Trademark fair use is the use of another's trademark or service mark in manner that does not constitute trademark use. Trademark fair use is a defense to a claim of trademark infringement. Fair use does not qualify as infringement and is lawful. There are two main types: classic fair use and nominative fair use. This article explains trademark fair use and provides examples.

Trademark fair use is a legal principle that allows individuals or businesses to use another’s trademark without infringing the trademark owner’s rights, where the trademark is not used in the nature of a source identifier. There are two primary categories of trademark fair use. These are classic fair use and nominative fair use. Classic fair use occurs when a trademark is used descriptively, without implying that the trademark owner endorses or is affiliated with the user. Nominative fair use, on the other hand, permits the use of a trademark to identify the goods or services of the trademark owner when there is no other practical way to do so.

The Lanham Act forms the legal foundation for the fair use of trademarks, setting guidelines to prevent confusion about the source of goods or services while allowing certain uses of trademarks. Factors influencing fair use determinations include good faith, necessity of description, and potential consumer confusion. Trademark fair use is essential for fostering competition and innovation. It allows businesses to accurately describe their products, compare them to others, and provide consumers with valuable information. Without this doctrine, the marketplace would be stifled, and consumers would be deprived of critical information needed to make informed decisions.

Businesses should have a good understanding trademark fair use, as misunderstanding this concept can lead to legal missteps and litigation. The trademark fair use doctrine is not just a legal shield but a facilitator of free expression and informative commercial communications. The doctrine allows businesses engage in comparative advertising, and contribute to news stories without overstepping legal protections.

Trademark fair use is a legal doctrine that allows certain uses of trademarks without permission to prevent confusion about the source of goods or services. Classic fair use applies when a trademark is used descriptively, meaning it describes the user’s own products rather than indicating their source. This type of use is also known as descriptive fair use and is crucial for businesses to describe their goods or services accurately.

Nominative fair use permits the use of a trademark. This occurs when it is essential to identify the goods or services of the trademark owner. This type of fair use is particularly important when there is no other practical way to refer to a product or service without using the trademark. For example, using the term “iPhone” to describe a compatible accessory is often deemed nominative fair use.

Factors influencing fair use determinations include the necessity to describe goods, the potential for consumer confusion, and the good faith of the user. Understanding these factors helps businesses and individuals make informed decisions about the use of trademarks and navigate potential legal challenges.

Trademark fair use encompasses two primary categories: descriptive fair use and nominative fair use. Each type serves a unique purpose and has specific conditions under which it applies.

Understanding these types is essential for navigating the legal landscape and ensuring compliance with trademark law.

Descriptive fair use allows the use of a trademark to describe a user’s own products rather than indicating the source. This type of fair use is particularly relevant for descriptive trademarks, which include terms that describe a characteristic of the goods or services. For instance, the term “American Airlines” is descriptive of an airline service. Descriptive fair use permits the application of these terms to describe an airline providing service in America: Delta airlines is an American airline. The defense of descriptive fair use allows businesses to describe their products accurately without implying endorsement, thus providing a descriptive meaning to the terms used.

In King-Seeley Thermos Co. v. Aladdin Industries, Inc. (2d Cir. 1963), the term "thermos" to describe vacuum-insulated bottles. The court found that while "thermos" was originally a trademark, it had become genericized due to widespread public use. However, the court also recognized that consumers still associated the term with the original manufacturer, King-Seeley. To balance these interests, the court allowed competitors to use "thermos" descriptively, but only in lowercase and with modifiers to distinguish their products from the original Thermos brand. This case established the principle that trademarks can lose their exclusive status if they become generic, but that some limited descriptive use may still be permissible.

However, descriptive fair use comes with limitations. If the use of a descriptive term causes confusion among the public, fair use would no longer apply. Therefore, it is crucial for businesses to ensure that their use of descriptive trademarks does not mislead consumers about the source of the products. This balance is essential to maintain the integrity of the trademark while allowing descriptive use.

Moreover, descriptive fair use generally involves descriptive, geographically descriptive, and personal names. Fanciful and arbitrarily suggestive trademarks, which are inherently distinctive, do not fall under descriptive fair use and are protected against such uses.

Nominative fair use allows the use of another’s trademark. This is permissible when referring to the trademark owner’s goods and services under certain conditions. This type of fair use is particularly relevant when there is no other practical way to identify the product or service without using the trademark. For example, using the term “Lexus” to refer to a Lexus car in a review or advertisement is considered nominative fair use.

Nominative fair use qualifies if the use of the trademark meets certain criteria. Firstly, the product or service must not be readily identifiable without the use of the trademark. Secondly, only as much of the trademark as necessary should be used to identify the goods or services. Lastly, the use should not imply sponsorship or endorsement by the trademark holder or the trademark owner.

In New Kids on the Block v. News America Publishing, Inc. (9th Cir. 1992), News America Publishing conducting polling about the musical group News Kids on the Block (NKOTB). NKOTB sued for trademark infringement for the use of their name in the poll. The court found "nominative fair use", which allows the use of a trademark to identify a person, place, or thing in a factual manner without the use for trademark purposes. The court held that using the band's name in a poll about the band was permissible because there was no other way to refer to the band without using its trademarked name . This case is significant because it recognizes that some uses of trademarks are necessary for communication and should not be considered infringement.

Nominative fair use enables businesses and individuals to engage in comparative advertising, product reviews, reporting and journalism, and other forms of commentary without infringing on trademark rights. It helps maintain a balance between protecting trademark owners and allowing necessary uses of trademarks for identification and communication, including the nominative fair use defense.

Trademark fair use is relevant in various practical contexts, such as comparative advertising, product reviews, and parodies. These applications demonstrate how the principles of fair use support free speech, competition, and important consumer information.

Comparative advertising is a common example of trademark fair use. It allows businesses to use another’s trademark to compare products and highlight differences, benefiting consumers and the marketplace. Under trademark law, using another’s trademark for comparison in advertisements is permitted, provided it is done in good faith and does not mislead consumers.

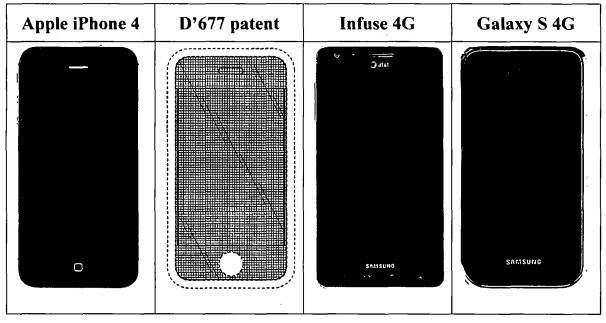

Nominative fair use often occurs in comparative advertising when consumers recognize another’s trademark or else’s trademark upon identification. For instance, an advertisement comparing the features of two smartphones might use the trademarks of both brands to make the comparison clear and effective. However, it is essential to use only as much of the trademark as necessary to avoid implying endorsement or sponsorship.

