An invention must be non-obvious when compared to related prior art. Specifically, under 35 U.S.C. § 103, an invention cannot be patented if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the invention as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains.

The evaluation of obviousness involves a multi-step analysis, typically beginning with the identification of the scope and content of prior art related to the claimed invention. The next steps involve ascertaining the differences between the prior art and the invention at issue and assessing the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art.

The seminal case of Graham v. John Deere Co. of Kansas City established the framework for assessing obviousness, which includes examining these objective indicators. Later cases, such as KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc., have evolved the standards, emphasizing a flexible, expansive approach to determining obviousness, which includes an understanding that obviousness can be based on common sense and the ordinary creativity of those skilled in the art. This move away from a rigid, formulaic approach allows for more nuanced considerations of what constitutes an obvious improvement in a field, ensuring that patents only cover truly innovative advancements.

A proper obviousness rejection under must meet several key requirements. First, there must be a clear identification of the relevant prior art that would have been known to a person having ordinary skill in the art (POSITA) at the time the invention was made. The rejection should explicitly state which specific prior art references are being combined and how they relate to each element of the claimed invention. Additionally, the rejection must include a rationale for combining these references, supported by a reasoned explanation that includes factual findings. This rationale should demonstrate that the combination of prior art references would have been obvious to a POSITA, not merely speculative or general. The rejection also needs to address any teaching away by the prior art, which could argue against the combination. Finally, any assertions of obviousness must consider the claimed invention as a whole and not just individual elements in isolation.

Prior art refers to all information that has been made available to the public in any form before the effective filing date of a patent application. Under the US Patent Act, the patentability of an invention depends on how distinctive it is from the closest related prior art. Examples of prior art include previously issued utility patents, design patents, published patent applications, and other public disclosures such as articles, books, or products on the market, which predate the filing of the patent application under examination. The effective filing date of a patent application is the reference point to determine whether particular information qualifies as prior art.

Patent examiners perform a prior art search to find prior art related to the invention claimed in the patent application. When a patent examiner finds prior art that predates the effective filing date and discloses similar innovations, the examiner may cite the prior art found to reject the claimed invention as anticipated or obvious. This process ensures that patents are granted only for genuinely new and inventive contributions to the field.

A proper obviousness rejection must based on prior art that is "analogous" to the claimed invention. See M.P.E.P. § 2141.01(a). A reference qualifies as “analogous” if it meets one of two separate tests. There is the "field of endeavor" test, which requires that the prior art reference is from the same field of endeavor. The other test requires that the prior art reference is "reasonably pertinent" to a particular problem addressed by the claimed invention. In re Klein, 647 F.3d 1343, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (quoting In re Bigio, 381 F.3d 1320, 1324 (Fed. Cir. 2004)). These tests are exclusive to one another. If the prior art meets the field of endeavor test, it need not address the problem addressed in the patent application. If the prior art meets the reasonably pertinent test, it need not be in the same field of endeavor.

In an exemplary case, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board issued a decision in Ex parte Taskinen reversing obviousness rejections because the examiner did not properly establish that a cited secondary prior art reference was analogous to the claimed invention. The patent application disclosed adjustable massage apparatuses. The examiner rejected the claims as being obvious in view of Taskinen (US 2008/0200778), Khen (WO 2008/063478), and Lockwood (US 2003/0014022). Lockwood discloses wound treatment apparatuses.

The examiner asserted that Lockwood is the in the same field of endeavor as the invention, but failed to explain how Lockwood's disclosure was analogous to massage apparatuses. The examiner offered no assertion or explanation as to whether Lockwood was “reasonably pertinent” to the invention described in the patent application. The applicant challenged the examiner's assertion that Lockwood was in the same field of endeavor, arguing that a POSITA would not look to Lockwood because the structure and purpose the devices disclosed by Lockwood are unrelated to massage devices. Applicant argued that while Lockwood describes a low pressure suction device, the structure and purpose of the Lockwood device are different than a massage apparatus. Ergo, a POSITA would look to Lockwood in conceiving the device disclosed by the primary reference, Taskinen. Applicant further argued that a POSITA would not combine features of Lockwood with Taskinen because they were not practicably combinable with the device of Taskinen.

The Board found that Lockwood was not in the same “field of endeavor” as the claimed invention, because massage devices are not remotely vacuum treatment devices. The Board explained that the field of endeavor test requires the examiner to determine the appropriate field of endeavor by reference to explanations of the invention’s subject matter in the patent application, including the embodiments, function, and structure of the claimed invention. In re Bigio, 381 F.3d at 1325. The test is not satisfied by a subjective determination by the patent examiner. Id. at 1326. The patent office must have a basis in the application and its claimed invention for defining the scope of the field of endeavor. Id.

The Board found that the patent examiner's opinion that Lockwood was in the same field of endeavor did not find a basis objective evidence, and amounted to an unsupported legal conclusion. The field of endeavor identified by the examiner (vacuum treatment devices for a user) was too generic. The PTAB found that Appellant’s field of endeavor was actually massage devices, as demonstrated by the technical field, the discussion of the prior art, the detailed description of the invention, the figures, and the patent claims provided in the patent application. This case illustrates that the patent applicant must carefully review the prior art relied upon by the patent office and challenge obviousness rejections based on non-analogous art.

A prior art reference meets the "analogous art requirement" and can be relied upon in an obviousness rejection under 35 U.S.C. § 103 if it is reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved. The reasonably pertinent test is independent of whether a prior art reference is from the same field of endeavor.

The test for whether a prior art reference is "reasonably pertinent" does not require the prior art to be in the exact field of the claimed invention; rather, a reference is reasonably pertinent if the prior art at least one of the issues addressed by the claimed invention and has the same purpose with respect to that issue.

In the case of Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc., the Federal Circuit addressed the applicability of the "reasonably pertinent" test for determining analogous art in patent law. This case highlighted critical issues regarding the classification of prior art as analogous in the context of an inter partes review (IPR) proceeding before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.

Sanofi’s ’614 patent, which pertained to a metered drug-dosing device, was challenged by Mylan who argued that the patent was obvious in light of three prior art references: Venezia, Burren, and primarily, de Gennes. The latter, though related to automobile technology—a field distinct from drug delivery—was claimed by Mylan to be analogous because it addressed similar mechanical issues.

The crux of the dispute revolved around whether de Gennes was "reasonably pertinent" to the specific problem addressed by the ’614 patent. The Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB) initially found de Gennes to be analogous art, reasoning that it dealt with relevant mechanical issues despite its primary application in a different field. However, this conclusion was based on an indirect comparison where de Gennes was aligned with Burren rather than directly with the ’614 patent.

On appeal, Sanofi argued that PTAB improperly expanded the scope of analogous art by shifting the burden from Mylan to Sanofi, requiring the patentee to prove non-obviousness. The Federal Circuit sided with Sanofi, noting that patent challengers must clearly establish the pertinence of prior art directly to the challenged patent. The Court emphasized that the determination of whether a reference is "reasonably pertinent" relies on its direct relevance to the problem addressed by the patent in question, not merely its presence in related discussions or its utility in solving similar issues in a different context.

The Federal Circuit's decision underscores the necessity for patent challengers to meticulously demonstrate the relevance of prior art to the specific patent challenges, particularly through the lens of the "reasonably pertinent" standard. It serves as a reminder that the burden of proof in establishing obviousness lies with the challenger, who must convincingly show that the prior art directly pertains to the patented invention.

The foregoing cases illustrate that both patentees and challengers to thoroughly evaluate and argue the analogous nature of prior art from the earliest stages of patent disputes. Legal frameworks require that the art must either be within the same field of endeavor or reasonably pertinent to the particular problem addressed by the invention. Court decisions like Sanofi-Aventis have underscored the necessity of that the prior art must be sufficiently related to to the invention for it to be a proper basis for rejecting a patent claim as non obvious. The patent office must meet the legal requirements and its own examination guidelines in determining whether an invention is obvious.

Introducing new product ideas and services is the life blood of many businesses. There are numerous steps along the path to a developing a new product vision. For instance, a product idea must be evaluated for its technical feasibility, manufacturing costs, and potential profit margins. Additionally, as part of the product design process, a company must conduct thorough market research to identify related products and potential competitors for the proposed new product. These steps are absolutely necessary at the product development stage to enable an effective product development. However, while necessary, these steps are not sufficient to effectively launch a final product or service.

Beyond developing new product opportunities that address customer needs, a business must also consider whether a new product or service presents a potential infringement lawsuit due to a third party patent covering the new product or service. A comprehensive patent search and review process prior to a product launch can reveal whether a proposed innovation infringes on such patents. In some circumstances, there may be competitive products that are covered by one or more patents. In other cases, there may be third party patents that are not connected to any existing product in the marketplace. For example, there may be patents that cover an unlaunched product currently under development or the patent owner may have no plans to make the patented invention.

In order to identify such patents, a thorough freedom to operate search of issued patents and pending patent applications must be conducted to allow evaluation of infringement risks. This step should be taken by a company to avoid infringement liability resulting from a new product launch. In the event that the new product idea poses an infringement risk, the freedom to operate search and analysis may provide a roadmap for a revised product strategy to either design around existing patents or engage in licensing negotiations with the patent owner. This proactive approach is necessary to avoid legal pitfalls that can doom the new innovation and secure a smoother market entry.

Businesses that are engaged in the product development process must consider the risk of infringing a patented invention. If any such patent rights are found, the client may wish to do an in-depth infringement analysis to determine whether there is a real risk of infringement. Infringement analyses and non-infringement opinions of closely related patents identified in a freedom to operate search or otherwise are due diligence exercises that inform a client about either present or potential patent infringement risks. A non-infringement opinion can provide cover against claims of willful patent infringement. There are several situations in which an infringement analysis and non-infringement opinion are prudent. Where a freedom to operate search has been performed and related, enforceable patents have been identified. The need for infringement analysis and a non-infringement opinion also commonly arises where a client receives a cease and desist letter asserting that the client is infringing one or more patents. The client, of course, will wish to investigate the merits of the asserted patent infringement claim(s). There are other situations where a non-infringement opinion is a prudent exercise. Another situation in which the infringement analysis may be needed is where a client is seeking to develop a new product or new service, but is aware that a competitor offers a related product or service and has one or more patents related to such product or service. The client would naturally want to know its infringement exposure risk before launching a product or service that directly competes with its rival’s patented offerings. Such due diligence should be stand a standard business analysis step for companies engaging in product development.

The benefits of an infringement analysis include (1) the client becomes well-informed of the infringement risk posed by patents on related goods or services issued to third patent owners, and (2) design around strategies may be formulated to allow the client to move forward with a competing product or service without risking infringement. If it is found that the client’s new product or service offerings do not or likely do not infringe the analyzed patent(s), then a non-infringement opinion can be written that provides a good faith basis for the client to move forward with the product or service with confidence that they likely do not infringe the patents discussed in the non-infringement opinion.

Additionally, the non-infringement opinion can be used as a shield against assertions of willful infringement. Willful infringement requires a finding of recklessness on the part of the infringer, and can result in enhanced monetary damages awards of up to three times the patentee’s actual damages. Recklessness in this instance means that there was a high likelihood that an activity would result in patent infringement. Thus, for example, if a client is aware of a competitor’s patent, but regardless offers a competing product or service, a court may find that the client engaged in willful infringement. However, a competently written non-infringement opinion provides a defense against a claim of willful infringement.

It is important to understand that if an infringement opinion is sought, the client cannot blindly rely upon it as a shield to accusations of infringement. The infringement opinion must have indicia of competency, such as the competency of the practitioner providing the opinion (Is the opinion provided by a patent attorney with experience in infringement matters and relevant patent law?), the completeness of the opinion (Does it include a review of the prosecution history of the patent or patents of concern?), the factual and legal accuracy of the opinion, and reasonableness of the opinion’s conclusions (Does the opinion claim there is no possibility of infringement?). Also, in order to use the infringement opinion as a defense to willful infringement, the client must review the opinion and verify that it is reasonable and competently prepared. Of course, the client must also follow the guidance in the infringement opinion.

An additional benefit of a freedom to operate search is that search results and analysis provides the patent landscape surrounding the new product or service. This knowledge is critical not just for navigating potential infringements, but also for evaluating the patentability of the new product concept. The understanding of the patent landscape allows for evaluation of the novelty and non-obviousness of the new product idea under US patent law. A determination as to whether patent protection is available is also highly valuable information for product development strategy. If there is a good chance of patentability, a patent application may be pursued. Mapping the patent landscape through the freedom to operate analysis ensures that the new product not only avoids infringement of existing patents but also informs the business of its own patent prospects.

Entrepreneurs are constantly innovating and realizing new product ideas. However, as part of their product development process, they need to vet their new product or service for potential conflict with third party patent rights. Infringement analyses are important due diligence tools for keeping clients out of costly litigation situations when they are trying to deliver an innovative product idea to customers. The risk of patent infringement should always be on the minds of product development teams and entrepreneurs when they are contemplating a new product or service offering. Patent litigation is a painstaking and highly expensive process. An ounce of due diligence and patent infringement analysis prevention can avoid massive patent litigation pain.

US patent law provides for exclusive rights in an original ornamental design through issuance of a design patent. The primary focus of a design patent is not the functional features of a product but rather its ornamental features. The "claimed design" must be novel and non-obvious in its ornamental aspects. The protection it offers is limited to the appearance of the item as depicted and claimed in the patent drawings.

A design patent application may include multiple versions or embodiments of the claimed design. During the patent examination process before the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), a patent examiner may issue a restriction requirement in an application that includes multiple embodiments. This procedural step is rooted in the principle that each design patent application should cover only a single claimed design. If designs are not substantially similar, they may be divided into separate filings. This requirement ensures that design patents issue for a single ornamental design.

Applicants faced with a restriction requirement have the option to pursue each segregated design through a divisional application. This allows the patent applicant to continue seeking protection for all originally presented designs. However, a restriction requirement may create prosecution estoppel (or file wrapper estoppel) that can impact the rights of the patent owner.

Since the Federal Circuit’s decision in Pacific Coast Marine Windshields in 2014, patent attorneys have been wary of the potential consequences of filing design patent applications including two designs or more. In Pacific Coast, the court held that under the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel, when a design patent applicant agrees to elect specific embodiments in response to a restriction requirement, the unelected embodiments fall outside the scope of a design patent that issues from the application. Generally speaking, the issuing design patent cannot be successfully asserted against a third party practicing the non-elected embodiment. In the wake of the Pacific Coast case, it became clear that divisional design patent applications must be filed in order to secure patent rights in any non-elected embodiments.

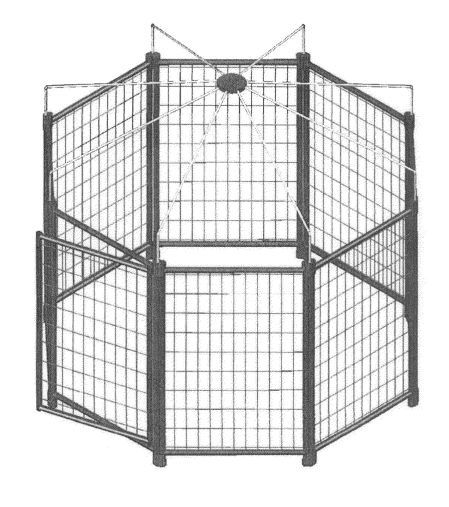

However, in the Advantek Mktg. v. Shanghai Walk-Long Tools Co. case, the Federal Circuit court of appeals was again presented with a design patent case involving prosecution history estoppel arising from a restriction requirement. In Advantek Mktg., Advantek filed suit against its former contract manufacturer (Shanghai Walk-Long Tools Co.), asserting that Walk-Long infringed US Design Patent No. D715,006 covering a portable kennel. The application for the ‘006 design patent was filed with five figures: the first four figures showed an octagonal pet kennel design without a cover, and the fifth figured showed the same octagonal design with a cover. The patent office found that the application included more than one design and issued a restriction requirement in the application identifying two distinct embodiments – (1) the first four figures as a subcombination and (2) the fifth figure as a combination – and required the election of one of the embodiments. Advantek elected the first embodiment as shown in the first four figures (the kennel with no cover).

The allegedly infringing kennels sold by Walk-Long included a cover. Walk-Long filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings under 12(c) asserting that the scope of the ‘006 patent excludes a kennel design with a cover under the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel as a result of the election made during the examination of the application for the ‘006 patent. The US District Court for the Central District of California granted judgment on the pleadings, agreeing with Walk-Long that prosecution history estoppel barred Advantek’s claim.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed and remanded in spite of the prosecution history estoppel. Advantek successfully argued that, even though it had surrendered the embodiment of the kennel that included a cover, the kennel sold by Walk-Long necessarily includes the design covered by the ‘006 patent because it is a “skeletal structure” onto which a cover can be added. The Federal Circuit agreed, pointing to the US Supreme Court’s recent decision in Samsung Electronics Co. v. Apple Inc., in which the court affirmed that a design patent can cover a component of a larger product and that such design patent can be infringed by a product that incorporates the patented design. The court stated that:

The Federal Circuit accordingly concluded that Advantek was not estopped from asserted the ‘006 patent against Walk-Long.

While this case reiterates the potential dangers of surrendering embodiments in design patent applications, it also shows that the scope of the surrendered subject matter can be narrow. The outcome in this case is not unlike the Pacific Coast case, in which it was held that the accused design fell within the scope of the asserted patent, even though some of the embodiments in the plaintiff’s patent application were surrendered as a result of a restriction requirement. The surrendered design in that case was a boat windshield design having two holes therein, whereas the asserted design patents covered boat windshield designs with no holes and four holes. The Federal Circuit concluded that the patentee had surrendered only the two-hole and not the accused three-hole design, and that prosecution history estoppel did prevent the plaintiff from asserting infringement based on the three-hole design.

In both the Pacific Coast and the Advantek Mktg. cases, the subject matter surrendered and subject to prosecution history estoppel was very narrow in scope. In fact, in the Advantek Mktg. case, the scope elected embodiment of the ‘006 patent essentially swallowed the scope of the surrendered embodiment. The two embodiments were a combination and subcombination. In such situations, it seems intuitive that the broader subcombination should be elected, barring other considerations. However, even though it appears that prosecution history estoppel resulting from restriction requirements and elections of species may have a limited impact on the scope of a design patent, patent practitioners should remain wary of its potential threat and thoroughly consider filing divisional applications to cover the withdrawn embodiments or species.

A trademark (word, name, symbol, sound, or design) is a source identifier for goods and/or services that are provided in connection with the mark. The trademark serves to indicate to the consumer the likely quality and character of the goods or services based on the reputation the trademark owner has built in the marketplace. For example, everyone recognizes that the Nike company makes athletic shoes of a high quality, and consumers expect to get a certain level of quality from a pair of shoes marked with the word NIKE. This reputation is built through the use of the NIKE trademark in connection with its quality products. But when does trademark protection begin? It is common misconception that one can protect a word, phrase, and/or graphic as a trademark or service mark once it is created. Under US trademark law, trademark protection does not begin until a mark is “used in commerce”. The Nike company was not able to register its NIKE trademark for use on shoes until it actually began selling shoes to consumers. Trademarks protect both the consumer looking for reliable goods and services and the trademark owner’s business and reputation that it has built through the provision of quality goods or services.

Use in commerce is defined as a mark placed on goods (e.g., on the container, label, tag, packaging, or point of sale display) or presented in connection with services (e.g., on business cards, advertisements, and websites) that are sold or transported in interstate commerce. Interstate commerce, in this sense, means anything Congress can lawfully regulate. Generally, this means commerce across state lines and commerce between the US and a foreign market, or with a substantial connection to interstate commerce that is more than nominal. Solely intrastate commerce does not qualify as “use in commerce” under the Lanham Act (the Federal Trademark Act) and such marks cannot be registered with the USPTO. A local nail salon, grocery store, or the like probably does not use its service mark in interstate commerce. However, if an intrastate business affects commerce that Congress can regulate, it would qualify as “interstate commerce” under the Lanham Act. An example of such a business would be a local travel agency that is booking interstate and/or international travel. It should be noted that intrastate commercial activity does result in common law trademark rights in the geographic area where the business’s goods are sold and/or services are provided.

In order to demonstrate that transactions constitute uses in commerce, the mark must already be present on the goods or in association with the offered services when they are sold or transported to the public. It cannot be placed on the good or associated with the service after the sale or swapped out with another mark after the purchase but before the delivery.

Use in interstate commerce requires an actual sale: typically an exchange of money for a good or service. This means members of the public must be exposed to the mark and choose to purchase the good or service offered under the trademark based on their own choice. Advertising alone is not sufficient. Also, the good or service must actually be available for sale and delivery to the customer.

A sham transaction refers to a transaction crafted solely for the purpose of creating the appearance of genuine sale of a a good or service in connection with the trademark. For example, a trademark owner requests that a friend or employee purchase a newly offered good to establish a sale. In other words, the sale is not a bona fide commercial transaction, even though money has been paid for the good. For a use to be considered "in interstate commerce" US Trademark Law, it must be a legitimate use of the mark in the ordinary course of trade, and not merely to reserve rights in the mark. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and courts look for actual sales of goods or services under the mark to real customers, where the transaction is indicative legitimate commercial activity. It is contrary to the purpose of trademarks to allow ownership rights in a trademark to a party or business that does not legitimately use the mark in connection with goods or services. A sham sale or transaction is usually done to create inauthentic documentation of a sale to circumvent the legal requirements register a trademark with the USPTO. Such actions are scrutinized and often dismissed as attempts to unjustly reserve trademark rights without engaging in real commercial activities. This principle ensures that trademark protection is granted only to marks that are truly used to facilitate commerce and consumer recognition in the marketplace.

Advertising, though it exposes the public to the good, without the ability to perform a sale does not constitute use in commerce. This applies to television or radio commercials, paper or billboard advertisements, and online ads and websites. If a website simply displays and advertises a good or service without presenting an ability to purchase it, the trademark is not considered to be used in interstate commerce. Also, an internal distribution between a manufacturer and regional managers or a distributor is not a sale or use in commerce. The goods must be presented for public use to potential wholesale or retail customers.

Also, the good or service must be in existence when it is sold. The trademark will not be considered used in commerce until the good physically exists or the service is actually available. The mark needs to identify or distinguish the goods from others’ goods.

The other way goods are used in commerce is through transportation. Transportation also requires the goods to be available for public use. Therefore, in-house experimentation, evaluation or preparation do not constitute bona fide shipments to satisfy the public use requirement. However, if the good is shipped to individuals or groups outside the company, e.g., sending a new drug to clinical investigators, this may constitute transportation use in commerce.

The USPTO may allow businesses distributing promotional gifts, free services, or free samples a registration of their trademark. However, any giveaways will usually need to be connected to selling the good or service in the future. Additionally, they may allow goods transported for a sale presentation to potential customers to qualify as use in commerce. Typically, any imported or exported goods will meet the use in commerce requirement. No matter how the goods are transported or what type of goods they are, the mark owner must authorize any transportation through interstate commerce.

An intent-to-use (ITU) trademark application under Section 1(b) of the Lanham Act allows an entity to apply for trademark registration before it has actually begun using the trademark in commerce. An ITU application serves specific purposes and has distinct requirements.

An ITU application is a strategic tool for securing trademark rights in the United States and requires careful planning and timely action to move from an intent-to-use basis to actual use in commerce to achieve registration.

A trademark must be used in at least one commercial transaction in order to generate trademark rights and justify a federal registration for the trademark. This requires the good or service to be available to the public and exist at the time of sale. Advertising alone will usually not meet the use in commerce requirement. An online website must have the capability of selling the good or service on the webpage. Any transportation of a good or service must be for the purpose of selling the product and the goods and services must be provided in connection with the trademark. However, a business or entrepreneur may get some early protection of a trademark by filing an ITU application prior to using the trademark in commerce, if they have a bona fide intent to use the mark in commerce.

© Sierra IP Law, PC – Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights 2022. The information provided herein is not intended to be legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the legal professional community, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

At a time when the health of the U.S. economy and creating and maintaining U.S. manufacturing jobs are top of mind, the “Made in the USA” claim on products resonates among consumers. The claim communicates the entrepreneur’s efforts to create or preserve American jobs. While the value of an origin claim from the U.S. is clear, a product must first clear the legal hurdles to use the coveted “Made in the USA” label. This article addresses the standards for claiming a product as “Made in the USA” under Federal and California law.

Federal Law

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is the agency responsible for policing origin claims in the marketplace. FTC standards are therefore the primary determinant as to whether or not a claim of US origin has been properly made. The FTC’s regulations distinguish claims of US origin into two categories: unqualified claims and qualified claims, both of which are subject to different requirements.

Unqualified Claims

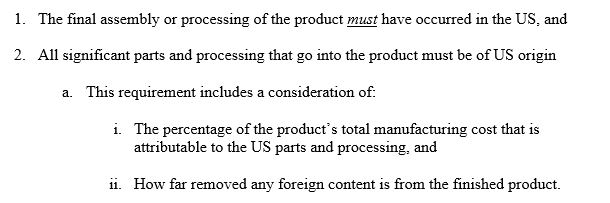

A product claiming its origin is the US without qualification, such as in the basic “Made in the USA” label, is considered an unqualified claim. Non-explicit, implied claims of US origin like a US flag or map may also be considered an unqualified claim of US origin. Because there is no qualification to the origin claim, consumers assume such a product is made entirely, or nearly entirely, within the United States. The FTC incorporates this consumer assumption into their test for unqualified claims. The agency requires an unqualified claim of US origin to be substantiated with evidence that the product is entirely or virtually entirely made within the US. The standard is somewhat vague, but there are two requirements that are considered in determining whether an unqualified claim is lawful:

The first requirement is a clear standard. The second requirement needs some explanation. With regard to factor (i), there is no set percentage threshold of a product’s total manufacturing cost that must be attributable to US parts and processing. Instead, determinations are made on a case-by-case basis and involve a consideration of foreign versus domestic costs, the nature of the product, and consumer’s expectations. With regard to factor (ii), the earlier in the production process that foreign content is included, the less significant that content is considered to be to consumers. For example, the origin of raw materials in electronics, such as rubber wire coating made from petroleum extracted in Africa, is likely not meaningfully proximal to the final assembled product and may therefore be of little to no importance to the unqualified claim. When evaluating an origin claim, each factor and relevant circumstance must be carefully taken into consideration to determine whether the product can be labeled “made in the USA” without qualification.

Qualified Claims

A product that does not meet the “all or virtually all” standard must qualify its claim of US origin. These claims are subject to less stringent requirements than those applied to unqualified claims. A qualified origin claim must disclose the extent, amount, or type of constituents in the product that were domestically made in a prominent and clear manner – e.g., “Sheets manufactured in the USA from Indian cotton”. An accurate description of US and foreign components comprising the product will generally allow for a qualified US origin claim to pass muster. The language used in the qualified origin claim must be sufficiently accurate to avoid a likelihood to deceive consumers. Products that are only partly assembled in the USA cannot include a general phrase that suggests that the entire product was “assembled in the USA”. The unqualified claim must be more specific. For example, if a computer is assembled in the US from components that were made and assembled overseas (e.g., a hard drive made and assembled in China), the qualified claim should be something like “final assembly in USA”.

While the requirements set forth by the FTC are reasonably comprehensible, they are not the only regulations that must be considered. State laws, while often mirroring the FTC rules, provide further requirements for US origin claims to be used within each state. This article addresses California as an example.

California Law

The purveyor of products in California with a claim to hail from the US must satisfy both California law and FTC regulations. In contrast to the FTC, California law takes a singular approach to regulating claims of US origin. The California standard makes no distinction between qualified and unqualified origin claims.

The governing California statute, Business & Professions Code section 17533.7, applies to products sold in California. The statute permits a product to use a US origin designation in California, if foreign content represents no more than 5% of the final wholesale value of the product (Bus. & Prof. 17533.7(b)). This requirement is wholly determinative of the validity of a US origin designation in California with one exception: foreign content can represent up to 10% of the final wholesale value of the product, if some of the parts or content of the product cannot be obtained within the United States. California’s test is more straightforward than that of the FTC, but both standards must be observed for any products sold in California. If a business sells goods in multiple states with a claim of US origin, it would potentially have to juggle several standards if the product was not 100% made in the US. Thus, purveyors of goods should be wary of the particular standards in the markets they serve.

© 2021 Sierra IP Law. The information provided herein is not intended to be legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the legal professional community, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

CASE Act

As part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act for 2021 signed into law on December 27, 2020, the Copyright Alternative in Small-Claims Enforcement (CASE) Act was passed. The CASE Act establishes a tribunal called the “Copyright Claims Board” (CCB) within the U.S. Copyright Office to handle small-scale claims of copyright infringement. Copyright registrants can use this option to pursue smaller copyright infringement matters in a more streamlined and lower cost process. The hearings may be conducted electronically, making CASE proceedings attractive and available to many small claimants.

The Board will be made up of three members, and will have two supporting attorneys. At least two Board members must preside at any hearing. Discovery is limited to interrogatories, requests for admissions and production of documents. Any other type of discovery requires a showing of good cause. An accused infringer will have 60 days after service of a claim to “opt out” which will result in dismissal of the claim without prejudice, requiring the claimant to file in District Court. However, there are incentives for both sides to use the CASE system: it should be faster and cheaper for a claimant, and it provides a low limit of potential liability for an accused infringer.

Awards for infringement of a single work are limited to $15,000 (instead of the $150,000 limit in District Court); and awards for infringement of multiple works in a single proceeding are limited to $30,000. The plaintiff can pursue actual or statutory damages up to the monetary limits, but willful infringement is not considered and cannot be used to enhance the damages award. Attorney fees and costs are generally not available except in cases of bad faith, and in those cases are capped at $5,000 unless the conduct was particularly egregious.

A party can request reconsideration of a CCB decision if the party believes the CCB’s decision includes error. If the CCB accepts the request, the decision is reviewed for clear error. A party can seek review of the CCB’s decision with the Register of Copyrights. The CCB decision is reviewed for abuse of discretion by the Register of Copyrights. After review by the Register of Copyrights, a party can seek relief from the appropriate district court in very limited circumstances: where the CCB decision resulted from fraud, corruption, or other misconduct, the CCB exceeded its authority or failed to provide a final judgment, or a default or failure to prosecute judgment was entered resulting from excusable neglect by the party seeking relief.

A CASE claim may be based on a pending copyright application prior to the issuance of a registration. However, any decision on the claim will not be final until after the registration is obtained. A CASE claim may not be filed without a copyright application submitted to the US Copyright Office. The CASE system may be attractive to owners of multiple copyrighted works who may be able to avoid the high cost of litigation in District Court. However, this may be restricted since the Register of Copyrights has the authority to place limits on the number of cases that the same claimant may be allowed to bring each year.

PLSA

The Protecting Lawful Streaming Act raises the criminal penalties for illegally streaming copyrighted material from a misdemeanor to a felony for certain defendants. The felony penalty does not apply to unauthorized streamers in general. Instead, the felony penalties will apply to a streaming service that is intentionally designed to stream copyrighted works without permission. The PLSA was drafted to provide stronger penalties to go after bad actors, while sparing unsophisticated and small-time offenders (e.g., a fan live streaming a concert without authorization).

Sierra IP Law will provide further guidance on these laws as they are implemented, and advise and assist its clients in utilizing the new tools provided by the CASE act. Contact Sierra IP Law for guidance with regarding to copyright matters.

© 2021 Sierra IP Law. The information provided herein is not intended to be legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the legal professional community, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

In the modern commercial world, practically every business sets up a web site, which means that the business must also select a domain name. It is often desirable for the business to select a domain name that is the same as its business name, trademark or service mark, in order to help the consuming public find the products or services of the business on the Internet. The US Supreme Court recently made it a bit easier to register a domain name as a trademark.

Prior to June 30, 2020, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) did not allow domain names to be registered as trademarks if they contained words that were generic as to the goods or services provided, since generic words cannot function as trademarks. A top-level domain (TLD) suffix such as “.com” or “.net” was also considered generic in the same way as suffixes such as “Co.” or “Inc.” Under this rubric, the USPTO considered that when a generic word is combined with a generic TLD suffix in a domain name, the result was also generic, and therefore not registerable as a trademark. This approach was eliminated on June 30, 2020, in a ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of US Patent and Trademark Office, et al v. Booking.com B.V.

The Booking.com decision may be better understood after a brief review of trademark principles. A trademark is a word, symbol or device that is used in commerce in connection with goods. (A service mark is used in connection with services, but references in this article to “trademark” are meant to include service marks.) The function of a trademark is to help the consuming public identify the source of particular goods or services. US trademark law recognizes that there is a spectrum of trademark protection ranging from marks that are legally strong to those that are legally weak, and those that cannot be protected at all. Strong trademarks are those which are arbitrary, fanciful or suggestive with respect to the goods or services they are used on. Descriptive terms are usually not entitled to trademark protection, but can become enforceable over time as the public learns to associate the descriptive mark with the source of goods or services provided under the descriptive term (e.g., think American Airlines, National Football League, etc.). Generic terms, on the other hand, are never available as trademarks because they cannot act as source identifiers, since their primary function is to identify classes of goods or services.

In the Booking.com case, the USPTO had concluded that “booking” was a generic term for its services of “making travel reservations” and that the “.com” TLD suffix was also generic since it only served to identify a commercial website. The USPTO therefore concluded that the combination of “Booking.com” was not registrable because the combination was generic or, in the alternative, that it was descriptive without secondary meaning. The USPTO decision was first taken to the District Court, then to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, and finally to the US Supreme Court. In an 8-1 decision authored by Justice Ginsburg, the Supreme Court held that a term styled ‘generic.com’ is a generic name for a class of goods or services only if the term has that (generic) meaning to consumers. Thus, adding a TLD suffix (such as “.com”) to a generic word (such as “bookings” for “making travel reservations”) could be registerable as a trademark under the proper circumstances, and that simply combining a generic term to a TLD suffix alone did not disqualify the combination from being registered. The USPTO argued that a TLD suffix is generic like entity signifiers “Inc.” and “Co.” However, the court found that a TLD suffix is not sufficiently similar to such generic identifiers because each domain name is unique, and (unlike “Inc.” and “Co.”) only one entity can use a particular domain name. Thus, the court found a ‘generic.com’term could convey to consumers an association with a particular website – which is the source identification function of a trademark. However, the decision made note of numerous limitations already in place under trademark law, including a requirement that the domain name overcome any descriptiveness issues (e.g., by establishing secondary meaning). Thus, to register a ‘generic.com’ domain name, it will need to be shown that the domain name has established secondary meaning to overcome descriptiveness issues, and that consumers have come to associate the domain name with the business as the source of the goods or services, instead of simply identifying that class of goods or services. Extensive advertising was submitted in the Booking.com case (e.g., “Booking.com, booking.yeah!”, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tk_pFjr5aV4), helping the court conclude that it had established secondary meaning in the mind of the consumer for the Booking.com mark.

Of course, it is easier to register and enforce trademark rights in terms that are neither generic nor descriptive, so a business owner should avoid selecting generic or descriptive terms for its trademarks, business name, and domain name if that is possible. An effective trademark should not only aid in attracting clients and customers, it should also provide the business with enforceable trademark rights that allow the business to prevent competitors from using confusing similar terms and phrases to promote their businesses. However, if a descriptive or generic term has already been selected for the domain name, the Bookings.com case leaves the door open for the owner of such a term to protect it as a trademark.

Sierra IP Law assists businesses with evaluating their existing or proposed trademarks and service marks, and works with its clients to find effective, enforceable, and registerable marks that will serve them well. If you have questions about trademarks, visit our trademark FAQ page, general trademark page, and our trademark registration page.

© 2020 Sierra IP Law. The information provided herein is not intended to be legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the legal professional community, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

On Sunday, December 27th, President Trump signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act for 2021. As part of the legislation, the Trademark Modernization Act (TMA) was passed as well. The TMA imposes several significant changes on US trademark law. The TMA is the most sweeping trademark legislation in decades and has several important features that trademark and business owners should note.

Two of the changes provide new and apparently more efficient tools for cleaning up the federal trademark register. First, the TMA allows third parties to initiate ex parte procedures (expungement or re-examination) to remove trademark registrations for marks that were never in proper use. This will allow persons and entities pursuing registration of their legitimate marks to clear out (1) zombie registrations for marks that are no longer in use and (2) faulty registrations for marks that were never properly in use. In particular, these tools will allow deserving trademark holders to remove foreign priority applications (Section 44 applications) that often create barriers to registration for domestic trademark applicants. Section 44 registrations do not require demonstration of use in commerce, and frequently include long lists of goods or services that will probably never be offered in marketplace. The TMA provides tools to address these unfortunate side effects of foreign-based registrations.

Second, the TMA allows third parties to intervene and submit evidence in a pending application to demonstrate that the application should be refused (e.g., because it is confusingly similar to intervener’s mark). This will allow those with legitimate prior rights to (1) intervene in a third party’s attempt to register a confusingly similar mark and (2) perhaps avoid the expense and delay of a formal opposition proceeding at the Trademark Trial and Appeals Board (TTAB).

Additionally, the TMA strengthens the legitimate trademark holder’s ability to police and enforce its rights by making injunctive relief more attainable. The TMA establishes a rebuttable presumption that a meritorious trademark plaintiff has sustained irreparable harm. This reverses a trend established by the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in eBay v. MercExchange, 547 U.S. 388 (2006). Since the eBay case, it has become challenging for trademark plaintiffs to obtain an injunction. Under the TMA, plaintiffs who have successfully proven infringement or have demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits, will have an easier path to permanent and/or preliminary injunctions. This will increase the value and protection of trademark registrations and trademark rights generally, as the trademark holder will have much improved prospects of shutting down infringing use.

Finally, the TMA gives the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office director "the authority to reconsider, and modify or set aside, a decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board." This change heads off a constitutional challenge to the appointment process for TTAB administrative law judges (ALJs) based on the Federal Circuit's decision in Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc., 941 F.3d 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2019). In Arthrex, the Federal Circuit found that the appointment of Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB) ALJs by the Secretary of Commerce is unconstitutional because the PTAB ALJs are principal officers under the Appointments Clause. Principal officers must be appointed by the President. The Arthrex case is currently pending before the Supreme Court.

Sierra IP Law will advise and assist its clients in utilizing the new tools provided by the TMA to challenge unwarranted and abandoned trademark filings.

© 2020 Sierra IP Law. The information provided herein is not intended to be legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the legal professional community, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney