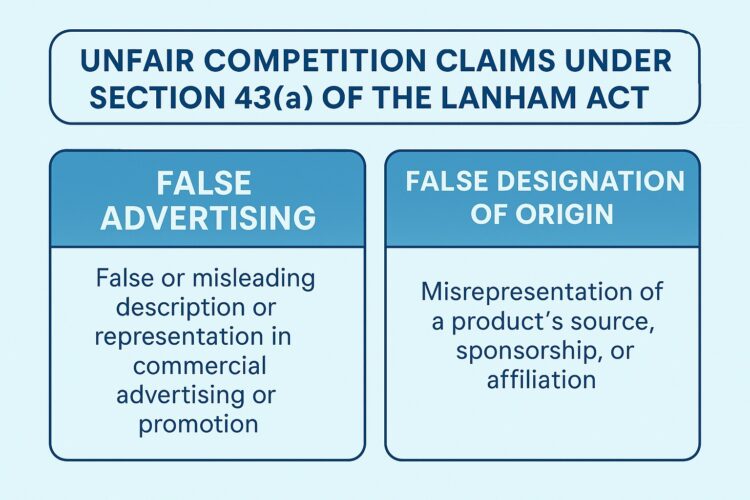

Unfair competition law under 15 U.S.C. § 1125 of the Lanham Act provides a national framework to protect businesses against various deceptive or unfair marketplace practices, including false associations or claims of endorsement, and other false advertising. This law helps maintain fair competition by prohibiting any false or misleading advertising, misrepresentation, or misuse of trademarks that could confuse consumers or harm a competitor’s commercial interests. This article introduces the foundational legal principles of unfair competition under the Lanham Act.

The Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1051 et seq.) is the primary federal statute governing trademark law in the United States. Importantly, 15 U.S.C. § 1125 (Section 43(a)) of the Lanham Act, provides protection for brands, reputations, and marks beyond just trademarks registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). It creates a broad cause of action against anyone who, in interstate commerce, uses “any word, term, name, symbol, or device” or any false or misleading description or representation of fact likely to cause confusion or mistake. In essence, Lanham Act unfair competition covers many forms of deceptive business practices. It prohibits both false designation of origin (misrepresenting a product’s source or sponsorship) and false advertising (misleading claims about goods or services).

This federal protection exists for both registered and unregistered trademarks or trade dress, giving businesses a way to protect their brand identity and reputation in interstate commerce without a registration with the USPTO. In short, Section 43(a) is a powerful legal tool that offers recourse for businesses harmed by deceptive trade practices or fraudulent business acts in the marketplace.

One major facet of Lanham Act unfair competition is the prohibition on false or misleading advertising. Under Section 43(a)(1)(B), a company can be liable if it makes any false or misleading statements of fact in commercial advertising or promotion that misrepresent the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of its own or another’s goods or services. In other words, businesses cannot engage in false advertising or marketing tactics that deceive consumers about a product’s features or origin.

Even literally true statements can violate the Lanham Act if they are presented in a misleading way that confuses or deceives consumers, a false or misleading description can be just as unlawful as an outright falsehood. For example, comparative advertising is common and legal when truthful, but it must be used carefully. In the landmark case U-Haul Int’l v. Jartran, 793 F.2d 1034 (9th Cir. 1986), a competitor’s glossy comparative ads touting better gas mileage and prices were found to be deceptively false, with the Ninth Circuit holding that there is a presumption of deception for literally false, deliberately disseminated comparative ads. The case resulted in a judgment of $40 million in damages plus attorneys’ fees against the advertiser.

The lesson for businesses is clear, false or misleading advertising whether in traditional ads, labels, or commercial promotions creates serious legal risks, including potentially costly legal action by injured competitors. What might seem like aggressive marketing can cross into unlawful deception, so businesses should take care to comply with the legal requirements of the Lanham Act.

The Lanham Act’s unfair competition provisions also cover misuses of trademarks and branding beyond registered marks. Section 43(a)(1)(A) targets “false designation of origin”, which essentially addresses trademark infringement or passing off even when a mark is not registered. It prohibits uses of names, logos, or other marks that are likely to cause confusion or mistake about a product’s origin, sponsorship, or affiliation. In practice, this means a business cannot use a similar mark or trade dress to mislead consumers into thinking its goods or services come from, or are endorsed by, another company. This covers many forms of unfair competition, for example, selling a product with packaging mimicking a competitor’s distinctive design (trade dress infringement), or advertising a service in a way that falsely implies partnership with a well-known brand (false affiliation).

Unlike the Lanham Act’s provisions for registered marks, Section 43(a) gives protection to unregistered trademarks (common law trademarks), allowing companies to sue over trademark violations based on common-law rights and consumer confusion. The key element is consumer confusion: the plaintiff must show that the conduct is likely to confuse or deceive the public about the source or sponsorship of the goods or services. This part of the Lanham Act is closely tied to traditional trademark law principles and ensures that competitors cannot gain an unfair advantage by misleading consumers about who stands behind a product or service. Businesses should note that even without a federal registration from the Trademark Office, they can have recourse under section 43(a) if a rival’s branding causes marketplace confusion and damages their goodwill.

Not every false or harmful statement by a business falls under Lanham Act unfair competition law. The law applies specifically to misrepresentations made in commercial advertising or promotion. Courts have developed criteria to determine if a statement qualifies. Generally, the communication must be commercial speech by a competitor, intended to influence consumers to buy the defendant’s goods or services, and disseminated widely enough to the relevant purchasing public. It should be noted that websites, product pages, and social media campaigns typically disseminate the commercial speech.

This means the Lanham Act is primarily directed to business-to-business disputes over advertising and does not cover mere consumer complaints or editorial content. For instance, a false statement in a competitor’s national ad campaign or product website likely counts as commercial advertising, whereas a one-off comment or a non-commercial opinion piece usually would not. A notable case illustrating this boundary is Edward Lewis Tobinick, MD v. Novella, 848 F.3d 935 (11th Cir. 2017), where a medical doctor sued a blogger for negative statements about his services. The court found the statements were not “commercial advertising or promotion” because the defendant was not in commercial competition with the plaintiff and was not advertising a product.

Thus, the commercial context is crucial. The Lanham Act covers misleading representations in the promotion of goods or services in the marketplace, but it does not turn every harsh review or comment into a federal case. Businesses considering a Lanham Act claim must ensure the offending statements were part of commercial advertising or promotional efforts by a competitor in order to have a valid claim.

The Lanham Act allows “any person who believes that he or she is likely to be damaged” by the unfair competition to sue. In practice, however, not everyone can run to court for false advertising. The plaintiff must have a legitimate commercial interest at stake. The U.S. Supreme Court clarified the standing requirements in Lexmark Int’l, Inc. v. Static Control Components, Inc., 572 U.S. 118 (2014). In that case, the Court set a two-part test, (1) the plaintiff’s injury must fall within the “zone of interests” protected by the Lanham Act (essentially a commercial injury to reputation or sales), and (2) the harm must be proximately caused by the defendant’s false advertising or misrepresentation. This means that typically competitors or others in a commercial relationship can sue, but ordinary consumers generally cannot. As Justice Scalia explained, “to come within the zone of interests in a suit for false advertising under § 1125(a), a plaintiff must allege an injury to a commercial interest in reputation or sales.”

A consumer who is misled into buying a disappointing product might have a grievance, but “he cannot invoke the protection of the Lanham Act.” Similarly, a business that is only indirectly affected might lack standing if the harm is too remote. In short, standing under the Lanham Act is usually limited to those engaged in commerce who suffer competitive or commercial injury from the falsehood. Typically the plaintiff is a business competitor of the defendant. This ensures the Lanham Act is used to protect businesses and fair competition, rather than becoming a general consumer protection statute or defamation law.

A plaintiff that establishes standing must prove the elements of an unfair competition claim under the Lanham Act. Courts generally require the plaintiff to establish all of the following elements:

False or Misleading Statement – The defendant made a false statement of fact, or a statement that is misleading, either literally false, or implicitly deceptive, in a commercial advertisement about its product or another’s product.

Deception of Consumers – The false or misleading statement actually deceived or had the capacity to deceive a substantial segment of its audience.

Materiality – The deception is material, meaning it is likely to influence purchasing decisions.

Interstate Commerce – The misrepresentation affects interstate commerce.

Injury to the Plaintiff – The plaintiff has been or is likely to be injured as a result of the false advertising.

Proving these elements often requires evidence such as advertisements, consumer surveys, and sales data. The burden is on the plaintiff to establish each element. If any element “falls short,” the Lanham Act claim will fail. But if all elements are proven, the defendant will be liable for unfair competition under the statute.

The Lanham Act provides robust remedies once a violation is established. A prevailing plaintiff is typically entitled to injunctive relief and may also recover damages. Injunctive relief is a court order stopping the defendant from continuing the false advertising or infringing use of a mark. In addition, the Lanham Act allows recovery of monetary damages, including the plaintiff’s actual business losses and the defendant’s profits attributable to the wrongful conduct. In the case Romag Fasteners, Inc. v. Fossil, Inc., 590 U.S. 212 (2020), the Supreme Court clarified that willfulness is not strictly required to award profits, but it remains a significant factor. If willfulness or other egregious behavior is shown, courts can award treble damages or attorney’s fees.

These remedies mean that businesses found liable for false advertising or false designation can face serious financial consequences along with being forced to stop the unlawful practices. Conversely, a harmed business has the ability to seek both injunctive and monetary relief to protect its interests.

The key takeaways are that marketing and branding must stay truthful and not create consumer confusion, or you risk liability under the Lanham Act. Conversely, if your business is harmed by a rival’s false claims or misleading promotions, the Lanham Act provides a way to take legal action under federal law in federal court.

By understanding the scope and provisions of Section 43(a), businesses and entrepreneurs can better execute their promotional efforts and protect themselves against unlawful competitive behavior. In sum, Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act helps maintain a level playing field for businesses, guarding against the harms of confusion, falsehood, and unfair competition.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Partnering with Mark Miller at Sierra IP Law is one of the smartest choices I could have made in the world of bringing a new invention to market. He is extremely responsive, knowledgeable, and professional. I could never have conceived of the areas he has advised me on and covered in attempting to write a patent on my own. He and his team have not only insured that my Intellectual Property Rights are well protected, but they have advised and recommended additional protections that I could not have thought of otherwise. I highly recommend Sierra IP Law to anyone looking for a strong and trustworthy legal partner."

Fraser M.

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney