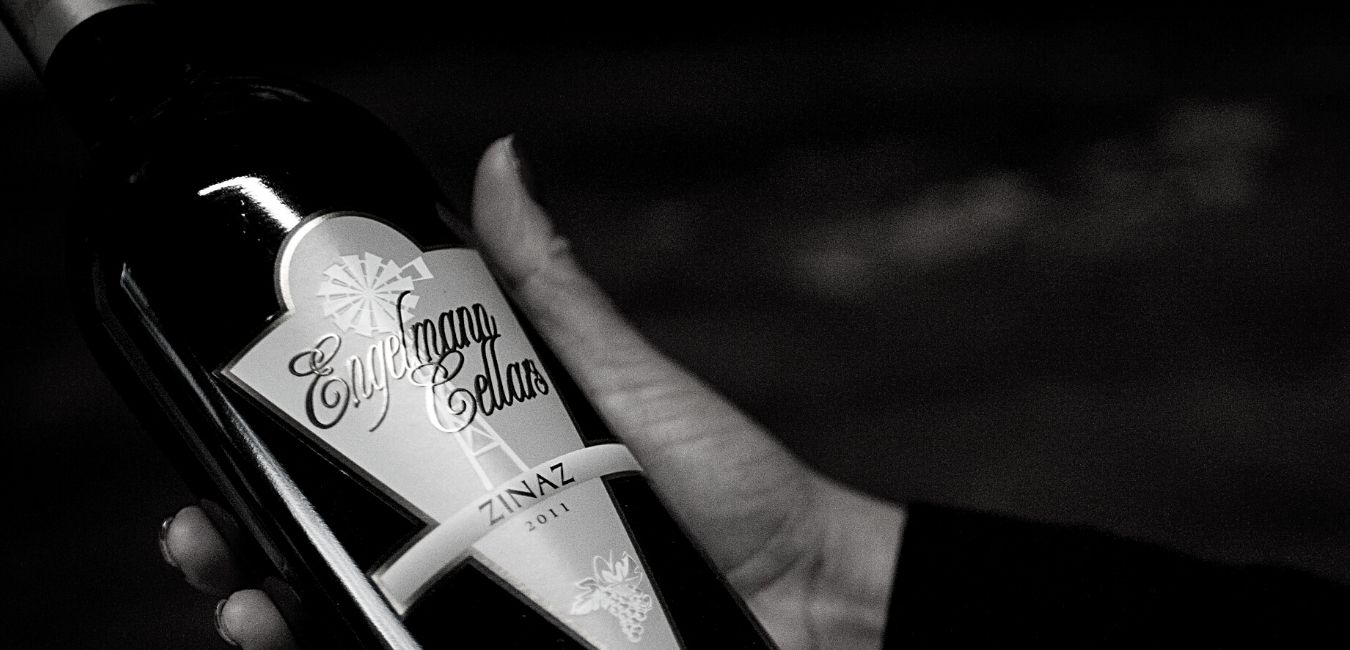

A common law trademark is established through the actual use of a mark in commerce rather than by formal federal trademark registration through United States Patent and Trademark Office. In other words, common law trademark rights are established by opening a business and providing goods and services to consumers under a business name or brand - e.g., opening a donut shop called Dawn's Donuts and selling donuts to customers. Business names, logos, and phrases that are regularly used can be considered common law trademarks. In the United States, common law trademark rights are acquired by being the first to use the mark in connection with goods or services in a particular geographic area. These are unregistered trademarks that still carry rights recognized by the state and federal courts and can be enforced against others who subsequently use a confusingly similar mark in the same area.

To establish common law trademark rights, you must use the trademark in commerce. This process begins when a business or individual uses a distinctive mark to identify their goods or services and distinguish them from those of others. The key factors in establishing these rights are distinctiveness, use, and recognition in the marketplace.

The mark must be actively used in the sale or advertising of goods or services. This use must be bona fide and not merely token or for the purpose of reserving a right in the mark. Proof of use, such as sales receipts, advertisements, and other business documents, can support a claim of common law rights. Common law trademarks underscore the principle that trademark rights arise from actual use, not merely from registration.

Recognition in the marketplace is also crucial. The mark must become associated with the goods or services in the minds of consumers in the area where it is used. Distinctiveness means the mark must be unique enough to identify the source of the goods or services. Offering a common service with a bland name, rather than a brand name, is not distinctive and will not garner consumer recognition. For example, if you open a mechanic shop called Downtown Mechanics, your mark will not establish strong consumer recognition or strong trademark rights. However, if you name a fun name like Grease Monkeys, it will be much more memorable and distinct in the mind of the consumer. In order to have enforceable trademark rights, the mark must be distinctive.

Generic terms and descriptive terms should be avoided because they provide little to no trademark rights. For example, if you name your bakery "pastry shop", the name describes exactly the business services, and is thus generic. A name like Tasty Bakery would be considered descriptive because "tasty" is descriptive of the pastry offerings in the bakery.

If the foregoing requirements are satisfied, the user of the trademark can claim common law trademark rights, which provide legal grounds to prevent others from using confusingly similar marks within the same geographic area where the trademark is used, thus protecting the goodwill and reputation associated with the mark.

Exclusive Use in the Geographic Area: Common law trademark rights grant the holder exclusive rights to use the mark within the geographic area where the trademark is being used and has acquired distinctiveness amongst consumers. This means the trademark holder can prevent others from using a confusingly similar mark within that specific market area.

Right to Prevent Confusion: The trademark owner can prevent others from using a trademark or service mark that is likely to cause confusion among consumers as to the source of the goods or services. This protection helps maintain the trademark's goodwill and ensures that customers are not misled.

Right to Bring Infringement Claims: Common law trademark owners can bring infringement claims under state law. Many states have statutes and common law principles that provide remedies for trademark infringement, including injunctions, damages, and sometimes attorney's fees. The specific remedies available depend on the state's laws.

Federal Lanham Act Claims: While common law rights are primarily protected under state law, trademark holders can also bring claims under the federal Lanham Act. Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act provides a cause of action for false designation of origin, which can be used to address unfair competition and infringement of unregistered marks. This federal cause of action allows common law trademark owners to seek relief in federal court, providing broader enforcement options.

Unfair Competition Claims: Common law trademark rights can be the basis for bringing unfair competition claims because they protect the goodwill associated with a trademark used in commerce. If another party uses a confusingly similar mark, it can mislead consumers and harm the original trademark holder's reputation and business. Such unauthorized use can be considered unfair competition, as it takes advantage of the established market presence and consumer recognition of the original mark.

A common law trademark has limitations and disadvantages in comparison to a federally registered trademark. Unlike federally registered marks, unregistered marks do not provide nationwide protection or the benefits associated with federal registration, such as a presumption of validity and the potential to recover treble damages and attorney's fees. These limitations can significantly affect the scope and enforceability of trademark rights.

Limited Geographic Scope: One of the primary disadvantages of common law trademarks is their limited geographic scope. Common law rights are generally confined to the area where the mark has been used and gained recognition. This means the trademark holder does not have exclusive rights to the mark outside of this area. In contrast, federally registered marks grant nationwide protection, allowing the owner to enforce their rights across the entire United States, regardless of the specific areas of use.

Lack of Presumptive Rights: A federally registered marks provide presumptive evidence of the trademark's validity, ownership, and the exclusive right to use the mark in commerce on a national scale. This presumption can be crucial in legal disputes, making it easier for the trademark owner to prove their case. Common law trademarks do not offer these presumptions, requiring the owner to provide more extensive evidence of their rights and the mark's distinctiveness and market presence.

Reduced Enforcement Mechanisms: Enforcing common law trademark rights can be more challenging and costly. While a common law trademark holder can bring infringement actions under state laws and unfair competition claims under the Lanham Act, they are not able to bring trademark infringement claims under 15 U.S.C. § 1114, claims for statutory damages for counterfeiting, claims for enhanced damages for Willful Infringement, or dilution claims without a federal registration. Federal trademarks provide these enforcement mechanisms to trademark owners and provide an advantage over common law trademark holders.

Notice and Deterrence: Federal registration places the trademark in the official records of the US Patent and Trademark Office, providing constructive notice to others of the mark's existence. This can deter potential infringers who conduct trademark searches before adopting a new mark. Common law trademarks do not benefit from this official notice, making it more likely that others might inadvertently use a similar mark, leading to potential conflicts.

Incontestable Trademark Registration: An incontestable trademark registration is a federal trademark that has been registered and continuously used in commerce for at least five years with no adverse decisions or pending legal challenges to the owner's trademark rights. Incontestable status provides conclusive evidence of the trademark's validity, the registrant’s ownership, and the exclusive right to use the mark in commerce. This makes it significantly easier for the owner to enforce their rights in legal proceedings and avoid challenges to their rights. An incontestable trademark can only be challenged on very limited grounds, such as the mark becoming generic, fraud in obtaining the registration, or abandonment. This provides a strong defense against attempts to cancel the trademark, offering greater security and stability for the owner of an incontestable federal trademark.

Use of the ® Symbol and Constructive Notice: The Lanham Act permits only federally registered trademarks to use the registered trademark symbol ®. This symbol provides public notice of the registration and can act as a deterrent against infringement. Common law trademarks can use "TM" or "SM," but these symbols do not result in the constructive nationwide notice that the registered trademark symbol provides. Using the ® symbol provides the owner of the trademark nationwide notice of their rights. Constructive notice is a legal concept under which all persons in the US are deemed to be on notice of the federal when the symbol is applied to the registered goods or on the promotional materials for the registered goods or services (e.g., website, advertisements, product/service literature, etc.). The ® symbol should be displayed prominently alongside the registered trademark, typically in the upper right-hand corner, lower right-hand corner, or immediately following the mark. Constructive notice eliminates the defense of "innocent infringement." An alleged infringer cannot claim that they were unaware of the trademark existence or its registration status and may be liable for damages from the point of their initial use of the trademark.

Federally registered trademarks can serve as a basis for seeking foreign trademark registrations in other countries under international treaties, such as the Madrid Protocol. Common law trademarks do not offer this advantage, making it more difficult and expensive to secure international trademark protection.

Common law trademarks offer certain protections, but they are inferior to the rights provided by a federal registrations, which provide broader, more robust, and more easily enforceable rights that can be crucial for maintaining and defending a brand. A state trademark registration may also be available through the state's Secretary of State's office. However, state trademark registrations typically have significantly fewer protections than a federal registrations, and they do not have nationwide reach.

It should be noted that a federal trademark application cannot be submitted for some unregistered trademarks. There are specific criteria and requirements that must be met in order to register your trademark. The primary reasons why a common law mark may not qualify for federal registration:

To be eligible for federal registration, a trademark must be used in interstate commerce, meaning it must be used in connection with goods or services that are sold, transported, or promoted across state lines or that otherwise have an impact on interstate commerce. This is a requirement because the constitutional authority for the USPTO to issue trademark registrations is based on the federal government power to regulate commerce between the states. This use in commerce requirement is not black and white. There is quite a bit of nuance in this interpretation of this requirement. For example, a restaurant located in one state only operates in that state. However, if is located on the interstate highway, for example, it likely serves many interstate travelers and "affects" interstate commerce. Such a restaurant would likely be able to properly file a federal trademark application to register its name.

Generic Marks: Marks that are generic and directly describe the product or service itself cannot be registered.

Descriptive Marks: Marks that are merely descriptive of the goods or services are also generally not registrable unless they have acquired secondary meaning. For example, "CREAMY" for yogurt would be considered descriptive and not inherently distinctive.

Immoral or scandalous marks that consist of immoral, deceptive, or scandalous matter, or that disparage individuals or groups, are not registrable. Although this criterion has been subject to legal challenges, it remains a consideration for the USPTO.

If your mark is eligible, you should register your trademark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The benefits of a federal trademark registration far exceed the costs of obtaining and maintaining the registration. If your business is successful, you want exclusive rights in your business name and/or brand name. The exclusivity provides strength to the brand and allows your to build your reputation with your customers without consumer confusion with copycat brands or competitors.

The process of pursuing a trademark registration should begin with finding an experienced trademark attorney. Many attorneys are willing to file federal trademark applications because it is an apparently simple process. However, the skill is not applied in the filling of federal application forms. The experienced trademark attorney conducts due diligence in advance of the application to determine the strength of the mark, potential infringement issues, and whether there are any potential infringers. A trademark search is essential for this process. The trademark search should include an examination of both the federal register (the database of registered marks) and unregistered use of similar marks (a common law trademark search). The common law trademark search is a complicated process that requires the skill and expertise of experienced professionals. The trademark search is the foundation on which your trademark protection is built and it should not be taken lightly. Ideally the search is conducted before you adopt and commit to a mark.

Once the search is complete, the trademark attorney will assist with the proper filing of the trademark application, making sure that a proper specimen is filed, that the goods or services are properly identified, that the filing strategy for the mark or marks is optimized, and that all formalities are observed. These steps are critical to successfully file applications to register your trademark.

If you are able to properly pursue a trademark registration you should. A common law trademark carries some enforceable rights and protections, but they are inferior to those of a trademark registration. If you are planning to start a business or brand, you should contact an attorney that specializes in this area of intellectual property law. They can help you with selecting a proper mark that can be an asset to your business on which you build your reputation and relationship with consumers. You do not want the mark you initially select to become a liability. Facing infringement claims and/or having to involuntarily change your mark down the road can be a major disruption.

A trademark is a symbol, word or phrase, graphical design, sound, color, video clip, or a combination thereof that distinguishes your products or services from those offered by others. A trademark serves to uniquely identify your brand for the benefit of your customers. A trademark is a type of intellectual property (IP) that identifies a business or product. A trademark registration protects and expands your exclusive rights in your trademark. The process of applying for a trademark involves understanding who is eligible to file an application. This article delves into the various types of applicants and entities that can properly apply for trademark registration through the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Various forms of businesses can own a trademark and apply for a trademark registration, including individuals, partnerships, corporations, limited liability companies (LLCs), clubs, trusts, and non-profits. However, there are other requirements that must be met in order to be a proper applicant for a trademark registration, as discussed below.

According to 15 U.S.C. § 1051(a)(1) and (b)(1), an application to register a mark must be filed by the owner of the trademark under two filing options: actual use and intended use applications. Trademark rights can be established through actual use in commerce prior to filing a trademark application. This involves using the mark on goods or services in a manner that distinguishes them from those offered by others, thereby creating a connection in the minds of consumers between the mark and the source of the goods or services. A business can establish rights through continuous and consistent use of the mark, which builds the recognition and goodwill in the mark and the business. However, relying on common law trademark rights can be problematic because these rights are limited to the geographic area where the mark is actually used, which can restrict the owner's ability to enforce the trademark in other areas. Additionally, common law rights offer less legal protection compared to a registered trademark, making it more challenging to prevent others from using a similar mark. The lack of a formal registration also means the owner must prove the existence and scope of their rights in any legal disputes, which can be both time-consuming and costly. Finally, common law rights do not provide the benefits of federal registration, which provides several advantages over common law trademark rights, including a legal presumption of ownership and nationwide notice of your trademark rights.

If a business or entrepreneur wishes to secure rights in a trademark, but has not yet begun using the mark in connection with any goods or services, an application may still be filed if certain conditions are met. An intent-to-use application may be filed if the applicant has a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce. This means that the applicant has genuine plans to use the mark in connection with their goods or services in the near future. This intent must be real and not merely a token gesture to reserve the mark. Evidence of such intent might include business plans, marketing preparations, or product development efforts that demonstrate a serious intention to bring the mark into commercial use. The requirement ensures that the trademark system is not clogged with marks that applicants do not intend to use, maintaining the integrity of the trademark registry.

If an applicant is improperly identified in a trademark application, the application may be deemed void ab initio, meaning it is invalid from the outset. This can occur if the application is filed by a person or entity that does not have the legal right to claim ownership of the mark, such as someone who is not the actual trademark owner or lacks a bona fide intent to use the mark in commerce. It cannot be amended to correct the applicant because the applicant has no transferable rights in the application. See 37 C.F.R. § 2.71(d). Because an improperly identified applicant cannot simply amend the application to correct the error, a new application must be filed resulting in the loss of the original filing date. This delay can potentially lead to the loss of priority if another party files for the same or a similar mark in the interim. Also, the applicant faces the additional costs associated with refiling and the potential for increased legal complications.

A proper trademark application and the resulting registration allows a trademark owner to sue for trademark infringement in state or federal court. Trademark ownership also secures the owner's trademark rights on a nationwide basis. Thus, correctly filing a trademark application with the correct applicant is critical to the health of your brand.

Under US trademark law, applicants for trademark registration can be natural persons or juristic entities. Juristic entities include partnerships, joint ventures, associations, unions, corporations, and other organizations capable of suing and being sued in court. See 15 U.S.C § 1127. An application for a trademark registration cannot be filed under a subunit of a corporation or under a fictitious business name (a "DBA") because they are not legal entities that can sue or be sued.

Organizations and juristic entities can file trademark applications to secure trademark registration and protect their intellectual property rights. Various types of business entities are eligible to apply, each with particular requirements:

Countries, states, cities, and other related types of governmental bodies can apply to register marks with some restrictions. Governmental bodies can seek a trademark registration to protect their unique identifiers, logos, and names from unauthorized use, ensuring that the public can trust the source and quality of the services or goods associated with them. This protection helps maintain the integrity and reputation of governmental programs and initiatives. For a governmental body to file a trademark application, it must be the trademark owner and it operate under governmental authorization. The application must specify the governmental entity's legal status, such as "an agency of the United States" or "a municipal corporation organized under the laws of [state]."

Two famous examples of trademarks registered to the US government:

It is worth noting that Section 2(b) of the Lanham Act prohibits the registration of any mark that consists of or comprises the flag, coat of arms, or other insignia of the United States, any state, municipality, or any foreign nation, or any simulation thereof. For example, the U.S. flag cannot be registered as a trademark. In the case In re The Government of the District of Columbia, 101 USPQ2d 1588 (TTAB 2012), the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) affirmed the PTO's refusal to register the official seal of the District of Columbia. The refusal was based on the ground that the seal, intended for use on various goods such as clocks, cufflinks, memo pads, pens, pencils, cups, mugs, and clothing, constituted a governmental insignia barred from registration under Section 2(b). The decision confirmed that the District of Columbia qualifies as a “municipality” under the statute, and there was no dispute that the applied-for mark was the official seal of D.C.

Federal trademark law may allow a minor to file an application, depending on law of the state of the minor's residence. If a minor can lawfully form contracts and can participate in legal proceedings in the state of their domicile, the minor can file a trademark application in their own name. If not, the application must (1) be filed in the name of a parent or legal guardian and (2) indicate their status as parent or legal guardian of the minor. If the named applicant is a minor, the examining attorney must investigate whether the minor qualifies as a proper applicant under the applicable trademark law.

A licensed trademark attorney can file a trademark application on behalf of a client who is a proper trademark applicant by following specific procedures and requirements set forth by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). First, the attorney must engage the client and get a power of attorney from the client to file the trademark application. The attorney must then meet and confer with the client to gather the necessary information.

As initial step, the attorney must ensure that the client qualifies as a proper trademark applicant, as outlined above. The attorney also gathers other essential information from the client, such as the applicant's legal name, entity type, and address. The attorney also needs details about the trademark, including the mark itself, a clear description of the goods and services associated with the mark, and the basis for filing (e.g., current use in commerce or intent to use).

Throughout the entire process, the attorney communicates with the USPTO, responds to office actions, and ensures all legal requirements are met. This professional guidance helps streamline the application process and increases the likelihood of successful trademark registration, safeguarding the client's intellectual property rights.

Today, trademark applications are filed through the Trademark Electronic Application System (TEAS), which provides a streamlined submission process and an efficient trademarking process. The application must properly identify not only the applicant, but also the trademark or service mark and the goods or services. There are 45 different trademark classes, and you can register your mark in multiple classes if necessary. Your goods and services may fall into different trademark classes, and the correct classification for your goods or services should be determined prior to filing in order to avoid rejections and delays in the trademark examination process. Each trademark class in the application carries filing fees of $350.

Once the application is filed, you have established a priority date and effective date for your exclusive right to the trademark, assuming that you are the earliest adopter and exclusive user of the mark in connection with your goods and/or services at the time of filing. It is worth noting here that due diligence should be conducted before filing the trademark application to determine whether there are any third party rights in the same or similar mark that may impact your rights. A thorough trademark search of trademark filings with the USPTO and existing unregistered trademark use should be conducted before filing a trademark application to ensure your mark is unique and that you have substantially exclusive rights in your mark.

Once your trademark application is filed, you will receive a filing receipt and you will have established a public record of your claim to trademark rights. The filing date establishes your rights nationwide to your trademark filing, assuming that your mark is registrable and there is no confusingly similar use of the mark at the time the application is filed. This nationwide protection of your mark provides continuing protection as your business grows and expands geographically.

The trademark application process typically takes several months to a year or more to complete. The application will be in a queue at the US Patent and Trademark Office for several months before a trademark examiner begins to examine the application. The trademark examiner will review your application to ensure it meets the requirements for registration. The examiner assesses whether the mark is distinctive and not merely descriptive of the goods or services. The goods or services identified in the application must be clearly defined and associated with the mark. Additionally, the examiner checks for any likelihood of confusion with existing trademark filings, ensuring the new mark would not create consumer confusion with previously filed or registered marks. Compliance with trademark law also involves verifying that the mark is not deceptive, scandalous, or falsely suggests a connection with persons, institutions, or beliefs. Meeting these legal requirements helps ensure the trademark is entitled to protection under trademark law. If the examiner identifies any deficiencies, likelihood of confusion, or other issues with the application, they will issue an office action. You may receive one or more office actions, which is a letter from the Patent and Trademark Office requesting additional information, clarification, and/or amendments, and may contain refusals of the application due to a failure to comply with the requirements discussed above. An example scenario for issues raised in an office action for the hypothetical mark "Legal Maestro" for use on legal services could include the following:

These issues would need to be addressed adequately to overcome the office action and proceed with the trademark registration process. A response to an office action may be filed in order to address the issues raised by the trademark examiner. The response may include amendments to the goods or services, arguments against an examiner's assertion that there is a likelihood of confusion with prior filing, and/or responses to any formal requirements that the examiner has identified. If all issues are addressed, the examiner approves the application for publication.

Once the trademark examiner approves the application for publication, the mark is published in the United States Patent and Trademark Office's Trademark Official Gazette. Publication initiates a 30-day opposition period during which third parties can challenge the registration if they believe it will harm their trademark rights. If no opposition is filed, the application will advance to registration. Upon successful completion of these steps, the applicant receives a certificate of registration, granting exclusive rights to the applied-for trademark.

After trademark registration, the owner must maintain the mark by filing specific documents with the USPTO. Between the fifth and sixth years after registration, the owner must file a Declaration of Use (Section 8) to confirm the mark is in use in commerce and pay required fees. Additionally, every ten years, the owner must file a combined Declaration of Use and Application for Renewal (Sections 8 and 9). Failure to meet these maintenance requirements can result in the cancellation of the registration. Regular maintenance ensures the mark remains protected and continues to signify the source of goods or services. Trademark owners must keep records of your trademark use and maintenance to ensure you can prove ownership and use.

A trademark registrant has the exclusive right to use the registered mark in connection with the goods or services listed in the registration. This exclusivity allows the registrant to enforce their trademark rights by monitoring the marketplace for unauthorized use. If trademark infringement is detected, the registrant can file a lawsuit in federal court to seek remedies, including injunctions to stop the infringing use, monetary damages, and, in some cases, recovery of legal fees. Enforcing these rights helps protect the trademark's value and ensures the mark continues to signify the unique source of the goods or services.

After you register your trademark, you will have continuing responsibilities and rights as a trademark owner. As a trademark registrant, you must maintain and enforce the trademark. The trademark owner must ensure consistent use of the mark in commerce and monitor the quality of the goods or services associated with the trademark to prevent a loss of brand strength and enforceable trademark rights. To preserve your intellectual property rights, you must periodically file the required maintenance documents and fees. Additionally, the trademark owner must enforce their trademark against infringements in order to preserve the strength of the trademark. This includes opposing confusingly similar trademark filings, making cease and desist demands on infringing users, and, when necessary, filing trademark infringement lawsuits against obstinate infringers. Maintaining vigilance over the mark's use and quality helps uphold the trademark's integrity and value, ensuring that it continues to identify your business as the unique source of your goods and services in the marketplace.

Intellectual property (IP) refers to intangible assets that encompass the inventions, creative works, brand assets, literary and artistic works, and valuable knowledge and know-how of businesses, entrepreneurs, inventors, and creators. In most cases, intellectual property rights are creations of the mind that are captured in a tangible form, such as creative writing on paper, a new device built from tangible components, a brand logo presented on product packaging, or a song recorded on a tape or digital memory. However, in some cases intellectual property may never be captured in a tangible form. For example, a chemist may keep their secret method of temperature control and mixing processes to produce a certain chemical product a closely held secret and never capture it in written form. Unlike tangible assets (e.g., a car, a cow, gold, etc.), intellectual properties are legally protectable, intangible creations of the mind. Exclusive rights to these creations can be critical for maintaining a competitive advantage in the marketplace, as they allow IP owners to control the use and dissemination of their creations.

US federal law and state law provide legal protections to these valuable products of human intellect and skill. Different types of intellectual property rights serve to provide legal protection that incentivize creators and innovators to advance the sciences, technology, and the arts by allowing them to reap the benefits of their work. This article provides an exploration of intellectual property law in the US, covering patents, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets, and examining how intellectual property laws are designed to protect the interests of intellectual property owners.

A patent is a form of intellectual property protection that grants the patent owner the exclusive right to exclude other parties from making, using, selling, or importing an invention for a limited period, typically 20 years from the filing date of the patent application. Patents are designed to protect inventions and encourage innovation by providing inventors with a temporary monopoly in exchange for the public disclosure of their inventions.

Patent laws in the United States are established by the Patent Act, codified in Title 35 of the United States Code. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) administers the patent system, examining applications and granting patents. Federal courts exclusively handle the enforcement of patent rights if patent infringement occurs. A claim for patent infringement cannot be pursued in a state court. Patent owners can seek remedies such as injunctions and damages through civil litigation in federal court.

Trademarks are symbols, words, phrases, designs, colors, sounds, video clips, or combinations thereof that identifies the trademark owner as the source of its goods or services, allowing consumers to distinguish the goods or services from those of others. Trademarks serve to prevent consumer confusion and protect the goodwill associated with a brand. Trademark function differently from other forms of intellectual property. Whereas patents and copyrights reward creators for innovative or creative work, trademarks primarily serve to protect consumers by ensuring that brand names and symbols reliably identify a particular source of goods, thereby allowing the consumer to reliably purchase goods of a known quality from the source. To foster this consumer protection function, trademark law provides protections for trademark owners against unauthorized use of their marks. Trademark owners can establish rights through the mere use of a trademark in connection with goods and services, known as common law trademark rights. The trademark rights can be fortified and formalized through trademark registration.

Trademark law in the United States is primarily governed by the Lanham Act, which provides federal registration and protection of trademarks. The USPTO also administers the trademark system. As a federal agency within the Department of Commerce, the USPTO is responsible for implementing US intellectual property laws in the area of trademarks, examining trademark applications, and determining whether they meet the necessary legal requirements for registration. The trademark registration process involves a thorough review to ensure that the mark is distinctive, not confusingly similar to existing registered marks, and complies with all relevant statutory requirements.

Once a trademark application is submitted, the USPTO assigns it to a trademark examining attorney who reviews the application for compliance with the Lanham Act, the primary federal trademark statute. The examining attorney evaluates the mark’s eligibility for registration, considering factors such as distinctiveness, potential for consumer confusion, and any descriptive or generic qualities that may disqualify it from protection.

If the application meets all requirements, the USPTO will publish the mark in the Official Gazette, allowing the public an opportunity to oppose the registration. If no oppositions are filed, or if any oppositions are resolved in favor of the applicant, the USPTO will issue a registration certificate, granting the trademark owner exclusive rights to use the mark in connection with the specified goods or services.

In addition to federal protection, trademarks can be registered at the state level in California, Washington, Oregon, and states generally. Generally, the Secretary of State’s office administers the state trademark registration system.

Trademark infringement occurs when an unauthorized use of a trademark creates confusion about the source of goods or services, and remedies include injunctive relief and damages under both common law and statutory provisions. Enforcement of federal trademark rights can take place in either federal or state court, depending on the specifics of the case and the preferences of the trademark owner. When trademark infringement occurs, the trademark owner has the legal right to initiate civil litigation to protect their brand and prevent unauthorized use of their mark.

Federal courts are often preferred for trademark infringement cases. Federal jurisdiction is advantageous because the federal court is generally versed in federal trademark laws. State courts, on the other hand, can also hear trademark disputes, particularly those involving common law trademark rights, which arise from the actual use of a mark in commerce rather than federal registration. State law claims, such as unfair competition or dilution, may also be brought in conjunction with federal claims. The choice of state court may be influenced by factors such as the location of the parties, the scope of the alleged infringement, and strategic considerations.

Regardless of the venue, the enforcement process begins with the filing of a complaint outlining the trademark owner's claims. The court will then assess the evidence, including proof of ownership and the likelihood of consumer confusion caused by the infringing mark. Successful enforcement actions result in legal remedies, which may include injunctive relief (an order to stop infringing activities) and monetary damages.

Copyright is a form of protection granted to creators of "original works of authorship," such as literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works. Copyright law gives the copyright holder the exclusive right to reproduce, distribute, perform, display, and create derivative works based on the original work for a set period, generally the life of the author plus 70 years.

Copyright law is governed by the Copyright Act of 1976, codified in Title 17 of the United States Code. The U.S. Copyright Office, a part of the Library of Congress, administers copyright registration. The Copyright Act provides protection for "original works of authorship" fixed in a tangible medium of expression, covering a wide array of creative works, including literary, musical, dramatic, choreographic, pictorial, graphic, sculptural, audiovisual, sound recordings, and architectural works. Federal copyright law also includes provisions for the duration of protection. Generally, works created on or after January 1, 1978, are protected for the life of the author plus 70 years.

The fundamental purpose of copyright law is to encourage the creation and dissemination of creative works by granting authors certain exclusive rights for a limited period: rights to reproduce the work, create derivative works, distribute copies of the work, publicly perform the work, and publicly display the work. For sound recordings, the rights also include the ability to perform the work publicly by means of digital audio transmission. The law balances the rights of authors with the public interest by incorporating limitations and exceptions, such as the doctrine of fair use. The fair use doctrine allows the use of copyright works without permission for certain purposes that benefit the public, including news reporting, research, teaching, scholarship, comment and criticism. Other exceptions include certain uses by libraries and archives, educational performances and displays, and specific reproductions for individuals with disabilities. By providing robust protection and a framework for the fair use of creative works, federal copyright law aims to stimulate creativity and the dissemination of knowledge, ultimately benefiting both creators and the public.

Copyright protection arises automatically upon the creation of a work that meets the originality and fixation requirements. However, registration with the U.S. Copyright Office, although not mandatory, offers significant advantages. Registration establishes a public record of the copyright claim, is necessary to bring a lawsuit for infringement, and allows for the possibility of statutory damages and attorneys' fees.

Enforcement of copyright law is primarily achieved through civil litigation. Copyright litigation can only be pursued in federal court. The plaintiff must establish that they own a valid copyright, which can be demonstrated through registration with the U.S. Copyright Office. Registration is a prerequisite for filing an infringement lawsuit for works created after January 1, 1978.

The elements of a copyright infringement claim include proving ownership of a valid copyright and demonstrating that the defendant copied protected elements of the work. This involves showing access to the copyrighted work and substantial similarity between the original work and the alleged infringing work.

Once copyright infringement is established, various remedies are available to the copyright owner. These include injunctive relief to prevent further infringement, actual damages to compensate for financial losses, and statutory damages, which can range from $750 to $30,000 per work infringed, and up to $150,000 per work for willful infringement. Additionally, courts may award attorneys' fees and court costs to the prevailing party.

In cases of willful infringement, criminal penalties may also be imposed, including fines and imprisonment. These remedies aim to deter infringement and compensate the copyright owner, ensuring the protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights.

A trade secret is any confidential business information that provides a competitive edge, such as formulas, practices, processes, designs, instruments, patterns, or compilations of information. Unlike other forms of IP, trade secrets are protected as long as they remain confidential and are subject to reasonable efforts to maintain their secrecy.

The Federal Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA), enacted in 2016, represents a significant advancement in the protection of trade secrets in the United States. Before the DTSA, trade secrets were governed exclusively by state laws, leading to inconsistencies across jurisdictions. The DTSA provides a federal cause of action, allowing trade secret owners to sue in federal court for misappropriation.

The DTSA defines a trade secret broadly to include all forms and types of financial, business, scientific, technical, economic, or engineering information, provided it is subject to reasonable measures to keep it secret and derives independent economic value from not being generally known or readily ascertainable.

Under the DTSA, plaintiffs can seek remedies such as injunctions to prevent the use or disclosure of misappropriated trade secrets, monetary damages for actual losses and unjust enrichment, and in cases of willful and malicious misappropriation, exemplary damages up to twice the amount of actual damages. The DTSA also provides for the recovery of attorneys' fees.

Additionally, the DTSA includes provisions for civil seizure, allowing courts to order the seizure of property necessary to prevent the dissemination of trade secrets in extraordinary circumstances. This federal framework enhances the protection of trade secrets, promoting innovation and safeguarding competitive advantage in the marketplace.

The Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA) provides a standardized legal framework for the protection of trade secrets, adopted by the majority of U.S. states to bring consistency and clarity to trade secret law. Before the UTSA, state laws regarding trade secrets varied significantly, creating challenges for businesses operating across multiple states.

Under the UTSA, a trade secret is information having independent economic value as a secret and is subject to reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy. This includes a wide range of confidential business information, such as formulas, patterns, compilations, programs, devices, methods, techniques, or processes.

The Act outlines the elements of trade secret misappropriation, which occurs when a trade secret is acquired through improper means or disclosed or used without consent. Remedies under the UTSA include injunctive relief to prevent further misappropriation, monetary damages for actual losses and unjust enrichment, and in cases of willful and malicious misappropriation, exemplary damages up to twice the amount of actual damages. The UTSA also provides for the recovery of attorneys' fees in certain circumstances.

California, for example, has adopted the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA), codified in the California Civil Code. The California UTSA provides robust protections for trade secrets, including the ability to seek injunctive relief and damages for misappropriation.

While federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over patent and copyright cases, both federal and state courts can hear trademark and trade secret cases, depending on the circumstances. California state courts play a crucial role in the enforcement of state-level IP rights, such as trade secrets and the right of publicity.

Intellectual property lawyers play a vital role in advising clients on the protection, enforcement, and commercialization of their IP rights. They assist with the registration of patents, trademarks, and copyrights, represent clients in IP litigation, and provide counsel on matters related to IP strategy and technology transfer. Intellectual property lawyers help IP owners navigate the complex landscape of IP laws to maximize the value of their intangible assets.

The protection of intellectual property extends beyond national borders. International agreements establish minimum standards for IP protection. The treaties include the Patent Cooperation Treaty, governing an international patent system and the Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks that established an international trademark registration system, both administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization. These agreements ensure that IP rights are recognized and enforced globally, facilitating international trade and investment.

Having read the foregoing, you should now be able to provide a fairly informed answer to the questions "What is intellectual property?" Intellectual property laws are essential to the business environment, as they stimulate innovation and reward technological progress, protect creative works, and drive economic growth. By understanding the different types of intellectual property protection, including patents, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets, individuals and organizations can consider and strategize about what their intellectual property assets and which of them they need to safeguard through registrations, patenting, and/or confidentiality protections.

As intellectual property law continues to evolve, staying informed about legal developments at both the federal and state levels remains essential for effective IP management and enforcement. Intellectual property lawyers can provide valuable guidance to intellectual property owners, shepherding them through the registration and patenting processes at the US Patent and Trademark Office and the US Copyright Office. The protection of intellectual property is vital for entrepreneurs and businesses who are geared to toward innovation.

If you or your business needs assistance with intellectual property matters, contact our firm for a free consultation. We are experienced and skilled in all areas of intellectual property law.

The novelty requirement is a foundational aspect of US patent law. An invention must be something new in order to be considered patentable. Patents are only granted for inventions that are truly new. Anticipation is not the only requirement for patentability. Novelty is one of several statutory requirements, including patent-eligible subject matter, novelty, obviousness, written description, enablement, and definiteness. We provide separate articles for each of these requirements. This article explains the novelty requirement, including key concepts like anticipation and inherency.

The novelty requirement is primarily codified in 35 U.S.C. § 102. This section sets forth the conditions under which an invention is considered novel. The statute has undergone significant changes, most notably with the passage of the America Invents Act (AIA) in 2011, which transitioned the U.S. from a "first-to-invent" system to a "first-to-file" system. Under the pre-AIA law, the focus was on whether the invention was known or used by others in the U.S. before the applicant's date of invention or whether it was patented or described in a printed publication anywhere in the world before the invention date. Post-AIA, the critical date shifted to the filing date of the application, and the relevant prior art includes disclosures anywhere in the world before the effective filing date.

35 U.S.C. § 102 outlines the conditions for patentability with respect to novelty. The claimed invention in a patent application must be new relative to the relevant prior art. Thus, in order to understand the novelty requirement, you must understand what qualifies as prior art with respect to a particular patent application.

A claimed invention is not novel if it was patented, disclosed in a printed publication, publicly used, offered for sale, or otherwise available to the public before the priority date of the patent application. Additionally, if the claimed invention was described in a patent or in a patent application published or deemed published under 35 U.S.C. § 122(b), and the patent or application has different inventorship and was effectively filed before the effective filing date of the claimed invention, it is considered prior art. For determining whether a patent or application is prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(2), the patent or patent application reference is considered to have been effectively filed as of the actual filing date, or the earlier filing date of a prior filed application if it claims priority to the prior-filed application.

The statute also provides exceptions under 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). Disclosures made one year or less before the effective filing date of the claimed invention are not considered prior art if the disclosure was made by an inventor, joint inventor, or someone who obtained the subject matter disclosed directly or indirectly from one of the inventors. Moreover, prior art does not include subject matter publicly disclosed by the inventor or a joint inventor before the effective filing date of the patent application.

Another critical aspect is the consideration of joint research agreements under 35 U.S.C. § 102(c). Subject matter disclosed and the claimed invention are deemed to have been owned by the same person or entity if they were developed under a joint research agreement in effect on or before the effective filing date of the patent application. The patent application must disclose the names of the parties to the joint research agreement.

An applicant’s identification of another's work as "prior art" in the specification or during prosecution is an admission usable for anticipation determinations, even if it would not otherwise qualify under 35 U.S.C. § 102. However, the inventor's own work is not prior art unless statutorily qualified. Examiners must verify if the admitted prior art is the inventor’s or another’s work, treating it as another’s in the absence of evidence.

A single prior art reference must disclose all the elements of the claimed invention in order to anticipate the patent claim. This means that the prior art must explicitly or inherently disclose every aspect of the claimed invention. The novelty requirement prevents the patenting of inventions that are already known and encourages innovation by ensuring that only new and unique inventions are granted patent protection. The prior art reference must be enabling to one or ordinary skill in the art in order to be a proper prior art reference. This means that the reference must provide sufficient information for a person of ordinary skill in the art to practice the claimed invention without undue experimentation. The prior art reference must include a level of detail that allows a skilled person to understand and practice the claimed invention. This includes descriptions of the invention's components, methods, and any necessary conditions or parameters. This concept applies both to patent applications and prior art references used to challenge the novelty of a patent claim.

Claim: A pharmaceutical composition comprising:

Prior Art Reference: A scientific journal article published two years before the effective filing date of the patent application describes a pharmaceutical composition that includes Compound X in a therapeutically effective amount and citric acid in a concentration of 0.5 micromolar in a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

Analysis: In this case, the prior art discloses all the elements of the claimed invention. The composition described in the journal article includes Compound X, citric acid in the claimed range, and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier. Therefore, the reference anticipated the claimed invention because all of the elements were disclosed.

The same claim would not be anticipated by a scientific journal article published two years before the effective filing date of the patent application describes a pharmaceutical composition that includes Compound X in a therapeutically effective amount and citric acid at a concentration of 2.0 micromolar in a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier. Additionally, a different prior art reference from a different journal describes Compound X and citric acid in the claimed range, but does not combine it with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

Analysis: In this scenario, no single prior art reference discloses all the elements of the claimed invention. The first journal article describes a composition with Compound X and a carrier, but the citric acid is not in the claimed concentration range. The second reference disclosed compound X and citric acid in the claimed range, but does not disclose the pharmaceutically acceptable carrier claim limitation. Because there is no single reference that discloses all of the claimed elements, the claim is not anticipated.

There are some further nuances to the application of an anticipation rejection, which are discussed below.

Inherent disclosures of a prior art reference can be used to reject claims as anticipated under 35 U.S.C. 102. Inherency refers to implicit features within prior art that are not explicitly stated in the written description, but are necessarily present. A discovery of a new property of a prior art composition does not make it patentable. For example, the identification of a previously unrecognized DNA sequence does not render the sequence novel if it was inherently present in prior art. The inherent feature does not need to be recognized at the time of the prior art's publication. Even if the characteristic was unknown, it can still anticipate the claim if it is a necessary feature of the prior art. Anticipation rejections are appropriate when a prior art product appears identical to the claimed subject matter, except that the prior art is silent about an inherent characteristic. The US patent office must identify and provide evidence that the missing limitation is inherent in the prior art technology. The patent examiner must demonstrate that the asserted inherent characteristic is actually inherent in the subject matter disclosed by the prior art reference. This principle applies to product, apparatus, and process claims described in terms of function, property, or characteristic. Hence, inherent features in prior art references play a critical role in patent examinations and litigation.

Anticipation of ranges in patent claims is determined by whether a prior art reference disclosing a specific example falls within the claimed range. In the example of above, the prior art disclosed a pharmaceutical composition that includes Compound X in a therapeutically effective amount and citric acid in a concentration of 0.5 micromolar in a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier, where the claim recited citric acid in a range of 0.1 micromolar to 1.0 micromolar. Thus, the prior art reference anticipates the claim because 0.5 micromolar falls in the claimed range. A prior art reference disclosing a value or range close to but not overlapping or touching the claimed range does not anticipate the claim.

Anticipation in genus-species situations involves whether a prior art reference disclosing a species can anticipate a claim to a broader genus. If a prior art reference discloses a specific species within a claimed genus, it anticipates the genus claim. For example, if a reference names a specific chemical species within a Markush claim of a genus of compounds, the species can anticipate the entire genus. A Markush claim is a type of patent claim used to define a genus by specifying a list of alternative species or elements within a single claim, as follows: "A composition comprising a member selected from the group consisting of A, B, C, and D." If a reference disclosed a composition comprising A, it would support an anticipation rejection.

However, a genus does not always anticipate a claim to a species within that genus unless the species is clearly named in the reference. For example, if a reference lists multiple compounds, the mere inclusion of a claimed species among them anticipates the species claim.

A generic disclosure will anticipate a claimed species when the species can be "at once envisaged" from the disclosure. This means that the prior art must provide sufficient detail that a person skilled in the art can immediately recognize the specific species within the broader genus. For example, in Kennametal, Inc. v. Ingersoll Cutting Tool Co., a prior art reference was found to anticipate a claim because it provided sufficient evidence that a person skilled in the art would immediately envisage the specific combination of elements. In contrast, if a generic formula encompasses an infinite number of compounds, a specific compound within that formula is not anticipated unless the reference provides a more limited and detailed disclosure. This was highlighted in In re Meyer, where a specific compound was not anticipated because the prior art limited the generic composition disclosure.

In summary, anticipation in genus-species situations depends on the specificity and detail provided in the prior art reference. A specific species can anticipate a genus, and a generic disclosure can anticipate a species if it allows the species to be readily envisaged.

While normally a single reference is used for rejections under 35 U.S.C. § 102, multiple references can be employed under specific circumstances: to prove the primary reference contains an "enabled disclosure," to explain the meaning of a term in the primary reference, or to show an inherent characteristic not explicitly disclosed.

These scenarios highlight the flexibility in applying multiple references to ensure a comprehensive assessment of the primary reference's disclosure, enabling a proper anticipation rejection under 35 U.S.C. 102.

During patent examination, the examiner searches for prior art, such as printed publications or patents, that are published and that were filed prior to the priority date of the examined patent application. This involves comparing the effective filing date of the patent application and the date of the reference. The examiner must also ascertain the issue or publication date of the reference to make a proper comparison. If the reference predates the effective filing date of the claimed invention, it may be used to in an anticipation rejection. The examiner may also look to evidence of public use, sale, or knowledge of the invention by others. This includes admissions by the applicant or examiner’s knowledge of the invention’s public disclosure.

Examiners can request additional information from applicants to resolve issues related to public use or sale, ensuring that the information sought is reasonably necessary for the patentability decision. Failure to respond to these requests within the specified timeframe can result in the application being considered abandoned.

Applicants can overcome a 35 U.S.C. § 102 rejection by arguing that the reference fails to disclose each and every element in the claim language, the reference is not enabled, and/or by amending the claims.

Understanding the nuances of prior art disclosure, including the timing of disclosures is crucial for inventors and patent practitioners. The statutory provisions under 35 U.S.C. § 102 provide a comprehensive framework to assess the novelty of a claimed invention, ensuring that patent claims are genuinely new and not anticipated by prior art references. The novelty requirement protects the public from the unjustified patenting of existing knowledge, thereby encouraging new innovation.

Generic terms cannot function as a trademark, and thus the phrase "generic trademark" is an oxymoron. Trademark law can be a bit confusing on the subject of generic terms. This article defines and clarifies what a generic term is in order to enable trademark owners to avoid the genericness problem in their pursuit of trademark protection.

Trademark terms are categorized into four levels of descriptiveness with regard to their potential for protection: generic marks, descriptive trademarks, suggestive marks, and fanciful or arbitrary marks. Generic terms are common names for products or services and cannot be protected as they do not identify the product's source. At the other extreme, arbitrary or fanciful marks use words or phrases with no direct connection to the product, identifying the source with inherent distinctiveness, and thus automatically qualifying for trademark protection. An example of an arbitrary or fanciful mark is Nintendo for video games. Descriptive terms directly describe a characteristic or quality of the product and can only be protected if they acquire a secondary meaning. An example of a descriptive mark is International Business Machines (IBM) for computers. Suggestive terms imply qualities or characteristics, requiring imagination to connect to the product, and are inherently protectable. An example is Tesla Motors, as Tesla suggests the electric motors of the vehicles.

There is a spectrum of protectability for trademarks, from generic terms to arbitrary or fanciful marks. Generic terms like "apple" for the fruit lack protection because they denote a class of products. In contrast, arbitrary terms like "Apple" for computers are highly protectable due to their distinctiveness and lack of inherent connection to the product.

A generic term is a term that serves as a name of the actual product or service that the seller is offering. It should be understood that “generic” in the context of trademark law has a specific meaning and does not imply that common terms cannot be registered as trademarks. For example, simple, common words like Apple and Guess are routinely registered as trademarks. The critical factor is whether the trademark is descriptive of goods or services offered under the mark to the point that it is a name for the goods or services. “Apple” does not identify consumer electronics, and Guess does not identify clothing. Generic terms are not capable of distinguishing the source of one product from a competitor because they refer to an entire class or genus of products. An example of a generic mark is ‘cycle’ is a generic term for a two-wheeled vehicle, so generally speaking, a bicycle company would not be able to register, e.g., CYCLE CO as a trademark for use on its bicycles. A company seeking to protect its brand should pick a company name and brands that avoid the genericness problem.

A term can be a generic name for one thing but may still be considered a valid trademark for some other product. Apple does not sell the fruit; the company sells computers. Similarly, Shell in no way provides goods or services relating to the covering of an egg, but rather sells gasoline.

Trademarks act to identify and distinguish the goods and services provided by one seller under a particular brand from those of the others. Generic terms, designations that refer to the same product or service they supposedly identify the source of, do not provide this function. Since the name of a product or service offered cannot identify its source, it cannot function as a trademark and cannot be registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). If this were not the case, one seller could trademark their product or service and preclude the use of the term by competitors offering the same product or service. This would be akin to granting a monopoly on identifying a particular product.

The genericness test turns on the (relevant) public’s perception of the mark in question. The general test asks: what does the relevant consumer understand the word to refer to—the generic name of a product or a mark indicating one source of that product? Two considerations flow from this general question.

This test may seem to render a term generic if buyers often call or order a product using that specific term. For instance, people commonly refer to photocopy machines as ‘Xerox Machines,’ and photocopying as ‘Xeroxing.’ However, it is the use and understanding of the term in the context of purchasing decisions that determines the primary significance of the designation. Unfortunately for the Xerox Corporation it was in jeopardy of losing its trademark registration. It had to fight off the generic usage of "xerox" through an expensive advertising effort to shift the public usage to "photocopying" documents, in order to protect its XEROX registration and associated intellectual property rights.

A simple and helpful way of understanding the basic question of whether a term is generic is to ask the following question: In the minds of the consumers, does the term provide an answer to what the product is (generic), or does it answer where it comes from (source identifier)?

Genericide is a potential pitfall for trademark owners. Genericide describes a situation in which one seller obtains trademark rights for a term which is in turn appropriated by the relevant public to refer to the name of a product. The term may therefore become generic, and the associated exclusive right to use the trademark can be lost.

There are two common causes of genericide. The first is when a new product is developed, and the term intended to be used and registered as a trademark is taken by the public and used in a generic way. Because it is a new product, the buyers have no other word to use. The second is the failure to police the usage by competitors, which can thereby influence its usage among consumers. By observing the term is used among many sellers, the consumers may begin to see the term as generic. If genericide occurs, all trademark protection is lost and the competitors can use the mark without risk of trademark infringement. There are famous examples of genericide resulting in a registered trademark becoming generic, including:

These examples illustrate how certain trademarks have lost their distinctiveness and become generic, often due to widespread consumer use that associates the term with the product category rather than a specific brand.

Once the public begins to identify a trademarked term as the name for the trademark owner's product and perhaps similar products, it is very difficult for the trademark owner to reverse the trend. It is therefore crucial to take precautions because once a trademark becomes a generic term, it provides no legal protection to the business that uses it. Two strategies in particular can help companies maintain their trademark protection and defend against genericide:

There are different kinds of patent protection under US patent law. Typically, when one thinks about "patentable subject matter", they are thinking about an invention. Patents that cover an invention (e.g., a new device, method, composition of matter, etc.) are utility patents. There are several patentability requirements for utility patents. An invention is evaluated by the US Patent and Trademark Office under the following four statutory categories: patent eligible subject matter (the right kind of thing), novelty (it must not have been done/made before), nonobviousness (minimal changes to existing technology are not enough), and clarity and enablement (the invention must be functional and properly described). The invention must meet each of these requirements to qualify for a patent. This article provides an explanation of what qualifies as patent eligible subject matter - the kind of thing that can be patented.

Subject matter eligibility under U.S. patent law requires an invention to meet specific criteria set forth in 35 U.S.C. § 101. This statute outlines four categories of patentable subject matter: processes (methods - series of steps or acts), machines, manufactures, compositions of matter, or a new and useful improvement thereof.

An eligible method invention involves a series of steps or actions to achieve a specific result. For example, consider a novel method for manufacturing a semiconductor device. The claimed method might involve a series of steps such as depositing layers of materials, patterning them using photolithography, and etching to create microstructures. This claimed method would fall under the process category and could be eligible for a process patent if it meets other criteria, such as novelty and non-obviousness. Here are some further examples of new and useful process subject matter:

Machines are tangible devices or apparatuses designed to perform specific functions. For instance, an innovative robotic arm used in manufacturing that includes new and useful improvements over existing technology can be patented. This robotic arm might integrate advanced sensors, AI algorithms for precision, and energy-efficient motors, making it a valuable invention in the field of automation.

A more familiar example is the computer. Patents on computer hardware innovations, such as faster processors, more efficient cooling systems, or improved data storage solutions, fall under the machine category. These innovations must be concrete and specific, avoiding abstraction to meet the criteria for patent eligibility. Here are some further examples of appropriate subject matter under the machine category:

The manufacture category includes items that are made or produced, often through industrial processes. For example, a new type of biodegradable plastic, created by synthesizing polymers from renewable resources, could be patented. This new material, which decomposes more quickly than conventional plastics, addresses environmental concerns and represents a significant advancement in materials science. Here are some further examples of appropriate subject matter under the manufacture category:

This category includes chemical compositions and compounds. Pharmaceuticals are a prime example. A new drug that effectively treats a disease with fewer side effects represents a patentable composition of matter. The patent application would cover the specific chemical structure of the drug, which is proper subject matter under section 101.

Improvements on existing technologies form a significant category of patentable subject matter, often leading to incremental but valuable advancements in various fields. According to the Patent Act, any new and useful improvement of a process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter can be patented. The essence of this category lies in enhancing the functionality, efficiency, or utility of existing inventions, making them more effective or adaptable. Here are some examples:

Patentable improvements drive technological progress by building on existing inventions. These new and useful enhancements not only offer practical benefits but also qualify for patent protection, encouraging continuous innovation and development across various industries.

While an invention must fall into a statutory category to be patent eligible, fitting into one of these categories alone does not guarantee patent subject matter eligibility. The Supreme Court has established an exclusionary principle that holds that a claimed invention that is directed to an abstract ideas, laws of nature, or a natural phenomena cannot be patented. These judicial exceptions are based on the concern that granting patents for "basic tools of scientific and technological work" would impede innovation, rather than promote it. Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63 (1972). This principle was reinforced by the Supreme Court in cases such as Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l and Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., which established a two-part test for determining patent eligibility.

If the claim includes a judicial exception, it will likely be rejected by a patent examiner. However, if there is a novel, innovative concept within the claim, the inventive aspect may be sufficient to confer patent eligibility to the patent claim. The following is an example of a claimed invention that includes an natural phenomenon, but also includes an inventive concept that may overcome a judicial exception rejection under the natural phenomenon exclusion.

A claim for a method for diagnosing a disease may include obtaining a blood sample from a subject; determining the presence or absence of a biomarker in the blood sample by using a specific reagent that selectively binds to the biomarker; comparing the level of the biomarker in the blood sample to a predetermined threshold level; diagnosing the subject with the disease if the level of the biomarker is above the predetermined threshold level and the reagent is a novel engineered protein that improves the specificity and sensitivity of the biomarker detection. The claim involves a method of diagnosing a disease, which falls under the category of "laws of nature" or "natural phenomenon." This is because the correlation between the biomarker level and the disease is a natural phenomenon.

Despite involving a judicial exception, the claim includes a novel engineered protein. The inclusion of a novel engineered protein as a specific reagent that selectively binds to the biomarker is a concrete and inventive step. This protein improves the specificity and sensitivity of the biomarker detection compared to existing methods, thus adding man-made chemical that is significantly more than just the natural correlation. The novel engineered protein provides a technological improvement created by the scientific and technological work of man, which is a significant step beyond the abstract idea or natural law. The method claim satisfies as a whole demonstrates a practical application of the natural correlation in a way that provides improved diagnosis, a tangible and useful result.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) employs a meticulous approach when analyzing patentable subject matter, ensuring that each application meets statutory requirements before granting patent rights. A key aspect of this examination is claim interpretation, specifically under the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) standard. This method plays a crucial role in determining whether an invention encompasses subject matter eligible for patent protection.

When evaluating a patent application, the USPTO applies the broadest reasonable interpretation to the claims. This means that the claims are interpreted in their broadest form consistent with the specification as understood by someone skilled in the art. The purpose of this approach is to establish a clear boundary of what the patent covers, thus ensuring that the claims are not interpreted in an unduly broad or vague manner. This claim construction is essential in identifying claims that meet the criteria for patentability.

The BRI standard affects the evaluation process by ensuring that the claim interpretation affects the breadth and scope of the claimed invention. The examiner determines if the interpreted claim encompasses subject matter that falls into one of the statutory categories. The examiner also assesses whether the claim is directed to a patent ineligible concept such as an abstract idea, law of nature, or natural phenomenon.

To determine patentability, the examiner conducts the following detailed analysis of the claims:

When a claim is found to be patent ineligible, the examiner provides a detailed explanation, identifying the specific reasons for ineligibility. This includes discussing how the claim falls within a judicial exception and lacks additional elements that confer patentability. Applicants may then respond by amending claims or providing arguments to demonstrate eligibility. The USPTO’s approach to claim interpretation under the broadest reasonable interpretation standard is a cornerstone in the patent examination process. The goal of the BRI standard is clarity and precision in determining patentability, thereby maintaining a balanced system that fosters innovation while preventing overly broad or ambiguous claims. By carefully evaluating eligibility based on this standard, the USPTO ensures that only inventions meeting stringent criteria are awarded patent protection, thus upholding the integrity of the patent system.