The issue of gray market goods presents significant legal and economic challenges for brand owners, authorized sellers, and consumers. The gray market, also known as parallel imports, involves the sale of genuine products through unauthorized sales channels. These gray market activities are distinct from counterfeiting, as they involve legally obtained products that are resold in markets outside the authorized distribution channels. While these products are often sold at cheaper prices, they can undermine brand integrity, disrupt a brand's pricing strategy, and impact customer relationships.

This article discusses the legal framework governing gray market goods.

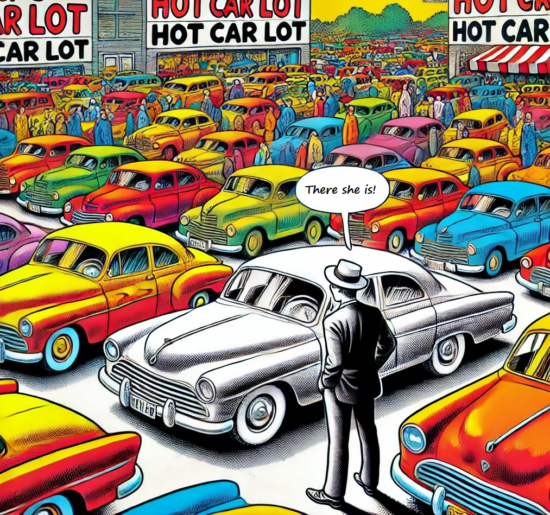

Gray market items are products that bear a valid trademark but are imported or sold outside the official distribution channels established by the brand owner. Unlike counterfeit goods found in the black market, these products are authentic but may not be intended to be sold in specific geographic regions. For example, Chevrolet manufactures vehicles that are intended for foreign markets, such as Canada. If the Chevrolet vehicle is sold into the US, it is a gray market vehicle for the US market. It is not a counterfeit or knockoff vehicle. It is manufactured by Chevrolet for a foreign market, but is still a Chevrolet vehicle.

Gray market goods may differ from their US equivalents in various ways. For example, the goods may have different prices, they may have different features, the branding may differ somewhat, and the products may be manufactured to meet the requirements of a particular country other than the US. In the case of cars, a vehicle manufactured for a foreign country may not meet various requirements for the US market such as the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) and emissions standards set by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Online marketplaces such as Amazon have contributed to a rise in gray market issues. These online marketplaces facilitate gray market sellers, since they provide such a broad international consumer base. Such gray market products originate from foreign countries, which can result in different prices from the US equivalent goods, variations in product quality, and issues with compliance with local regulations.

The regulation of gray market goods involves multiple statutes, including key provisions of the Lanham Act. Courts have addressed the applicability of the Lanham Act to such goods, particularly when the imported products are "materially different" from those intended for the U.S. market.

In Lever Brothers Co. v. United States, 981 F.2d 1330 (D.C. Cir. 1993), the court ruled that gray market goods could violate trademark law if they are "materially different" from authorized products. The case involved imported soap that, although bearing the same trademark as the U.S. version, contained a different formula and lacked assurances of U.S. quality control. The court held that even subtle differences, such as variations in formulation or packaging, could create consumer confusion and diminish the trademark owner's goodwill. Thus, under the "materially different" standard, unauthorized imports that deviate in any meaningful way from the authorized domestic version may constitute trademark infringement.

The application of the Lanham Act to gray market goods underscores the importance of maintaining product integrity and consumer expectations. Trademark owners can rely on these statutory protections to prevent unauthorized imports that undermine their brand reputation and create confusion in the marketplace.

In K-Mart Corp. v. Cartier, Inc., 486 U.S. 281 (1988), the Supreme Court addressed restrictions on parallel market goods that did not meet the "common control" standard. The case involved the importation of goods bearing American trademarks but manufactured abroad without U.S. trademark owner authorization. The Court upheld restrictions on these imports, ruling that Section 526 bars unauthorized parallel imports unless they meet the common control standard. This decision reinforced the principle that trademark owners retain control over their marks and can block imports that do not comply with U.S. quality and distribution standards.

The application of the Lanham Act and the Tariff Act to gray market goods underscores the importance of maintaining product integrity and consumer expectations. Trademark owners can rely on these statutory protections to prevent unauthorized imports that undermine their brand reputation and create confusion in the marketplace.

The first sale doctrine provides that once a trademarked product is lawfully sold, the trademark owner's control over that particular product typically ends, allowing subsequent resale. However, this principle does not apply when material differences exist between the authorized and gray market versions of the product.

The first sale doctrine is a judicially created principle that allows the resale of trademarked goods once they have been lawfully sold. Under this doctrine, a legitimate purchaser of a product may use, dispose of, or resell it without infringing the trademark owner's rights. Courts have ruled that "the right of a producer to control the distribution of its trademarked product does not extend beyond the first sale of the product." Bluetooth SIG Inc. v. FCA US LLC, 30 F.4th 870, 872 (9th Cir. 2022).

However, the first sale doctrine does not protect resellers in all circumstances. Courts have carved out key exceptions, particularly when resales create consumer confusion or when goods are materially different from those sold by the trademark owner. A product is not considered "genuine" if it lacks manufacturer warranties, is repackaged without disclosure, or has altered quality standards.

For example, in RFA Brands, LLC v. Beauvais, No. 13-14615, 2014 WL 7780975 (E.D. Mich. Dec. 23, 2014), the court held that a reseller could not invoke the first sale doctrine without proving that the goods were originally authorized for sale. Similarly, courts have ruled that materially different goods—such as those with altered serial numbers, different formulations, or unauthorized modifications—are not protected under the doctrine. Zino Davidoff SA v. CVS Corp., 571 F.3d 238 (2d Cir. 2009).

Additionally, the doctrine does not shield resellers who falsely imply affiliation with the trademark owner. For instance, businesses that promote themselves as "authorized dealers" or misuse trademarks in advertising may be liable for infringement. The first sale doctrine also does not apply if repackaging or relabeling misleads consumers about the source and quality of the goods.

Thus, while the first sale doctrine limits trademark owners' control over downstream sales, courts recognize exceptions where resale activities undermine brand integrity and consumer expectations. By enforcing these limitations, courts strike a balance between maintaining market competition and protecting trademark owners from unfair exploitation.

Gray market activities can erode brand reputation by introducing products that fail to meet local regulatory or quality standards. For example, cosmetic companies may find that their gray market products lack required labeling or safety compliance for a specific country, leading to consumer complaints or legal repercussions.

Selective distribution agreements allow brands to maintain control over their sales channels, ensuring that only authorized distributors sell products in designated geographic regions. This helps prevent dilution of brand value and preserves the integrity of customer service and warranties.

Gray market goods can differ significantly from authorized versions in terms of quality, warranty, and compliance with local regulations. For instance, electronics brands often include different voltage requirements or software updates that are specific to a region. Consumers unaware of these differences may experience functionality issues or an inability to receive manufacturer support.

Negative experiences with gray market products can harm brand loyalty. If a consumer purchases a gray market smartphone that is incompatible with local networks, they may associate the poor experience with the brand rather than the unauthorized seller.

Gray market products are typically sold at lower prices, undercutting authorized sellers and disrupting brand pricing strategies. While some consumers may seek lower prices, they often face risks such as a lack of warranty or the inability to return defective goods.

In industries like automotive parts or pharmaceuticals, gray market imports can raise safety concerns. For example, tires manufactured for different climates may not perform adequately in regions with extreme weather conditions, potentially endangering consumers.

Trademark owners must actively monitor and address gray market activities to protect their brand reputation, maintain pricing strategies, and ensure consumer safety.

The gray market operates in a fine line between lawful commerce and trademark infringement. While consumers may benefit from discounted prices and lower prices, brand protection remains a critical concern. The legal framework provides remedies to brand owners, allowing them to combat unauthorized sales and enforce distribution agreements to sell products exclusively through authorized dealers and authorized retailers. By understanding distribution channels, price discrepancies, and supply chain control, brands can mitigate the effects of gray market sales and meet local regulations.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) allows trademark owners to record their marks with the agency to prevent unauthorized imports. By recording a trademark with CBP, brand owners can request seizures of infringing gray market goods at the border. This proactive measure helps mitigate the influx of unauthorized imports that do not meet U.S. product standards.

Trademark owners can take legal action against unauthorized sellers under the Lanham Act, particularly if the products differ materially from authorized versions. Courts have recognized that selling materially different products under the same mark can create confusion and constitute trademark infringement. In addition to trademark infringement claims, brand owners may also pursue cases under unfair competition laws, alleging deceptive business practices that mislead consumers.

Educating consumers on the risks associated with gray market goods is another critical strategy. By clarifying the differences between authorized and unauthorized sellers, brands can help consumers make informed purchasing decisions. Companies can highlight risks such as lack of warranty coverage, non-compliance with local safety regulations, and absence of manufacturer support.

Implementing product authentication features, such as holographic seals, serial number verification, and digital tracking systems, can also deter gray market sales. These measures help consumers verify the authenticity of their purchases and reinforce the value of buying through authorized channels.

The attorneys at our firm have decades of experience in handling trademark matters. If you have an issue involving gray market goods or other trademark matters, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney