Very few people outside of the copyright legal community understand the difference between a work’s copyright date and its publication date. It is an important distinction with significant legal implications under U.S. copyright law. In simple terms, a copyright date usually refers to the year the copyrights in the work came into being (this varies depending on when the work was created and published), while the publication date is the date the work was first made available to the public. This article breaks down the differences between a copyright date and a publication date, explains how U.S. copyright law treats each, and discusses the practical implications of each across the relevant U.S. copyright acts: the Copyright Acts of 1909, the Copyright Act of 1976, and the Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988. The article's purpose is to help creators, publishers, and businesses better understand the importance of these dates and enable them to protect their creative works.

U.S. copyright law protects original works of authorship as soon as they are “fixed in a tangible medium of expression,” meaning the moment you write down your story, record a song, or save your painting to a canvas, it is automatically protected by copyright. Under current law, you do not need to publish the work or register it with the government for the copyright to exist; the act of creation itself grants the author exclusive rights over the work under copyright law. These exclusive rights include the right to reproduce the work, distribute it, create derivative works, publicly perform or display it, and license others to do the same. Any use of the work by others without permission that falls outside legal exceptions (such as fair use) may constitute copyright infringement, regardless of whether the work has been published or not. Thus, a creative work is protected from the moment of creation, long before any formal publication date or registration date. However, publication and registration are still very important in determining the legal standing and the scope of copyright protection for a particular work.

In everyday language, “publication” often means the publishing date or release date of a book, article, or other work. But in U.S. copyright law, publication has a specific technical definition. Publication is generally defined as “the distribution of copies or phonorecords of a work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending”. Importantly, even offering to distribute copies to a group for purposes of further distribution or public performance constitutes publication, whereas a mere public performance or display (e.g., publicly displaying a painting in a gallery) does not, by itself, constitute publication. In practical terms, publication occurs on the date when copies of the work are first made available to the public without restrictions. For example, if you print and sell a batch of books or release a new song on a streaming service, that act typically counts as publication because copies are being distributed to the public by sale or other transfer. By contrast, if you simply show a painting in a private exhibition or perform an unpublished song live, those acts are not considered publication under copyright law’s definition.

Understanding what constitutes publication is crucial because many aspects of copyright law hinge on whether and when a work was “published.” The date of first publication triggers certain legal obligations and affects the rights of the copyright owner, as discussed below. We will examine how publication plays a role in copyright duration, registration, notice, and the work’s entry into the public domain, and how those implications have changed across different eras of U.S. copyright law.

The term “copyright date” is not explicitly defined in the statute, but it is commonly used to refer to the year associated with a work’s copyright. Typically, the copyright date and the date listed in the work’s copyright notice used to be the same thing, but with the changes that came with the US implementation of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works in 1988, which amended the 1976 Copyright Act. As of March 1, 1989, the notice requirement to establish and maintain copyrights upon publication of a work. Copyright notice is now optional.

A copyright notice is the line that often begins with © (the copyright symbol) and is usually found on the copyright page or title page of a published work (for example, “© 2025 John Doe”). By convention, this year in the notice is the year of first publication of that work. For instance, if a novel was first published in 2025, its copyright notice would normally read “© 2025 [Author/Publisher Name].” The copyright date on the notice informs the public when the work was first released and who the copyright owner was at that time. Business owners should note that the copyright year is typically found in books, on websites, and other creative works to signal when the work was published and that it is protected by copyright law.

It’s important to understand that the copyright notice year is not necessarily the year the work was created. If an author finished writing a creative work (e.g., a manuscript) in 2024 but waited until 2025 to publish it, the publishing date (first publication date) is 2025. However, the copyrights were established in 2024. Sometimes, multiple dates are listed in a copyright notice because of changes to the content of the particular work. For example, if a website’s content is continually updated, the site might display a range of copyright years (e.g., “© 2018–2025”). The changes in the content do not result in the earlier content losing protection, it simply indicates the site includes material up to the current year. The copyright date in the notice serves as an informative date and helps in determining the term of protection for certain works, especially for works made for hire or anonymous works where the term is measured from publication. The copyright date, however, is complicated by changes to copyright law over the course of the twentieth century. Due to the long duration of copyright term and the relative recency of the changes in copyright law, there are currently co-existing works that are subject to different legal regimes based on when they were created and/or published. In older works, the publication date determines the copyright date. These nuances are discussed in further detail below.

Today, including a copyright notice and thus a visible copyright date on published copies is optional but recommended. U.S. law no longer requires a notice to obtain copyright protection. That requirement was eliminated in 1989, but using one has practical benefits. A proper notice informs the world that the work is copyrighted, names the copyright owner, and states the year of first publication, which can prevent an infringer from claiming they didn’t realize the work was under copyright: the “innocent infringement” defense. For works published before March 1, 1989, a valid copyright notice was mandatory, and publishing without a notice could cause the work to enter the public domain immediately. In summary, the copyright date on a work is a public identifier of the work’s first publication year and its claim of copyright. It is not necessarily the date the copyright registration was obtained, since copyright exists upon creation, and thus should not be confused with the date of registration or the exact calendar date of release.

The publication date of a work is the date when the work was first published, as defined by copyright law. In everyday usage, this might be the book’s release date, the date a website or article went live, or the day a music album was released to the public. Legally, the publication date is significant because it’s a fixed point in time that the law uses for several purposes. Generally, one can think of the publication date as the moment the copyright “goes public”: it’s when copies are first made publicly available without restrictions. This date can often be found in the front matter of a book (e.g., “First published in [Month Year]”) or in a record of the publisher. For a website or an online content piece, the publication date might be evident from the posted date or release notes.

It’s worth noting that for many works, the copyright notice year and the first publication year are the same, since the notice reflects the year of first publication. However, the actual full publication date (month and day, or at least month and year) can be important in certain legal contexts. For example, an application to register the work should be filed within three months of the publication date, and thus an accurate publication is needed to calculate a three-month window. Also, different editions or versions of a work can have different publication dates. For instance, if a particular work, such as a book, was first published in 2010, that is the key publication date for copyright purposes. A different book (e.g., a revised edition or a translation of the 2010 book) published in 2015 would have 2015 as its publication date and its own notice year, even if the underlying text was first created earlier. Business owners publishing content should always keep track of the exact first publication date of each work, as this date can affect the duration of copyright and certain legal rights and obligations.

In scenarios where a work was created but not immediately published, the creation date and the publication date diverge. For example, imagine a photographer took a photograph in 2015 but publicly released it for the first time in 2021. In this case, the copyright existed from 2015 (creation), but the publication date is 2021, and that 2021 date would be critical for the copyright application deadline. The publication date is essentially when the work “officially” enters the marketplace or public sphere, which has downstream effects on how the Copyright Office and courts treat the work.