While comparative advertising can be beneficial, it also carries risks. Claims of superiority must be substantiated to avoid legal problems, and any misleading comparisons can lead to disputes and potential trademark infringement claims. Therefore, businesses must exercise caution and ensure their comparative advertising is accurate and fair.

Product reviews and commentary are protected under nominative fair use, allowing the public to discuss, compare, and critique protected trademarks. Mentioning a brand name is often necessary to provide a meaningful review or comparison of goods or services. This type of fair use is crucial for consumers and media, as it enables informed decision-making and fosters transparency.

Parody and criticism fall under the umbrella of trademark fair use, provided they clearly indicate that the content is a joke and not an affiliated promotion. Parody uses humor or satire to comment on a trademark, and it must be evident to the audience that it is not an endorsement by the trademark owner.

For instance, a parody of a popular brand’s advertisement that humorously exaggerates its claims can be permissible under fair use, as long as it avoids misleading consumers about sponsorship. In the Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC case, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed the boundaries of parody as a defense under trademark law. VIP Products marketed a dog toy resembling Jack Daniel's whiskey bottle, substituting "Jack Daniel's" with "Bad Spaniels" and altering other label elements humorously. Jack Daniel's contended this infringed and diluted its trademarks. VIP Products countered, asserting First Amendment protection due to the parodic nature of the toy.

The Court unanimously ruled that when a trademark is employed to identify the source of the defendant's own goods—essentially using the trademark as a trademark—the First Amendment does not automatically shield such use from infringement claims. Consequently, the standard likelihood-of-confusion analysis under the Lanham Act applies, even for parodic expressions.

This decision delineates the limits of parody as a fair use defense in trademark law. While parody can serve as commentary or criticism, its protective scope is not absolute. The Court emphasized that the mere presence of humor or parody does not exempt a defendant from liability if the use confuses consumers regarding the source or sponsorship of goods. Therefore, entities employing another's trademark in a parodic context must ensure their use does not mislead consumers about the origin of the products to avoid infringement liability.

The concept of fair use is acknowledged globally, but its application varies by jurisdiction. While some regions may not label it as fair use, similar principles apply to allow certain uses of trademarks. Businesses and individuals must familiarize themselves with local trademark laws to navigate trademark usage effectively. Common law jurisdictions, such as the United States, employ fair use principles in trademark cases, allowing certain usages of marks. However, the subjective nature of fair use means that interpretations can vary across different legal contexts, making it essential to understand the specific requirements of each jurisdiction.

Companies operating internationally must be particularly careful, as what is considered fair use in one country might not be legally allowed in another. Staying informed about local laws and regulations is crucial to avoid legal disputes and ensure compliance.

For businesses, understanding trademark fair use is vital to safeguard their brands and avoid unintentional infringements. Companies should educate stakeholders about trademark rights and monitor how trademarks are used, especially in digital spaces like social media and e-commerce. This proactive approach can significantly reduce the risk of infringement.

Additionally, businesses should stay informed about changes in trademark laws as they can impact operations and compliance. Avoiding the use of widely recognized descriptive trademarks that may lead to confusion is also essential. By navigating trademark fair use carefully, businesses can protect their intellectual property and operate within legal boundaries.

Asserting fair use comes with potential risks and challenges. Trademark owners may challenge the legitimacy of the fair use claim, leading to litigation risks. Engaging in comparative advertising using fair use can result in legal disputes if the comparison is seen as misleading or unfair. Therefore, businesses must carefully apply fair use principles accurately to avoid trademark infringement claims, which can have significant financial consequences.

Consulting an trademark attorney is essential to assess cases and ensure proper application of fair use. If you’re unsure whether your use of a trademark qualifies as fair use, an attorney can provide clarity and guidance. They can also assist in responding to cease-and-desist letters and handling any legal disputes.

Legal counsel is crucial for businesses and individuals facing challenges or disputes regarding trademark usage. An attorney can help you understand your rights and obligations, ensuring that your actions are legally sound and protect your interests.

Trademark fair use is a complex yet essential concept for businesses and individuals. Understanding its types, applications, and legal framework can help navigate potential legal challenges and support fair competition. By applying fair use principles correctly, businesses can describe their products accurately, engage in comparative advertising, and contribute to informative discourse without infringing on trademark rights.

Staying informed and consulting with legal experts can ensure that your use of trademarks remains within legal boundaries.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

Prior art is evidence that an invention was publicly known before the filing date of a patent application. It can be in many forms, such as existing patents, written publications, videos, and other forms of public disclosure. Prior art matters because if it is sufficiently similar to an invention, it can render the invention unpatentable. Grasping the concept of what is prior art is and how it affects patentability is essential for understanding what can be patented. This article will explore various types of prior art and the role of prior art in the patent examination process.

To truly grasp the significance of prior art, we must first define it under U.S. law. According to federal statute 35 U.S.C. § 102, as amended by the America Invents Act, prior art encompasses any evidence that an invention was known or available to the public before the effective filing date of a patent application. Any public disclosure of the invention before the filing date can challenge its originality, novelty, and patentability.

The timing of public disclosure is crucial. For a public disclosure to qualify as prior art, it must have been disclosed or available to the public before the filing date of a patent application. Information disclosed after this date does not qualify as prior art. This emphasizes the importance of filing a patent application promptly to avoid potential conflicts with third party disclosures. In other words, you want to beat competitors and other parties to the punch. However, in the case of a previously filed patent application, it may qualify as prior art even if it is not publicly available. The prior filed application can still qualify as prior art if it was filed before the new application.

Prior art is the basis upon which the United States Patent and Trademark Office determines patentability. There are two analyses that the patent office conducts in view of the prior art: whether the claimed invention is novel and whether the claimed invention is non-obvious. The novelty and non-obvious requirements are discussed below.

Under U.S. patent law, the novelty requirement ensures that an invention is new and has not been disclosed in prior art before the patent application’s filing date. This requirement is codified in 35 U.S.C. § 102, which outlines the conditions under which an invention is considered novel.

An invention lacks novelty if it is anticipated by a single prior art reference, meaning every element of the claimed invention is disclosed, either explicitly or inherently, in that reference. The all-elements rule for anticipation under U.S. patent law requires that a single prior art reference disclose each and every element of a claimed invention to invalidate the claim for lack of novelty. If even one claimed element is missing from the reference, the claim is not anticipated. The rule is grounded in the principle that anticipation requires the invention to have been fully disclosed in a single reference so that it is not truly "new". This rule generally applies in other national patent offices as well.

Section 102 changed between pre-AIA (America Invents Act) and post-AIA frameworks. Under the pre-AIA framework, novelty is determined based on whether the invention was known, used, or described in a printed publication or patented in the U.S. or abroad before the date of invention. However, the AIA, effective March 16, 2013, shifted US patent law to a "first inventor to file" system, where the relevant date is the filing date rather than the invention date. The US is thus a first-to-file system and prior art is evaluated based on whether it pre-dates the earliest filing date of the patent application.

The non-obviousness requirement under U.S. patent law ensures that an invention is not only new but also represents a meaningful technical advance that would not have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time the patent application was filed. This requirement is codified in 35 U.S.C. § 103, which states that a patent cannot be obtained if the differences between the claimed invention and prior art would have been obvious to someone skilled in the relevant field.

The landmark case Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1 (1966), established the framework for evaluating non-obviousness, known as the Graham factors. These include: (1) determining the scope and content of the prior art, (2) assessing the differences between the prior art and the claimed invention, (3) understanding the level of ordinary skill in the art, and (4) considering secondary factors such as commercial success, long-felt but unresolved needs, and failure of others.

In KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007), the Supreme Court emphasized a flexible approach to obviousness, in which the Court emphasized that a combination of prior art references or the knowledge of one of ordinary skill in the may render an invention obvious if there is some articulated reason or motivation to make such a combination that existed prior to the filing date of the application.

Non-obviousness serves to prevent patents on trivial or routine improvements, ensuring that the patent system rewards only innovations that include a genuine inventive step while maintaining a competitive market for incremental advancements easily within the grasp of skilled practitioners.

Prior art encompasses various forms of information relevant to the patentability of an invention. It is not limited to existing patents and products. Beyond existing patents, prior art can include public disclosures, scientific papers, technical journals, and any other forms of literature that provide relevant information before the filing date of a patent application. Identifying prior art from this wide array of sources can be complex and painstaking. To find the relevant prior art, a diversity of sources must be searched.

Printed publications are prior art under 35 USC 102(a)(1). Specifically, a person is not entitled to a patent if the claimed invention was described in a printed publication of any kind (e.g., a patent, journal article, blog post, product description on a website, etc.), or in public use (e.g., a device used in an open or public manner by the inventor), on sale (e.g., a product that is available to the public), or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention. Printed publications must be publicly accessible, such as being indexed in a library or available online, to qualify as prior art under § 102(a)(1).

Previously filed patents and published applications qualify as printed publications under 35 USC 102(a)(1). They are reliable references for the state of the art at the time of filing and are typically the primary source of prior art for the patent office in the patent examination purposes.

Under 35 USC 102(a)(2), issued patents and published applications are considered prior art if they existed before the effective filing date of a new invention. Thus, there are situations where material that was unpublished at the time your patent application is filed that can serve as prior art to your invention. Thus, prior art searches cannot be certain to uncover all relevant prior art. However, it is still of great importance to conduct a thorough prior art search prior to filing a new application.

Non-patent literature, such as scientific papers, articles, and technical journals, are also prior art if they are sufficiently thorough and complete in describing the invention. If publicly accessible and providing relevant information before the filing date, these documents can serve as prior art. This type of literature must be searched for and considered in assessing the patentability of an invention.

Various forms of non-patent literature, including research articles and technical papers, can significantly impact the patentability of an invention. By providing a wealth of information on existing technologies and innovations, these documents can help patent examiners determine whether a new invention is truly patentable.

Public disclosures, such as presentations at trade shows, conferences, and other public events, can be deemed prior art if they disclose an invention to the public before the filing date of a patent application. Any public presentation, lecture, or event revealing the invention can impact its patentability.

These public disclosures can significantly affect the assessment of originality of an invention claimed in a patent application. By making information publicly accessible, such disclosures provide a basis for patent examiners to compare the claimed invention against existing knowledge and determine its novelty and non-obviousness.

A sale of an invention prior to filing a patent application can create prior art, barring patentability under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(1). An invention offered for sale by a third party prior to the filing of the application or by the applicant more than one year before the application filing date is considered prior art.

Although many types of information can be considered prior art, some categories do not qualify. Non-enabling publications, for instance, cannot be classified as prior art if they do not provide sufficient description of the invention to enable someone of ordinary skill in the relevant field to replicate the invention. In other words, vague or incomplete disclosures are not considered prior art.

Unpublished patent applications, trade secrets, and publications that are not accessible to the public at the time of filing are not considered prior art because they remain undisclosed and unavailable for public scrutiny. Understanding what is not considered prior art is just as important as knowing what is.

There are also exceptions to what would otherwise be considered prior art. For instance, under 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) certain disclosures are not deemed prior art if the subject matter disclosed was obtained directly or indirectly from the inventor or if subject matter disclosed by a third party had previously been publicly disclosed by the inventor before the effective filing date.

A thorough prior art search is crucial for identifying existing inventions that may affect the novelty of a new patent application. This process involves systematically searching through various sources of prior art to ensure that the invention is truly novel and non-obvious.

Structured approaches and effective strategies can significantly increase an inventor’s chances of securing granted patents. A patent search can also identify potential patent infringement issues that should be considered before pursuing a patent and providing a new product or service.

Patent databases like USPTO enable efficient searches of both issued patents and pending applications. The USPTO’s Patent Public Search tool offers a tool to access US Patent prior art. Other publicly available tools, such as Google Patents, Espacenet, and Free Patents Online can also be used to search for patent documents. Utilizing patent citation data can enhance searches by connecting related patents and identifying previously referenced prior art. Additionally, Global Dossier tools provide access to file histories of related applications across international patent offices, offering a more in-depth understanding of prior art and its implications.

Patent attorneys, with their expertise in navigating complex patent databases, can advise on search strategy. Their knowledge and experience ensure thorough and effective patent searches, providing a solid foundation for the patent application process. Comprehensive prior art searches require refined search techniques. Experienced patent attorneys thoroughly understand the patent search databases offered by the USPTO, EPO, and others and are adept at using them.

Patent attorneys can help ensure that the pertinent prior art is identified and accounted for in the patent application process. They can enhance the quality of the prior art search and provide expert analysis of the findings, ensuring thorough and effective searches. Attorney analysis of the search results can provide valuable insights into the patentability of an invention.

Patent examiners use prior art as a reference point to evaluate the claims of an invention against established knowledge and technology. The examination process compares the claimed invention in a patent application with relevant prior art to determine if the invention is novel or previously disclosed. This ensures that the invention meets the legal requirements for patentability, including novelty and non-obviousness.

The examiner's process includes finding prior art in the same field covering related technologies and comparing this prior art to the claimed invention to determine whether one of ordinary skill in the relevant art would find the invention novel and non-obvious. The patentability of the invention depends on the degree of difference from existing art. This process underscores the importance of a thorough prior art search to identify potential prior art problems and assess the patentability of the invention before the examiner conducts their search and analysis.

Mitigating risks associated with prior art is essential for successful patent applications. Conducting early searches, continuous monitoring, and effective disclosure management can significantly enhance the chances of securing a patent and protecting intellectual property.

Conducting prior art searches early helps identify potential obstacles to patentability before significant time and resources are invested in development. An effective prior art search requires a systematic approach, including identifying relevant databases and keywords.

Consulting with a patent attorney can provide valuable insights and expertise to ensure that prior art searches are thorough and effective. Their knowledge of patent law and search techniques can help uncover potential conflicts and guide inventors towards successful patent applications.

Continuous monitoring of new publications and patents can keep you competitive and informed. Patent databases and online alerts efficiently track relevant patents and publications, ensuring inventors stay aware of new developments that may affect their inventions.

Routine checks of academic journals, patent databases, and industry news can result in more informed decision-making and provide a competitive edge in the market.

Managing public disclosures properly is vital to maintain the potential for patentability in future applications. Strategic management of public disclosures protects the patentability of inventions by minimizing unintentional prior art creation by disclosure of your own technology. Once you disclose your own invention in a public manner, there is a 12-month grace period in the US for filing a patent application for the invention. If you fail to file within that 12-month grace period, your invention becomes public domain and can be practiced by anyone without a license or permission. In some other countries, the grace period is shorter or there may be no grace period at all. Also, premature sharing of ideas that evolve into an invention could compromise patentability of that invention. You need a confidentiality process and policy to avoid unintentional disclosures that may affect the patentability of your inventions down the road.

It is critical for innovators to understand prior art and how it factors into the patentability of an invention. If you are an inventor or you have a business that is actively innovating, you need to be aware of the role of prior art. If you need assistance with assessing the patentability of an innovation or any other patent matter, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

The "public domain" is a fundamental concept in copyright law, referring to the body of works that are not protected by copyright and, as a result, are freely available for anyone to use without permission or the need to pay royalties. Works in the public domain can be reproduced, adapted, and distributed without restriction, thereby fostering creativity and innovation. However, before you start using old, famous literary, audiovisual, and visual works of art, you should understand the applicable copyright law, which will vary depending on when a work is created and published.

Federal copyright law protects a work from the moment it is created and fixed in a tangible form, such as paper, recording, or digital photograph. The length of copyright protection depends on factors like the author’s life and the type of work. For most works, copyright lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years. Once the copyright term expires, the work enters the public domain, allowing anyone to use it without permission from the author. Copyright protection can be formally secured through registration with the copyright office, which provides additional legal benefits. It’s important to note that copyright laws vary by country, so understanding copyright protection is essential for both creators and users to navigate their rights and responsibilities effectively. Proper awareness ensures compliance with copyright laws and supports the lawful sharing and use of creative works.

Categories of material that are not eligible for federal copyright protection include ideas and facts, works with expired copyrights, and works with no original authorship. U.S. government works are generally not eligible for federal copyright protection unless written by non-government authors under federal funding or produced by state governments. Scientific principles, theorems, mathematical formulae, laws of nature, and research methodologies are also excluded from copyright protection. Copyright law does not protect titles of books or movies, short phrases, facts, ideas, or theories. Similarly, words, names, numbers, symbols, signs, rules of grammar and diction, and punctuation cannot be copyrighted. Public domain works, such as public domain images, sound recordings, and other creative materials, become immediately accessible for unrestricted use. These exclusions ensure that fundamental tools for creativity and knowledge remain accessible, fostering innovation and public benefit. Let me know if further refinements are needed.

A copyrighted work may enter the public domain in the following ways:

Unpublished works created, but not published before January 1, 1978, are subject to special transitional rules:

When a work is dedicated to the public domain, it is free for anyone to use, but this process is rare and requires express authorization. Dedication occurs when a copyright owner relinquishes all rights to the work, allowing unrestricted use by the public.

Only the copyright owner—not necessarily the creator—can dedicate a work to the public domain. This distinction matters because creators who have transferred their copyright to another party, such as a publisher, may lack the authority to make such a dedication.

To dedicate a work, the copyright owner must take clear and intentional steps, such as issuing a formal statement, providing an explicit notice on the work indicating it is public domain, or using tools like Creative Commons Zero (CC0). These tools enable the owner to waive all copyright claims, affirming the public domain status of the work.

If you encounter a work claimed to be in the public domain by dedication, it is crucial to verify the dedication with the copyright owner. Documentation or explicit confirmation ensures that the dedication is valid and legally enforceable. Once a work is confirmed as dedicated to the public domain, it can be freely used without permission. However, proper diligence in verifying the dedication protects against inadvertent infringement.

Determining whether a work is in the public domain requires examining its publication date and adherence to statutory formalities. The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 significantly impacted the length of copyright terms for works under the Copyright Act of 1909.

The Sonny Bono Act extended copyright terms by 20 years, meaning many works that would have entered the public domain earlier are still under copyright. For example, works published in 1929 were protected until the end of 2024. Understanding these complexities ensures proper use of public domain materials.

Each year, works whose copyrights have expired enter the public domain. This process allows the public to freely access and use classic literature, music, films, and more. Below are some notable examples for 2024 and 2025:

Several notable works from 1928 lost their copyright protection in the United States on January 1, 2024.

Literature

| Title | Author/Creator | Type of Work | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| The House at Pooh Corner | A. A. Milne | Children's Book | This heartwarming story continues the adventures of Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends in the Hundred Acre Wood, with the introduction of the bouncy Tigger. The narrative, filled with gentle humor and charming illustrations by E.H. Shepard, explores themes of friendship, kindness, and the simple joys of childhood. |

| Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up | J. M. Barrie | Play | This timeless tale of Peter Pan, a boy who refuses to grow up, and his adventures in Neverland with the Darling children has captivated audiences for over a century. The play, first performed in 1904, explores themes of childhood, imagination, and the conflict between innocence and adulthood. It has been adapted numerous times for stage and screen, including a 1911 novel titled Peter and Wendy. |

| The Threepenny Opera | Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill | Play | A groundbreaking musical play that offers a satirical critique of capitalism and societal norms, The Threepenny Opera features memorable songs like "Mack the Knife" and has had a lasting impact on musical theater. |

| The Well of Loneliness | Radclyffe Hall | Novel | A groundbreaking and controversial work for its time, The Well of Loneliness explores lesbian themes and relationships with unprecedented frankness. Published in 1928, the novel faced censorship and legal challenges due to its depiction of same-sex love. |

| Decline and Fall | Evelyn Waugh | Novel | This satirical novel, marking Waugh's debut, offers a witty and often biting critique of English society in the 1920s. The story follows the misadventures of Paul Pennyfeather, an innocent student expelled from Oxford and thrust into a world of eccentric characters and absurd situations. |

| Millions of Cats | Wanda Gág | Children's Picture Book | One of the oldest American picture books still in print, Millions of Cats tells the enchanting story of a very old man who sets out to find a cat and ends up with millions of them. With its simple text and charming illustrations, the book has delighted generations of children. |

| West-Running Brook | Robert Frost | Poetry Collection | This collection showcases Robert Frost's mastery of language and his profound reflections on nature, humanity, and the passage of time. The poems explore themes of rural life, the beauty of the natural world, and the complexities of human relationships. |

| The Front Page | Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur | Play | A fast-paced and cynical portrayal of the world of reporters and editors in 1920s Chicago, The Front Page is a classic of American journalism. The play, known for its witty dialogue and colorful characters, captures the energy and corruption of the newspaper industry. |

| Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Adventure Novel | This thrilling adventure novel introduced the iconic character of Tarzan, a man raised by apes in the African jungle. Tarzan's story, filled with action and exotic locales, has spawned numerous sequels, film adaptations, and other media. |

| Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization | Margaret Mead | Anthropological Study | This influential anthropological study challenged traditional Western views of adolescence and sexuality. Mead's research in Samoa suggested that adolescence was not inherently a period of turmoil and that cultural factors played a significant role in shaping adolescent experiences. |

| The Missing Chums, Hunting for Hidden Gold, and The Shore Road Mystery | Franklin W. Dixon | Children's Novels (The Hardy Boys series) | These early installments in the popular Hardy Boys series introduced the young detective brothers Frank and Joe Hardy. The books, filled with mystery and adventure, have entertained generations of young readers. |

| The Trumpeter of Krakow | Eric P. Kelly | Children's Historical Novel | Set in medieval Poland, The Trumpeter of Krakow tells the story of a young trumpeter who plays a crucial role in defending the city of Krakow. The novel combines historical detail with adventure and suspense. |

| Lady Chatterley's Lover | D.H. Lawrence | Novel | A controversial novel exploring the physical and emotional relationship between a working-class man and an upper-class woman, Lady Chatterley's Lover was banned for many years due to its explicit content. |

Audiovisual Works

| Steamboat Willie | Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks | Cartoon | The first Mickey Mouse cartoon with synchronized sound, this animated short film marked a turning point in animation history and launched the iconic character of Mickey Mouse. |

| Plane Crazy | Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks | Cartoon | The first Mickey Mouse cartoon ever produced, though released later than Steamboat Willie, this silent film features Mickey and Minnie Mouse in a slapstick airplane adventure. |

Music

| Title | Author/Creator | Type of Work | Brief Description |

| Animal Crackers | Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby | Musical | This musical, starring the Marx Brothers, is a hilarious and entertaining spectacle. The show features witty dialogue, slapstick comedy, and memorable songs by Kalmar and Ruby. |

| Mack the Knife | Bertolt Brecht (lyrics) and Kurt Weill (music) | Song (from The Threepenny Opera) | This iconic song from The Threepenny Opera has become a standard in the world of music. Its cynical lyrics and memorable melody have made it a popular choice for singers and musicians across various genres. |

| Let's Do It (Let's Fall in Love) | Cole Porter | Song (from the musical Paris) | This classic Cole Porter song is known for its playful lyrics and sophisticated melody. The song's suggestive wordplay and catchy tune have made it a timeless favorite. |

| Sonny Boy | George Gard DeSylva, Lew Brown & Ray Henderson | Song (from the film The Singing Fool) | This popular song from the early days of sound film was a major hit for Al Jolson. The song's sentimental lyrics and Jolson's emotive performance resonated with audiences at the time. |

| When You're Smiling | Mark Fisher and Joe Goodwin (lyrics) and Larry Shay (music) | Song | This cheerful and optimistic song has become a standard and has been recorded by many artists. Its simple message of finding joy in life has made it an enduring favorite. |

| Empty Bed Blues | J. C. Johnson | Song | This blues song deals with themes of loneliness and lost love. The song's melancholic melody and heartfelt lyrics capture the pain of heartbreak. |

Sound Recordings

| Title | Author/Creator | Type of Work | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downhearted Blues | Bessie Smith and the Tennessee Ten | Sound Recording | This influential blues recording helped establish Bessie Smith as a major figure in the genre. It was a significant commercial success, selling millions of copies and showcasing Smith's powerful vocals and emotional delivery. |

| Bambalina | Ray Miller Orchestra | Sound Recording | This recording captures the vibrant jazz scene of the 1920s. The Ray Miller Orchestra's performance showcases the energy and improvisational spirit of early jazz music. |

| Charleston | James P. Johnson | Sound Recording | This recording features a classic example of the Charleston, a popular dance craze of the 1920s. James P. Johnson's piano playing captures the lively rhythm and syncopated beat of the Charleston. |

| Dipper Mouth Blues | King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, featuring Louis Armstrong | Sound Recording | This influential jazz recording showcases the talents of Louis Armstrong and King Oliver. The recording features Armstrong's innovative trumpet playing and Oliver's distinctive cornet style. |

| Down South Blues | Hannah Sylvester and The Virginians | Sound Recording | This recording is a notable example of early blues music. Hannah Sylvester's vocal performance and the accompanying musicians capture the raw emotion and soulful expression of the blues. |

| Froggie More | King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, featuring Louis Armstrong | Sound Recording | Another significant jazz recording from King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band. This recording further demonstrates the band's musical talent and their contribution to the development of jazz. |

| Lawdy, Lawdy Blues | Ida Cox | Sound Recording | This recording features a powerful vocal performance by blues singer Ida Cox. Cox's expressive voice and the song's emotional lyrics convey the hardships and resilience of Black life in the early 20th century. |

On January 1, 2025, works published in 1929 joined the public domain in the United States.

Literature

| Title | Author/Creator | Type of Work | Brief Description |

| A Farewell to Arms | Ernest Hemingway | Novel | Set during World War I, A Farewell to Arms tells the story of an American ambulance driver, Frederic Henry, and his passionate love affair with an English nurse, Catherine Barkley. Hemingway's concise prose and poignant depiction of war and love have made this novel an enduring classic. |

| The Sound and the Fury | William Faulkner | Novel | Considered one of Faulkner's most challenging and rewarding works, The Sound and the Fury portrays the decline of the Compson family through the fragmented perspectives of its four children. The novel's experimental use of stream-of-consciousness and its exploration of themes of time, memory, and loss make it a landmark of modernist literature. |

| Seven Dials Mystery | Agatha Christie | Mystery Novel | In this classic whodunit, Lady Eileen "Bundle" Brent, a young aristocrat with a knack for solving mysteries, finds herself entangled in a web of intrigue involving a series of murders and a secret society known as the Seven Dials. |

| All Quiet on the Western Front (first English translation) | Erich Maria Remarque (author) and Arthur Wesley Wheen (translator) | Novel | This powerful anti-war novel, originally published in German in 1928, offers a harrowing depiction of the horrors of World War I from the perspective of young German soldiers. The first English translation, by Arthur Wesley Wheen, became a bestseller and played a crucial role in shaping public perception of the war. |

| Rope | Patrick Hamilton | Crime Thriller Novel | This suspenseful novel revolves around two Oxford students who commit a murder and then host a dinner party with the victim's body hidden in a chest. The novel explores themes of morality, guilt, and the psychology of crime. |

| A Room of One's Own | Virginia Woolf | Essay | This extended essay, first published in 1929, is a feminist landmark that explores the challenges faced by women writers throughout history. Woolf argues that women need financial independence and a "room of one's own" to achieve their full creative potential. |

Comics

| Title | Author/Creator | Type of Work | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Popeye the Sailor | E. C. Segar | Comic Strip Character | Popeye the Sailor, the spinach-loving, one-eyed sailor man, first appeared in the comic strip "Thimble Theatre" in 1929. Known for his superhuman strength, quirky humor, and his love for Olive Oyl, Popeye has become a pop culture icon. |

The works listed above entered the public domain because their copyright protection has expired. In the United States, copyright law has evolved over time, and different rules apply to different types of works.

For works published or registered before 1978, the term of copyright generally lasts for 95 years from the date of publication. This is why works published in 1928 entered the public domain on January 1, 2024, and works published in 1929 entered on January 1, 2025.

However, sound recordings have different copyright rules. Audio recordings have a 100-year copyright term, compared to the 95 years for film, literature, and written musical compositions. Thus works published in 1924 expired at the start of 2025.

Furthermore, there are special cases for copyright expiry, particularly for works first published outside the U.S. These include unpublished works, works by foreign nationals, and works with specific publication conditions. These cases often involve complex legal considerations and may have different copyright durations.

The extension of copyright terms, such as those mandated by the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 (also known as the "Mickey Mouse Protection Act"), delayed many works from entering the public domain. This act extended copyright terms for works created after 1978 to the author's lifetime plus 70 years (up from 50 years), and for works created before 1978 to a total of 95 years. This act aligned U.S. law with European standards and responding to lobbying by industries reliant on long-term copyright protections, such as film and music.

For example, "Steamboat Willie" would have entered the public domain in 2004 under the previous law but was delayed until 2024 due to this extension. While copyright extensions protect the interests of creators and their heirs, they also postpone the cultural and creative benefits of public domain availability.

Public domain works are a valuable resource, as they can be used without permission or paying royalties. These works, free from copyright restrictions, can serve as the foundation for new creative endeavors and can be quoted extensively in various projects. Educators, for instance, can copy and distribute public domain works to classes or place them on course web pages without seeking permission or incurring royalty fees. Additionally, public domain works can be leveraged for commercial purposes, offering entrepreneurs and creators a wealth of material to incorporate into products and services.

However, while public domain material itself is free to use, it's essential to verify its public domain status before use. Compilations of public domain works may still be protected by copyright as “collective works,” meaning that copying and distributing an entire collection could infringe on the copyright of the compilation’s arrangement or curation. Users should exercise caution to ensure their use of such collections respects any existing copyright protections. By understanding these nuances, creators and educators can effectively utilize public domain resources while respecting copyright law.

To ensure compliance, always use reputable sources to confirm the public domain status of a work. Be mindful of copyright laws and regulations in your country, as rules can vary widely. While public domain material is free to use, collections of public domain works may be protected under copyright as “collective works.” Copying and distributing an entire collection without authorization could infringe on the collection’s copyright, even if the individual works are not protected.

Finally, when using public domain works, act responsibly by giving credit to original creators whenever possible, promoting ethical use of these cultural treasures.

Derivative works are new creations based on public domain works, and they can be protected by copyright law. These works may include adaptations, sequels, or reinterpretations of existing public domain content. For example, an updated film adaptation of a public domain novel could qualify as a derivative work. If you create any derivative work, consider registering your work with the copyright office to secure copyright protection. Copyright registration provides many advantages and protections against unauthorized use of your derivative work. Derivative works are worthy of protection against copyright infringement.

The copyright owner of a derivative work is granted exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, and display their unique contributions to the original material. However, this protection only applies to the new creative elements added by the author, not the underlying public domain work itself.

Derivative works play a crucial role in enriching the cultural landscape by breathing new life into public domain works. Through reinterpretation and adaptation, creators can engage modern audiences while contributing innovative ideas to the artistic and literary world.

As copyright terms expire, each new year brings a fresh infusion of artistic and intellectual treasures for the public to enjoy and reinterpret. Understanding the dynamics of copyright and the public domain empowers creators, scholars, and enthusiasts to leverage these resources responsibly and innovatively. If you need assistance with evaluating works for their public domain status, need assistance with pursuing copyright registration, or need assistance with other issues related to copyrights, please contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

Need to protect your business name or logo within California? This article outlines the California state trademark registration process, including its legal framework, benefits, and the steps required to successfully protect your trademark rights. It also highlights practical considerations, such as conducting a thorough search, selecting the correct classification, and handling the registration process. Whether you’re a new entrepreneur or an established business, understanding state trademarks is necessary to enable you to protect your business and brand.

Trademarks are a form of intellectual property that protects the source of a particular good or service from imitators that would either intentionally or unknowingly trade on the reputation associated with the source of goods or services (the trademark owner). A California state trademark is specifically designed for local businesses that operate solely within the state. Unlike federal trademarks, which provide nationwide protection, California state trademarks are limited to the geographical boundaries of California. This type of trademark serves as a powerful tool for identifying and distinguishing products or services within the local market.

Registering a California trademark offers significant legal protections against unauthorized use by competitors within the state. For many California businesses, especially those that focus on local commerce, state trademarks provide a cost-effective way to secure their brand identity.

Moreover, the California Trademark Unit manages registrations for specific types of trademarks, including container brands and estate names, ensuring a tailored approach for different business needs. While state trademarks are not as far-reaching as federal trademarks, they still offer robust protections and can be a crucial asset for businesses operating within California.

The legal framework for California state trademarks is outlined in the Model State Trademark Law under California Business and Professions Code Sections 14200-14272. These laws provide the foundation for trademark rights and protections within the state. While rights to a trademark arise from its use in commerce, registering the trademark is governed by the CBP code, which provides additional legal protections and formal recognition.

Registering a California state trademark comes with a host of benefits that can significantly impact your business. The costs are lower. With a state registration fee paid to the California Secretary of State's office is $70, considerably less than the approximately $350 filing fee for federal registration. There is also a simpler application process than at the federal level. The application is examined by the California Trademark Unit for formalities, such as descriptiveness, specimen of use, and properly identified goods. There is no in-depth search for confusingly similar marks. If the exact mark is not previously registered with the state, then it is very likely that you will be able to register the mark if the formal requirements are met. Thus, if you have engaged a trademark attorney to handle the application, the attorney's fees will be significantly less for a California trademark application because there is generally less to do in the examination process. The process of state trademark registration is straightforward and less cumbersome compared to the federal registration process, making it a lower cost option for businesses focused on local commerce.

The registration process for a California trademark is generally faster than for federal trademarks. Often completed within weeks, this quicker turnaround means businesses can secure their trademarks and start reaping the benefits much sooner. Once registered, your trademark becomes a matter of public record, enhancing your brand’s visibility, and providing a formal record of your claim of ownership.

Another significant benefit is the exclusive rights to use the trademark within California. This exclusivity helps prevent competitors within the state from using similar marks, thereby protecting your brand’s identity and market position.

Registering a California state trademark involves several steps, including conducting a thorough trademark search, preparing a proper specimen of use, correctly identifying the classification of goods, and correctly filling out and submitting the application forms to the California Secretary of State. Each of these steps is essential for successfully registering a trademark in California, which are discussed in more detail below.

Before you can register a trademark in California, it is important to conduct a thorough trademark search. This step ensures that your proposed trademark is not confusing to other similar trademarks registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) or that are otherwise in use by third parties and thus does not infringe on the rights of others. It is not enough to simply use the California Secretary of State’s trademark search tool. This only tells you whether your mark has been registered with the state. Most registered trademarks and service marks in use in California are either federally registered or unregistered. In order to avoid potential conflicts, your trademark search needs to be broader than just the California state trademark search tool. We recommend seeking the assistance of an experienced trademark attorney to properly vet your trademark or service mark before you file a trademark application. You do not want to waste your funds on an application that is invalid and that creates a public record that you are engaging in trademark infringement.

Selecting the correct classification is absolutely necessary for the registration process. Trademarks are categorized based on the goods or services on which they are used. A trademark protects goods, whereas a service mark is specifically designed to protect services. Goods and services are classified separately based on their relatedness. There are 45 classifications set by the United States Patent and Trademark Office that the Secretary of State's office has adopted. If you mark is used on different types of goods and/or services, your trademark application may include multiple classifications. Choosing the wrong class can result in the inability to register your trademark. Each classification for which you seek registration comes with a $70 filing fee. Carefully reviewing the classifications and selecting the one that best fits your business’s goods or services is critical.

Preparing your California trademark application involves several key steps. The primary form used for this process is the TM-100. You must have begun use of your trademark before you can seek a trademark registration in California. California Business Professions Code Section 14207 requires that a trademark must be in use and a specimen of such use must be submitted in the application before a California trademark registration can be issued. This contrasts with the federal trademark registration process, in which you can file an intent-to-use application if you a bona fide intent to use trademark or service mark in the future.

The specimen of use is required to demonstrate how the trademark is being used. This can include photos of the product, marketing materials, or screenshots of your website. Your application may need a particular type of specimen depending on the nature of your goods or services.

There are a number of other formal requirements in the application, including the date on which actual use of the trademark began, the designated owner of the mark (you personally or your business entity), and a declaration that the applicant is the owner and that the applicant is not aware of any third party that has a registered mark or the right to use a mark that is confusingly similar to the applied-for mark. You must provide accurate details about your trademark and declare the truthfulness of this information under the risk of criminal penalties for false statements under the California Business and Professions code.

Once your application is prepared, you can file it with the secretary of state’s office. This can be done online through the California Secretary of State Bizfile Portal, in person at the Sacramento office of the Secretary of State, or by mail. The date of receipt of your application establishes its priority as of the date and time of the submission, so timely submission is crucial.

Declaring the accuracy of your application details is important, as false statements can result in penalties of up to $10,000. Because there are significant legal implications in the filing the trademark or service mark application, it is highly recommended that you seek the assistance of an attorney before filing the application.

During the registration process, you may receive an office action—a notice from the Secretary of State's office about issues with your application, which are limited to formal issues. Responding promptly and accurately to these office actions is essential, as failing to do so can result in your application being abandoned.

The issues raised in such office actions almost invariably regard compliance with the requirements of section 14207 of the California Business and Professions Code. They are not complicated issues, but they can be difficult for the layperson to address. Seeking guidance from a licensed California trademark attorney can greatly increase your chances of success. Additional fees may be incurred, but you will likely succeed in registering your mark with proper assistance.

After successfully addressing any office actions, your registration may issue. The process usually lasts no more than a few weeks before you receive your registration certificate, officially marking your trademark as registered in California. Subsequently, you will be required to maintain the registration by filing renewal applications every five years.

Maintaining your California state trademark requires an ongoing effort. Registrations are valid for five years and must be renewed to remain active. Renewal involves submitting the necessary documentation to demonstrate the ongoing use of the trademark in commerce.

Failing to renew your trademark on time can lead to its cancellation, requiring a complete reapplication process. Continuous commercial use is crucial to avoid abandonment and maintain your trademark rights.

Additionally, monitoring your trademark to prevent unauthorized use by competitors is essential for long-term brand protection. If you allow third parties to use confusingly similar trademarks without taking action, you will lose exclusivity and your trademark rights will be eroded. If your brand has value it is important to police the marketplace for unauthorized use and enforce your trademark rights when necessary.

Registering cannabis-related trademarks in California is possible, which contrasts with federal trademark law and policy. This allows businesses in the cannabis industry to protect their brands within the state, despite federal limitations.

However, cannabis-related trademark registrations and the legal implications of such filings are delicate topics and should be approached with caution. It should be remembered that cannabis is still outlawed under the federal Controlled Substances Act. Consulting with a trademark attorney who specializes in this area can provide valuable guidance and ensure compliance with state regulations.

Understanding the difference between the TM and ® symbols is crucial for trademark owners. In California, you can use the TM symbol to indicate that you claim rights to your trademark, even if it is not federally registered.

The ® symbol can only be used after your trademark is federally registered. Only a federal trademark registration allows for the use of the ® symbol.

Registering a state trademark in California offers specific advantages for many businesses. If your business operates solely within California, federal registration may not be an option. However, a state trademark provides significant protections. Additionally, state registration often involves fewer restrictions and a quicker, more affordable process.

State trademarks are particularly beneficial for businesses involved in industries like cannabis, where federal registration may not be feasible. A California state trademark also provided protections under California law in addition to applicable sections of the Lanham Act (federal trademark law) and provides a public record of your trademark rights within the state.

Registering a California state trademark is a strategic move for businesses operating within the state. It offers cost-effective, robust legal protections and enhances brand visibility. To register a California state trademark, businesses must use the mark in commerce, conduct a thorough trademark search, and correctly prepare the application and navigate the application process. The benefits of a California state trademark extend beyond legal protection; they reinforce your brand’s presence and value within the local market.

If you are considering pursuing a trademark registration, contact our office for a free consultation regarding trademark registration.

© 2024 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

Business owners often hire independent contractors (e.g., graphic designers, marketing firms, web designers, etc.) to assist with marketing and ad design, website design work, branding concepts, content writing, product photography, and many other projects and tasks that require creativity. Many businesses are not aware that they do not own the copyrights in the work provided by these independent contractors. The copyrights in such creative works only transfer to the business owner if there is a written contract that expressly includes a proper assignment clause. Without this, the business owner has only an implied license to use the work generated by the independent contractor ("IC"). The terms of this license are not defined and open to interpretation and dispute between the IC and the business. The business cannot transfer the copyrights (e.g., if the business or brand is sold) and may not be able to transfer the license. Business owners need to understand their intellectual property and manage it proactively. There are pitfalls for the unwary. The bottom line is that you as a business owner need to be the copyright owner of the work that you pay for.

A copyright assignment is an agreement that transfers ownership from the original creator to another party in exchange for some payment or other consideration (any bargained-for value provided by the receiving party), which grants the new owner rights to the work. This article will explain what a copyright assignment entails, its legal requirements, and how it differs from ‘work for hire’.

A copyright assignment is a legal agreement that transfers ownership rights from the original creator to another individual or entity. The assignment can transfer to the assignee all or some of the exclusive rights in the work to use, modify, and distribute the work. Copyrights are a bundle of rights granted to the creator of an original work. These rights include the ability to perform or display the work publicly, reproduce the work (e.g., by printing, copying digital files, scanning, etc.), distribute copies of the work (e.g., by posting the work on social media, selling printed copies, transferring digital files, etc.), create derivative works, and license or assign these rights to others. Each of these rights is distinct, meaning they can be transferred, licensed, or assigned individually or collectively. An assignment can be written to transfer one or more rights in this bundle to another party. The assignment can encompass all rights or just specific ones, depending on the agreement. The original creator relinquishes control of whatever rights are assigned and cannot exercise the assigned copyrights in the work without permission from the assignee. For example, an author of a novel might assign the right to publicly perform the work to a theater company while retaining the rights to reproduce and distribute copies of the book. The author has relinquished the public performance rights and can no longer pursue public performances of his work, but retains the right to sell the book.

Publishers and businesses must have control over the copyrights in works they commission because it enables them to transact business with respect to the work without limitations and it makes the work an asset in the business, rather than just something the company is allowed to use. Complete control over a work is ideal to allow the business to maximize its commercial potential. However, in certain situations like the example above, carve outs for the original author may make sense. Each situation is different and requires a skilled copyright attorney to avoid costly mistakes.

For a copyright assignment to be valid, it must be executed in writing. Notarization is advisable, but not required. The written agreement should clearly outline the transfer of ownership and the specific rights being assigned. The agreement should also detail the amount of consideration. A copyright assignment is not valid without "consideration", which is anything for which the author is willing to exchange the copyrights. In other words, there must be a bargained-for exchange. Where a business is engaging an IC, the assignment is part of the bargain upfront and the consideration is in the price paid for the work. However, if the business fails to include the assignment the original agreement, there must be separate consideration for the assignment - i.e., the business has to pay the IC again to get a valid transfer of the copyrights. This is a mistake businesses make very often.

In order to avoid these mistakes, businesses should take a proactive approach similar to that outlined below.

Assigning copyright requires several critical steps: drafting a comprehensive agreement with the IC upfront, obtaining signatures, registering the copyrights in the work with the US Copyright Office (USCO), and recording the assignment with the USCO. The copyrights should be registered to create a public record of the work. The assignment should also be recorded with the USCO to establish a public record of the assignee's rights. Clarity in the scope and terms of the rights being transferred helps prevent misunderstandings and disputes. These steps can be adopted as a structured process for a business to execute any time they are soliciting creative services from an IC. Such a process can ensure that both the creators and assignees understand the terms of the engagement and that the copyrights are being transferred, and that there is a legally sound transfer of the copyrights.

A copyright assignment agreement should be comprehensive and include essential clauses to facilitate the transfer. Improper handling of copyright assignments, like omitting critical clauses, can impact your ability to enforce the copyrights. Careful drafting and review of the agreement are crucial to protect both parties’ interests. Having a copyright lawyer draft such an agreement is advised to ensure it is properly structured and legally sound. The original author (IC) must sign the agreement for it to be legally binding.

Essential elements of a copyright assignment agreement include the grant of rights, term and termination conditions, payment and consideration terms, the scope of the assignment, and warranties. The scope of the assignment may vary depending on the agreement of the parties. Copyrights are not monolithic. There are a bundle of copyrights in a work. There are several aspects of copyrights and the agreement should be explicit about which rights are being transferred and which rights are being retained by the IC, if any. For example, a graphic designer may demand that they are granted a license to use a copy of their work for inclusion in their public portfolio and/or other advertising.

The terms of the assignment should be tailored to the specific transaction and failure to properly capture the parties' intent and the necessary language can result in a failed transfer or unintended limitations on the transfer of rights.

In order to publicly record copyrights in a particular work, the work must be registered with the USCO. To register a copyright, the applicant must complete an application, providing the title of the work, identifying the author(s), its creation date, and whether and when it was previously published, such as by sale, public performance or display of the work. A deposit of the work must also be submitted. Additionally, groups of related works, such as a group of photographs, can sometimes be registered together under specific rules. Copyright registration ensures legal protection if the work is displayed, copied, or performed by any person or group without authorization. Once registered, there is a public record of the copyrights in the work and the copyrights can be enforced against infringements by filing a complaint in federal court. Registration also establishes constructive notice of the work to the public, meaning that even if a copyright infringement occurs without actual knowledge of the copyrighted work, the infringer is still liable. Copyright notice can be used to provide actual notice of copyrights to potential infringers, but registration provides more complete copyright notice benefits.

Recording the copyright assignment with the Copyright Office establishes public notice and legal recognition of the transfer of the copyrights from the author(s) to the assignee. The Copyright Office does not provide specific forms for copyright transfers but accepts various documents related to copyright ownership and maintains records of submitted assignments. This step solidifies the legal validity of the assignment and a pubic record of the transfer to the assignee. The publicly recorded assignment is crucial for future reference and resolving potential disputes over ownership.

One common pitfall in engaging an IC for creative services is to assume that because you are paying the IC for the work, you own the copyrights. As explained above, this is incorrect. There must be a written assignment signed by the IC that expressly transfers the copyrights to you.

Another common mistake is the use of a copyright assignment form found online. Copyright assignments are unique to each situation. It is important that the assignment is appropriately tailored to the situation by an attorney. A inadequate copyright assignment can lead to legal disputes over ownership, costly litigation, and complicate future licensing deals.

Failing to keep adequate records of copyright transfers can be equally damaging. The copyright office database does not provide copies of the copyrighted work associated with registration or assignment records. Thus, a failure to keep copyright registration and assignment records associated with copyrighted work can lead to confusion about what copyrights you own and associated enforcement and licensing problems.

These potential consequences underscore the importance of following proper procedures and maintaining accurate records to protect one’s interests.

While both copyright assignment and work for hire involve the transfer of copyright ownership, they operate very differently. A copyright assignment can be made between any two parties, whereas a work for hire is only created either by an employee or by an IC under specific circumstances. For a work to qualify as work for hire, it must either be created by an employee as part of their normal responsibilities and job duties or fit into one of nine specific categories defined by law. These categories include commissioned works such as translations, instructional texts, and tests, among others. Additionally, the work must be specially ordered or commissioned, and there must be a written agreement stating that the work is a work for hire.

Many businesses operate under the assumption that creative work specifically commissioned for the business is a "work for hire". However, as a general rule, the creative work is not a work for hire, since the categories of works for hire are fairly narrow and there must be a written agreement specifically identifying the work as a work for hire. It is much more effective to include specific assignment language for each contract made for creative services.

In summary, a copyright assignment is essential in any situation where you are engaging an IC to create artistic, design, decorative, or other kinds of creative work. You must include assignment language in the initial contract, clearly define the scope of the assignment, maintain accurate copyright records, and ideally register the copyrights with the USCO. Proper management of copyright assignments allows creators to retain control over their work and businesses to fully exploit their commercial potential.

Your copyrights are important assets and should be protected. Our attorneys have decades of experience in the copyright field. Contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2024 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.