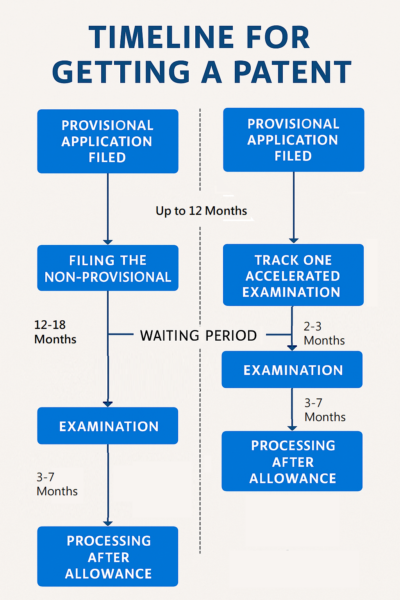

Typically, the patent application process takes anywhere from about one year from the time of the filing date to two or more years, depending on the complexity of the invention and the particular art unit that handles the application. Some art units are more impacted than others, leading to longer wait times. For example, art units that handle business methods, software-based inventions, and financial technologies (such as those within Technology Center 3600) often experience significantly longer average pendencies, ranging from three to five years or more before a final disposition. This is due to both high application volumes and more intensive scrutiny under 35 U.S.C. § 101, which deals with whether the application covers proper subject matter that is eligible for patent protection.

In contrast, applications assigned to less burdened art units, such as those handling mechanical inventions or certain chemical technologies (e.g., Technology Centers 1700 and 3700), often proceed more quickly, with some applications being examined and allowed within 12 to 18 months from the filing date.

Applicants can take specific actions to avoid unnecessary delays during the examination process, which are discussed below.

Before beginning the filing process, a thorough patent search is strongly recommended. This search helps determine whether the invention is novel and non obvious in light of prior art, which includes previously granted patents, published patent applications, and other publicly disclosed information.

A prior art search can identify references that may be cited during the examination process. The prior art search and analysis will indicate how smooth the examination process will be. If there is closely related prior art, then the examination process is going to be difficult and prolonged. Your patent attorney will likely need to submit multiple rounds of claim amendments and legal arguments to convince the patent examiner that your invention is patentable. The prior art search can also help the patent attorney craft the scope of the claimed invention to put the patent application in a better form for examination, allowing them to focus on the aspects of the invention that are distinct from the related search results.

There may be good reasons for filing a provisional patent application instead of a non provisional patent application. The decision affects the application process, patent rights, and timeline. A provisional patent application can be an attractive option for several practical reasons.

First, it can be a cost-effective way to secure an early filing date without the formalities and expense of a full utility non-provisional patent application, while still allowing the applicant to legally use the term "patent pending" in connection with the invention. This can be especially useful for startups, individual inventors, or early-stage companies that are seeking funding, evaluating market interest, or refining their invention before committing to the full costs of prosecution.

Second, a provisional application can serve as a strategic placeholder. It gives the applicant up to 12 months to further develop the invention, conduct market research, or seek partnerships while preserving the filing date as a priority date for any subsequent utility non-provisional application claiming benefit of the provisional.

Filing a provisional application does not initiate substantive examination by the USPTO and does not result in a patent grant unless a utility non-provisional patent application is filed within 12 months. This means that while the provisional filing preserves rights, it effectively delays the start of the examination process. As a result, the overall timeline to get a patent may be extended by up to one year. Nonetheless, this delay can be beneficial, as it provides time to improve the invention and prepare a stronger, more complete utility application.

In sum, the choice to file a provisional patent application can provide flexibility, cost savings, and strategic advantages, particularly when an invention is still being finalized or when immediate protection is needed while preparing for a full utility application.

A provisional application establishes a provisional filing date. It does not require claims, an oath or declaration, or formal drawings, but it must fully describe the invention to satisfy the written description requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 112. A provisional application gives the applicant 12 months to file a corresponding non-provisional application that claims the benefit of the provisional filing date.

The utility non-provisional patent application is the formal document examined by a patent examiner. It must include at least one claim, an abstract, a specification with sufficient detail, and drawings where applicable. This is the application that initiates the full examination process, leading either to a patent grant or final rejection.

Applications may be filed electronically through the USPTO’s Patent Center. To complete the filing process, applicants must submit several key documents, including a specification that describes the invention in detail, at least one claim that defines the scope of legal protection sought, and any necessary drawings that support the disclosure. An oath or declaration must also be included, affirming the inventorship and compliance with relevant legal standards. Additionally, applicants must pay several required fees, which include filing fees, a publication fee, and an issue fee.

Beyond these initial fees, applicants are also responsible for paying a search fee and examination fee as part of the review process. Once a patent is granted, ongoing responsibilities include the payment of maintenance fees at regular intervals to keep the patent in force. These fees are due at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after the date of patent grant and are critical to maintaining patent rights for the full term.

After submission, the utility patent application enters the examination process. A patent examiner at the patent office (USPTO) reviews the application for compliance with legal requirements such as novelty, non-obviousness, and adequate disclosure.

The examiner begins by performing a prior art search and comparing the claimed invention to existing references. This stage may take between 12 and 18 months after the filing of a nonprovisional application, depending on the assigned art unit and examiner workload. Following this search, most applications receive a first office action, which typically contains one or more grounds of rejection. This first office action is part of standard patent prosecution and does not terminate the application.

Applicants are given an extendable deadline of three months to respond to an office action in order to avoid incurring extension fees, though the deadline may be extended by up to three additional months with payment of appropriate fees. The typical back-and-forth with the examiner adds anywhere from 3 to 6 months to the overall timeline.

If the examiner maintains the rejections after a response, a second office action is often issued, and in many cases this will be a final rejection. Upon receiving a final rejection, applicants may file a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) to continue prosecution before the same examiner, which typically adds another 4 to 6 months to the pendency. Alternatively, applicants may choose to appeal the rejection to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), a process that may extend the application timeline by 1 to 2 years or more depending on the complexity of the issues on appeal.

Because of this iterative process, the total pendency of a utility application from filing to final disposition (either allowance or abandonment) can vary significantly, often ranging between 12 and 48 months. This timeframe depends not only on the responsiveness of the applicant but also on the nature of the invention and the efficiency of the assigned art unit.

Once the patent examiner reviews and allows the application, the applicant must pay the issue fee. After that, the patent grant is issued, conferring enforceable patent rights. Patent owners must continue to pay maintenance fees at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years to keep the patent active.

Applicants can take specific actions to avoid unnecessary delays during the examination process.

Submitting a complete and compliant application with well-drafted claims, a thorough specification, and high-quality drawings can help prevent early rejections. Promptly responding to office actions, avoiding unnecessary claim amendments that introduce new issues, and engaging in proactive interviews with the examiner can also facilitate more efficient prosecution.

Additionally, programs such as the Track One prioritized examination can reduce pendency to under 12 months for an additional fee and may be a worthwhile option for applicants seeking an expedited patent grant. Track One is available for utility and plant patent applications and allows for final disposition within about 12 months from the grant of prioritized status. To qualify, the applicant must submit a complete application with no more than four independent claims and thirty total claims, and pay an additional prioritized examination fee and processing fee.

Other acceleration programs also exist. Applicants who are 65 years or older, or whose health or other circumstances justify expedited handling, may file a petition to make special based on age or health. Also, first-time filers that also qualify as micro-entities can accelerate their applications with the submission of a form. These petitions are typically granted without requiring additional fees.

Participation in these programs can be especially valuable when the applicant is seeking early market entry, investment, or licensing opportunities. However, they require careful preparation to ensure eligibility and maximize the likelihood of success.

Patent attorneys play a critical role in crafting strong claims, responding to office actions, and ensuring procedural compliance. A patent attorney can also advise you as to the accelerated prosecution options that may be available to you. Consulting a qualified patent attorney is especially important for complex technologies or strategic filings.

A frequently asked question is, how long does it take to get a patent? The answer depends on several factors, including the technology area, filing completeness, examiner workload, and responsiveness to USPTO communications. As described in earlier sections, the type of application filed also plays a role. Filing a provisional patent application delays substantive examination by up to 12 months, as no action is taken by the USPTO unless a nonprovisional is filed within that time.

Following submission of a utility nonprovisional patent application, examination typically begins between 12 and 24 months later, depending on the assigned art unit. The initial office action generally issues within that time frame, and each round of examination and response can add 6 to 12 months. In the case of a final rejection, further actions such as an RCE (4-6 months) or appeal to the PTAB (1 to 2 years) can add significant time. As a result, the average timeframe for a final disposition, either a patent grant or abandonment, is a broad range of 12 to 48 months.

U.S. applicants may also pursue foreign patents through national or regional patent applications, such as those filed with the European Patent Office. Under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), a foreign application can be filed based on a U.S. utility application within 12 months to preserve priority.

During the national phase, applicants must comply with the legal and procedural requirements of each designated jurisdiction. Differences in examination, language, and formality rules can affect timing and outcomes.

Compared to the European Patent Office, where examination timelines also span several years, the U.S. pendency is an average timeframe compared to international patent offices. For applicants seeking a quicker path to issuance, several accelerated examination programs are available. The Track One prioritized examination program, for example, allows qualifying utility applications to reach a final disposition within 12 months from prioritized status for an additional fee. Other options, such as the Accelerated Examination Program or petitions to make special based on age or health, also provide pathways to expedited review. These programs can be especially beneficial for applicants pursuing time-sensitive commercialization or funding strategies.

The U.S. patent application process is complicated and requires a high degree of skill to handle successfully. Each phase requires careful attention and timely action.

There is no exact answer to the question "how long does it take to get a patent?". The answer depends heavily on how well the process is managed. We find that the average length of the process is in 18-24 month range, but it is highly variable. By engaging experienced professionals, inventors can maximize their chances of securing their intellectual property rights in a timely manner.

If you are considering pursuing a patent application, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

Businesses and entrepreneurs often face a critical problem: they fail to recognize patentable subject matter in their innovative products or services and inadvertently forfeit valuable patent rights by entering the marketplace without first filing a patent application. Whether developing cutting-edge digital technologies, advanced electronics, chemical innovations, novel consumer products, or new machinery, innovators must understand how to protect their creations from the outset.

In the United States, there is a limited grace period (12 months for utility patents and 6 months for design patents) after public disclosure, sale, or offer for sale of an invention during which a patent application can still be filed. If the application filed is not submitted within this grace period, the invention becomes part of the public domain, and the patent applicant permanently forfeits the right to obtain a patent grant for that invention.

First-time patent applicants, tech startups, and other innovators must understand when to initiate the patent process to avoid losing protection. Understanding patentable subject matter and recognizing potentially patentable innovations enables inventors to investigate patent protection and maximize the commercial value of their developments.

This article provides an overview of the types of inventions that may be protected under U.S. patent law pursuant to 35 U.S.C. §101. We also discuss important aspects of design patents, plant patents, and developments under European patent law to give innovators a comprehensive guide to safeguarding their innovations.

Under 35 U.S.C. §101, a patentable invention must be a "new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof." This definition encompasses substantially every invention that falls within the "useful arts," but it is not without limits.

The most common type of patent is a utility patent, which protects functional inventions and innovations. Four categories define utility patent eligibility under U.S. patent law, each requiring that the claimed invention be new, useful, and directed to eligible subject matter.

To be eligible, the invention claimed must meet the utility requirement, meaning it must serve an intended purpose and provide some identifiable benefit. While the threshold for utility is low, courts and the patent office have occasionally rejected inventions for lacking practical utility, such as perpetual motion machines or other devices that violate the laws of physics.

Despite the breadth of §101, courts have carved out certain judicial exceptions to what is considered patentable subject matter. Subject matter that falls into these judicially created categories are non-patentable:

A claimed invention that falls into one of these judicial exception categories is not patentable unless it includes additional elements that amount to "significantly more" than the judicial exception itself—a standard articulated in landmark cases such as Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank, 573 U.S. 208 (2014) (regarding abstract ideas implemented on a generic computer) and Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Labs, 566 U.S. 66 (2012) (regarding laws of nature in medical treatment methods). In practice, this means the invention must incorporate an inventive concept sufficient to transform the judicial exception into a patent-eligible application.

To be eligible for a patent grant, an invention must satisfy three primary patentability requirements: (1) it must be within the statutory subject matter defined by §101, (2) it must be novel under §102, and (3) it must be non obvious under §103. This article focuses on the first prong—patentable subject matter.

The novelty requirement ensures that a claimed invention is new and has not been disclosed in the prior art before the filing date of the patent application. Under 35 U.S.C. §102, an invention is anticipated, and therefore not novel, if a single prior art reference discloses each and every element of the claimed invention, either expressly or inherently. Anticipation requires that the prior art enable a person of ordinary skill to make and use the invention without undue experimentation. If an invention is anticipated, it cannot receive a patent grant because it does not add anything new to the public domain. Click for a more in-depth explanation of novelty.

The non-obviousness requirement, set forth in 35 U.S.C. §103, mandates that a claimed invention must not be an obvious variation of the prior art to a person having ordinary skill in the relevant field. Even if an invention is novel, it is not patentable if the differences between the invention and prior art would have been obvious at the time the patent application was filed. Courts assess non-obviousness by considering factors such as the scope and content of the prior art, the differences between the prior art and the claimed invention, and the level of skill in the pertinent art. Click for a more in-depth explanation of obviousness.

A critical step in determining whether your invention is patentable is conducting a thorough patent search and prior art search. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) evaluates whether the claimed invention is novel and non obvious in view of the prior art, which includes any printed publication, earlier patent applications filed, or known uses. As each patent application must be tailored to the unique attributes of an invention, a thorough prior art search is essential to achieving a patent grant.

In the U.S., an application filed can take the form of a provisional application or a non provisional application. A provisional application is a placeholder that establishes an early filing date but is not examined. A non provisional application is the full patent application examined by the USPTO.

A design patent protects the ornamental appearance of an article of manufacture, rather than its utilitarian features. Unlike a utility patent, which protects how an invention works, a design patent protects how an article looks. This includes the shape, surface ornamentation, or a combination of both applied to an article of manufacture.

To qualify for design patent protection, the design must meet several specific requirements:

The scope of protection for a design patent is limited to the visual features shown in the submitted drawings, making the preparation of accurate and comprehensive drawings critical to the patent process. Term protection for U.S. design patents is 15 years from the date of patent grant, with no maintenance fees required during that period. Click for a more in-depth explanation of design patents.

Under 35 U.S.C. §161, a plant patent may be granted to anyone who invents or discovers and asexually reproduces any distinct and new variety of plant. The plant must be asexually reproduced (not grown from seed), not found in an uncultivated state, and distinct from known varieties. Examples include new rose or apple tree cultivars. Like utility patents, plant patents last for 20 years from the filing date. Click for a more in-depth explanation of plant patents.

Under European patent law, the criteria are slightly different but similar in concept. The European Patent Convention (EPC) recognizes patentable inventions if they have industrial applicability, are novel, and involve an inventive step. Under EPC Article 56, the "inventive step" requirement is akin to obviousness; what matters is whether the claimed invention would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art, considering the state of the art as a whole.

Software inventions, for example, are treated more restrictively in Europe and must provide a "further technical effect" beyond a basic computer implementation. European practice also places emphasis on technical processes and disallows claims that are purely business, aesthetic, or mental in nature.

A valid patent gives the patent owner the exclusive right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the patented invention for a limited time. For utility patents in the U.S., that term is generally 20 years from the earliest effective filing date, subject to the payment of maintenance fees.

Ownership initially resides with the named inventors unless assigned. Patents can enter the public domain if maintenance fees are not paid, or if the patent expires.

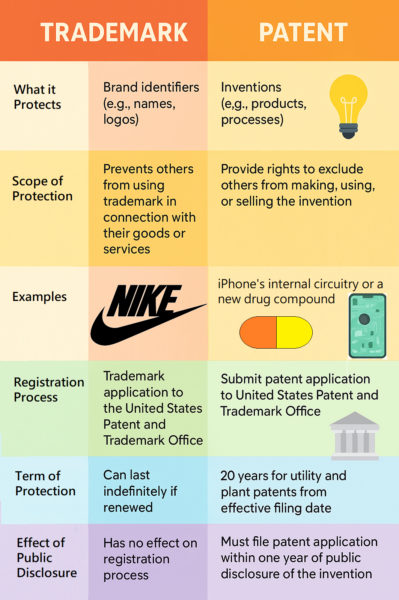

It is important to distinguish patents from other forms of intellectual property, as different types of legal protection cover different aspects of creative and commercial endeavors.

Understanding these distinctions is essential for securing comprehensive intellectual property rights. Innovators often seek overlapping protection—for example, by obtaining patent protection for functional features, copyright protection for related written materials or designs, and trademark protection for product names and logos—to create robust legal safeguards for their creations and business assets.

Entrepreneurs that innovate and development novel products and services should understand how to identify patentable innovations. Whether your innovation is a composition of matter, a technical process, a novel design, or a new plant variety, being able to recognize whether it includes patentable subject matter can mean the difference between acquiring intellectual property rights or forfeiting them.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

The written description requirement under 35 U.S.C. §112(a) plays a foundational role in U.S. patent law. This requirement mandates that a patent specification contain a "written description of the invention" in a full and clear manner. Over decades, this statutory provision has evolved through jurisprudence to function as a gatekeeping doctrine that ensures an inventor was in "possession of the claimed invention" as of the filing date. This article surveys the written description requirement, including its statutory foundation, major case law, how it is applied by the courts and United States Patent and Trademark Office, and practical tips for satisfying the requirement.

The written description requirement is codified in the first paragraph of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a), which provides that the application must contain a written description of the invention, including the process of making and using it, in a full, clear, and concise manner as to enable any person skilled in the art to determine that the applicant was in possession of the claimed invention as of the filing date.

This language has been consistently interpreted by the courts to impose two distinct but related requirements: (1) a written description of the invention, and (2) enablement. The first clause—“a written description of the invention”—is not merely a preamble to the enablement requirement, but an independent obligation. The Federal Circuit reaffirmed this principle in Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2010), where the court held: “Section 112, para. 1, contains a written description requirement separate from the enablement requirement.”

In Ariad, the court emphasized that the statutory phrase “written description of the invention” refers to a disclosure that clearly allows a person of ordinary skill in the art to conclude that the inventor was in possession of the claimed invention as of the filing date. This requirement ensures that the claims define what the applicant actually invented, and are not speculative or based on an after-the-fact realization.

The statute is thus interpreted to require that the specification “conveys with reasonable clarity to those skilled in the art that, as of the filing date, the inventor was in possession of the invention,” as later claimed. The inquiry is factual in nature, assessed on a case-by-case basis, and varies depending on the complexity and predictability of the field of invention.

The written description requirement and the enablement requirement are distinct yet related obligations under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a). While both serve to ensure that the inventor has sufficiently disclosed their invention, they address different questions.

The written description requirement asks: Did the inventor actually invent the claimed subject matter as of the filing date? It focuses on demonstrating that the inventor had possession of the claimed invention and conveyed it with sufficient detail in the specification. In contrast, the enablement requirement asks: Can a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA) make and use the claimed invention without undue experimentation based on the disclosure?

For example, in Ariad v. Eli Lilly, the claims were directed to methods of reducing NF-κB activity. Although the specification described the desired biological effect and hypothesized mechanisms, it failed to describe any actual molecules or working examples that achieved the disclosed function. The court found a lack of written description because the inventors had not yet conceived how to perform the invention.

In contrast, a claim might satisfy the written description requirement but fail enablement if the invention is clearly possessed but the disclosure does not teach a POSITA how to practice the invention without "undue experimentation" (extensive research). For instance, where the applicant describes a complex genetic construct with no guidance on how to synthesize or deliver they may show possession but not enablement.

Thus, written description ensures the inventor had the idea, while enablement ensures the public can practice it. Both are required for valid claims.

At the core of the written description requirement is a fundamental and fact-intensive inquiry: Did the inventor possess the claimed subject matter as of the filing date? This inquiry is rooted in the statutory mandate of 35 U.S.C. §112(a), which requires that the specification contain a “written description of the invention.” The Federal Circuit has repeatedly emphasized that the purpose of this requirement is to ensure that the inventor had fully conceptualized and was in possession of the claimed invention when the application was filed—not merely an unformed idea or a research plan with a hoped-for result.

This possession standard is not satisfied merely by describing an end goal or a broad concept. Rather, the specification must convey with reasonable clarity to a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA) that the inventor had actually invented what is being claimed. This is evaluated from the perspective of the POSITA, taking into account the nature and predictability of the technology, and the level of detail required to reflect possession will vary accordingly.

The question of whether there is adequate written description is a fundamental factual inquiry that takes into consideration the entirety of the application, including the specification, drawings, and claims to determine whether there is sufficient evidence that the invention was captured in the original filing on the filing date sought. Possession may be demonstrated in a variety of ways, depending on the context and subject matter. The Federal Circuit has identified several illustrative examples of how written description may be satisfied:

In chemical and biotech cases, where claims are directed to compounds or molecules, the inclusion of precise structural chemical formulas may provide conclusive evidence of possession. For instance, in Amgen Inc. v. Chugai Pharm. Co., 927 F.2d 1200 (Fed. Cir. 1991), the Federal Circuit stated that a claim to a specific DNA sequence lacked written description where the specification failed to disclose the sequence itself or any means to predict it.

The Federal Circuit considered whether certain claims in Amgen’s ‘008 patent, covering DNA sequences encoding erythropoietin (EPO), were valid under the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112. The dispute centered on whether the description in the application relied on by Amgen to demonstrate possession of the full scope of DNA claims, particularly those generically claiming any sequence encoding a polypeptide “sufficiently duplicative” of EPO to exhibit its biological activity, sufficiently supported the claims.

The Federal Circuit invalidated claims 7, 8, 23–27, and 29 for lack of written description. These claims drawn to generic DNA sequences were not sufficiently supported by the disclosure, which described only a limited number of EPO analogs. Although the specification asserted that numerous analogs could be created, the court found that Amgen had provided insufficient examples and technical guidance for producing DNA sequences other than the few disclosed. The court emphasized that the claims require a broad genus of DNA sequences, yet the specification only described and enabled a small subset.