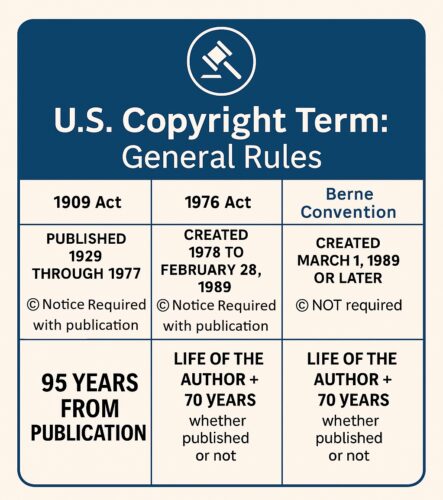

Under the Copyright Act of 1909, which governed U.S. copyright law for works created before 1978, publication was of paramount importance. At that time, federal copyright protection typically began at the moment of publication, assuming the work was published with the proper notice. In fact, if a work was published in the United States without a proper copyright notice under the 1909 Act, the work could instantly fall into the public domain, meaning anyone could use it freely. By contrast, unpublished works were protected by state common law copyrights (a form of protection in equity) until they were published. Publication was the act that triggered federal statutory protection: an author would publish the work with a © notice, and from that date of publication the author had copyrights for a set period of years. Under the 1909 Act, the initial federal copyright term was 28 years from the date of publication with an option to renew for another 28 years. This means the publication date started the clock on the copyrights' duration. If the copyright owner wanted to extend protection beyond the initial term, they had to file a renewal registration in the final year; failing to renew would cause the work to enter the public domain at the end of the initial term.

To illustrate, suppose a book was first published with notice in 1940. Under the 1909 Act regime, its federal copyright would run 28 years from 1940 to 1968 and could be renewed to run for a second 28-year term until 1996. The key point is that the publication date was essentially “day one” of copyright protection under the old copyright law. An unpublished work prior to 1978 had no federal copyright term running because it wasn’t in the federal system until publication. This is a stark difference from modern law.

Also, the requirement of a notice on the published copies meant that the copyright date printed on works (e.g. © 1940) had real legal weight; it indicated that the work was properly claimed under the 1909 Act on that publication date. A missing or incorrect notice could be fatal. As a famous example, the publishers of the film Night of the Living Dead (1968) accidentally omitted the notice when the title was changed at release, causing that otherwise original film to enter the public domain immediately.

It’s also worth mentioning that under the 1909 Act, many works that were not published at all remained under perpetual common-law protection until they were eventually published. This changed with the 1976 Act, which we discuss next. But for our purposes here: if you are dealing with a work first published before 1978, the publication date and whether proper notice was used were critical in determining if the work was copyrighted, for how long, and whether it might have fallen into the public domain due to missed formalities. Attorneys handling legal disputes over older works often must research the publication history and notices of a work to determine its copyright status.

The Copyright Act of 1976, which took effect January 1, 1978, overhauled U.S. copyright law. One of the biggest changes was that copyright protection no longer depends on publication or registration. Instead, copyright protection is automatic from the moment of creation (fixation), and publication is not required to secure copyrights. This brought the U.S. closer in line with international norms, such as the Berne Convention. Under the 1976 Act, works created on or after January 1, 1978 are protected for the author’s life plus 70 years for individual authors, regardless of when or if the work is published. In terms of when the law says copyright protection starts, the copyright date is now the date of creation, not publication. You could write a story today and never publish it; it would still be a copyrighted work until it eventually expires many decades later.

In 1988, Congress passed the Berne Convention Implementation Act, which took effect on March 1, 1989. This legislation eliminated the requirement that published works include a copyright notice in order to receive federal copyright protection. Prior to that date, omission of a proper notice could result in immediate forfeiture of copyright protection for published works under the 1909 and 1976 Acts. After March 1, 1989, notice became optional, but still recommended, for works first published in the U.S. This amendment was essential for U.S. adherence to the Berne Convention, which prohibits signatory countries from conditioning copyright protection on compliance with formalities such as registration or notice.

The publication date still remains very significant under the 1976 Act and its amendments, but in different ways. For example, for works made for hire or anonymous/pseudonymous works, often owned by companies or published under a corporate name, the copyright term is defined as 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first. In these cases, the year of first publication can indeed determine the length of protection. If a company creates a work and publishes it immediately, the clock runs 95 years from that publication year. If the company never publishes the work, the term would max out at 120 years from creation. Thus, even in the modern regime, knowing the exact first publication date is essential for calculating when a work will enter the public domain for certain types of works.

Additionally, the 1976 Act and subsequent amendments preserved special rules for works that were created before 1978 but not yet published by that date. Section 303 of the current law provided that pre-1978 unpublished works were given a default term lasting at least until 2002, and if such a work was first published between 1978 and the end of 2002, it wouldn’t expire before 2047. This was to ensure that older manuscripts, letters, or artwork that remained unpublished as of 1978 didn’t suddenly lose protection. In essence, Congress gave those works a window to be published without penalty. The details are complex, but the key takeaway is that for certain older works, the first publication date can affect whether the work is still under copyright today.

In summary, under modern U.S. law, the publication date does not start copyright protection, since protection starts at creation, but it does trigger other legal effects. Among these are the requirement to deposit copies with the Library of Congress, the timing of registration relative to publication, and the applicable duration for certain works. Also, as mentioned earlier, after 1978 the law gradually eliminated formalities like the notice requirement. So while you might still see a “© 2025” on a book’s title page as the copyright date, that is there to inform and deter infringers, not as a condition of protection. The copyright owner is still wise to include it, as it helps identify the owner and year for anyone who needs to seek permission to use the work, and it may ward off claims of innocent infringement. But if somehow the notice is omitted on a work first published after 1989, the work is still protected: omission no longer forfeits copyright.

It is important to distinguish copyright registration from publication. Registration is the process of filing a claim with the U.S. Copyright Office, and it results in a certificate with an official effective date of registration. This date is essentially when the Copyright Office received all required materials in the proper form. Many people casually refer to “registering a copyright” or getting a “copyright date” from the government. In reality, registration is optional for copyrights to exist, but it is mandatory if you want to enforce your rights in U.S. court and enjoy the full benefits of copyright protection. Think of registration as a way to strengthen and activate your copyright’s legal standing: you already have the copyright upon creation, but you cannot sue for copyright infringement in the U.S. until you have either registered the work or at least applied and been refused registration.

The copyright registration date does not need to coincide with the publication date. You can register an unpublished work, or you can register after publication. For example, a photographer might publish a photo on their website today, but wait to file an application to register copyrights in the photo with the Copyright Office next month. The application date becomes the effective date of registration, if the registration issues. Ideally, authors and businesses should register their works promptly, because registration timing has practical implications. If a work is registered before an infringement or within three months of publication, the copyright owner is eligible to seek statutory damages and attorney’s fees in an infringement lawsuit. If you wait longer than three months after first publication to register and someone infringes in the meantime, you might lose the chance to claim those enhanced remedies for that period of infringement. You could still stop the infringement and get actual damages, but statutory damages are a powerful remedy you’d forgo if registration was not timely.

To put it plainly: the publication date is when the world first sees your work; the registration date is when you officially record your claim with the U.S. government. The law rewards timely registration relative to publication. The Copyright Act provides a three-month grace period after first publication during which you can file for registration and still be able to recover full remedies (statutory damages and fees) even if the infringement began in that window. This is why you’ll hear advice such as “register your work within 90 days of publication.” It’s not because copyright protection would lapse, but because your legal remedies in court can be limited if you miss that window. In order to take advantage of the full benefits of copyright registration, your works should be registered at the earliest opportunity.

Another connection between registration and publication is evidentiary: if you register within five years of first publication, your registration certificate will serve as prima facie evidence of the validity of the copyright and the facts stated in it, in any court dispute. This means courts will presume your claims (e.g., authorship and ownership) are true, putting the burden on others to prove otherwise. Registering many years after publication can weaken that presumption. Thus, while the copyright date in the notice is mostly for informing the public, the registration date is crucial for legal enforcement.

The publication date of a work can also influence how long the work remains protected, i.e., when it enters the public domain. The rules differ based on the type of work and when it was created. As noted, for individual authors under today’s law, the term is life of the author plus 70 years, and publication date doesn’t change that. For example, if a company released a training video in 1980 as a work made for hire, the copyright would last through 2075 (95 years from 1980). If that video was created in 1980 but not published until 1990, then 95 years from 1990 (i.e., until 2085) would be the term, unless 120 years from creation (which would be 2100) comes first. In that case, 2085 is earlier, so the term ends 2085. The takeaway is that for certain works, both creation and publication dates are needed to determine the exact expiration.

Under older laws, as discussed, works had fixed terms from publication (28 years, renewable to 95). Laws passed in 1976 and 1998 extended those terms. As of today, any work first published in 1929 or earlier is definitely in the public domain in the United States due to expiration of term. For example, works published in 1929 entered the public domain on January 1, 2025, after their maximum 95-year copyright term expired. Each year on January 1st, another year’s worth of works (95 years old) fall out of copyright. This schedule is tied directly to the publication year for works from 1923 through 1977, because those works have a term of 95 years from publication (assuming they were properly renewed, etc.). Thus, knowing a work’s first publication date is essential when assessing if it might be public domain. Librarians and researchers often use publication dates as a guidepost for determining public domain status. For instance, as of now, a U.S. book first published in 1930 would be under copyright until the end of 2025 (95 years from 1930), entering the public domain on January 1, 2026, unless something like a missing notice already caused it to fall into public domain earlier.

Conversely, unpublished works were given special treatment so that many of them did not enter the public domain until recently. An unpublished manuscript from 1880, for example, which had never been published or registered, would have been protected by common law until 1978, then got at least until 2002 under the 1976 Act, and if the author was unknown or long deceased, it would have entered the public domain on January 1, 2003 if still unpublished. If it was first published before 2003, it got protection until at least 2047. These examples illustrate that publication dates can extend or limit protection for older works under the transitional provisions. In everyday practice, for works created now, publication date’s main impact on duration is (1) for those work-for-hire/anonymous cases, as noted, and (2) for works from the mid-20th century, the copyrights of which are tied to their publication year.

Beyond duration and formalities, whether a work is considered published or unpublished can affect certain uses and exceptions in copyright law. For example, the fair use doctrine under 17 U.S.C. §107 considers whether a work is unpublished as part of the analysis. Unpublished works get a bit more leeway in favor of the author in some court decisions, as authors have a right to control first publication. Likewise, Section 108 of the Copyright Act provides special rules for libraries and archives: libraries can make preservation copies of unpublished works more freely, since an unpublished work might not be commercially available at all. But for published works, libraries have a different set of rules for archiving and lending. Another example is the right to publicly perform sound recordings via digital audio transmissions (17 U.S.C. § 114); published versus unpublished status can matter for certain statutory licenses. The general theme is that the law sometimes distinguishes between published and unpublished works, granting unpublished works different treatment in certain contexts because distribution to the public has not occurred.

From the perspective of a business or creator, this means that choosing when and if to publish a work can have implications. Once a work is publicly distributed, it is considered published and those special considerations for unpublished works fall away. Additionally, the act of publication might involve other transfers of rights or ownership. For example, if you have a publishing contract, the publisher might become the copyright owner upon publication by transfer. The ownership and licensing arrangements often hinge on publication as well. For example, a photographer might license first publication rights to a magazine. While these issues go beyond just dates, it’s important to see that “publication” in copyright isn’t merely a formality; it is a status that can change how the law treats the work in various scenarios.

Understanding the distinction between copyright dates and publication dates is not just academic, it helps you manage your intellectual property strategically. Here are some practical takeaways and tips:

By following these practices, business owners and creators can ensure their works are properly protected and that they maximize the legal benefits available under copyright law. Always remember that copyright law, while federal and relatively uniform across the U.S., can be complex. The stakes (e.g., in legal disputes over infringement or ownership) can be high when valuable content is involved.

For U.S. business owners and creators, knowing the critical dates for copyright materials is a must to effectively manage intellectual property assets. For further information, the U.S. Copyright Office provides useful circulars and resources. Consulting with a qualified copyright attorney can help to effectively address copyright issues. If you have a copyright matter or other intellectual property issues to address, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney