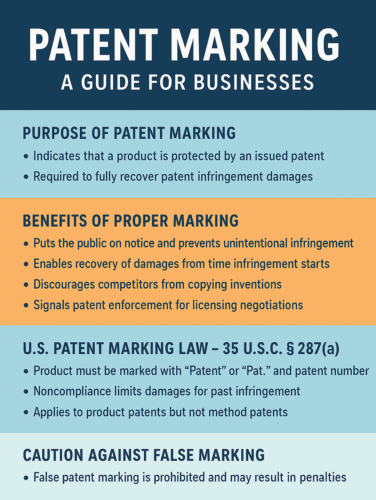

Patent marking is the practice of labeling products with patent information, typically the word “Patent” or “Pat.” followed by a patent number, to notify the public that the product is protected by an issued patent. For business owners new to patent law, understanding patent marking is crucial. Proper marking serves multiple purposes: it provides notice to the public of a product’s patent protection, helps preserve the patent owner’s rights to recover damages for patent infringement, and can deter competitors from copying the patented invention. In the United States, while patent marking is technically optional, it is highly recommended as a best practice for anyone who sells a patented product and may need to enforce their patent rights. This article offers an overview of U.S. patent marking laws, the benefits of marking, how to mark products (including “patent pending” notices and virtual marking), and the pitfalls of false marking.

Patent marking—labeling products with “Patent” (or “Pat.”) and the patent number—alerts the public that an item is protected. While optional under U.S. law (35 U.S.C. § 287), it’s a best practice for businesses selling patented products. Proper marking provides constructive notice, deters competitors, and preserves the patent owner’s right to claim damages for infringement dating back up to six years.

If a product isn’t marked, damages are limited to infringement after actual notice (e.g., a lawsuit or cease-and-desist letter). Marking is especially important for physical products covered by apparatus or design patents. For method-only patents, marking isn’t required, but damages still depend on notifying infringers.

Two marking options exist:

Best practices include marking all units consistently, updating for new or expired patents, requiring licensees and manufacturers to mark, and keeping detailed records.

False marking, claiming “patent pending” without an application, or listing unrelated patents—can lead to legal exposure. Since 2011, penalties require proof of intent to deceive or competitive injury, but honest mistakes (like marking expired patents) are no longer penalized.

In short, marking patented products protects your rights, strengthens enforcement, and helps recover full damages in infringement disputes.

Patent marking exists primarily to give constructive notice of patent rights to the public. By marking patented articles, a patent holder effectively warns others that the product is under patent protection, thereby reducing accidental infringement by those who might unknowingly copy or use the invention. This advance notice can foster an atmosphere of respect for innovation and encourage competitors to design around the patent rather than infringe it. Marking also preserves the patent owner’s ability to claim damages from the earliest possible date of infringement. Under U.S. law, if products are properly marked, the patent owner may recover monetary damages for up to six years of past infringement (the maximum statute of limitations) prior to filing a lawsuit. Without marking, those monetary damages could be severely limited.

By contrast, not marking a patented product can result in lost opportunities to claim patent infringement damages and may invite uninformed parties to infringe, unaware of the patent. In summary, patent marking is a simple step that significantly bolsters a patentee’s patent rights enforcement and patent protection strategy.

The U.S. patent marking statute, 35 U.S.C. § 287(a), establishes the patent marking requirements and the consequences of non-compliance. In essence, the law encourages patentees to mark their products by limiting damages for unmarked products. The statute provides that patentees, and persons making or selling any patented articles, may give notice to the public that the item is patented by marking it accordingly. Specifically, the patent owner should either fix “Patent” (or “Pat.”) and the patent number to the product or, if the article’s size or nature makes physical marking impracticable, affix the information on the packaging in a manner that provides like notice. This marking serves as constructive notice to the public that the article is patented.

Under § 287(a), if a patent owner (or its licensee or manufacturer) fails to mark a patented product, no damages can be recovered for patent infringement that occurred before the infringer was given actual notice of the infringement. In other words, absent marking, the patentee’s damages are limited to infringement occurring after such notice is given to the infringer. Actual notice usually takes the form of a specific communication to the alleged infringer, such as a cease-and-desist letter or the filing of an infringement lawsuit. Importantly, the infringer’s actual knowledge of the patent is not a substitute for the patent holder’s compliance with the marking statute. The law imposes an affirmative duty on the patent holder to mark; even if an infringer knew about the patent, the patent owner still cannot claim damages for earlier infringement without either marking or proving they gave actual notice. As one court explained, the marking notice provisions focus on the patent holder’s conduct, not the infringer’s knowledge.

These marking requirements apply to physical products that are covered by patent claims. Notably, patents on processes or methods are treated differently under the law. For now, the key point is that U.S. patent law offers a carrot-and-stick approach: marking is not mandatory (the statute says a patentee “may give notice” by marking), but failing to mark a patented invention comes with the penalty of forfeiting certain patent rights – specifically, the right to collect past damages prior to notice. Companies seeking to fully enforce their patents and obtain monetary damages for infringement should pay careful attention to these patent marking laws.

You may have seen products labeled “Patent Pending” or “Patent Applied For.” This indicates that a patent application has been filed for the product but a patent has not yet been granted. Marking an item as “patent pending” is permitted during the application process and can serve as a deterrent to competitors by signaling that patent protection is being pursued. However, it is crucial to understand that patent pending status does not confer any enforceable patent rights, one cannot sue for infringement until the patent actually issues. The marking is purely a cautionary notice. Once the patent is granted, the product must be updated to display the patent number (either physically or via virtual marking) to meet the formal marking requirement. Continuing to use “patent pending” after a patent issues, or failing to switch to the actual patent number, can lead to non-compliance with marking regulations and a failure to provide constructive notice.

Equally important is the truthfulness of a patent-pending claim. U.S. law prohibits false claims of patent pending status. According to 35 U.S.C. § 292(a) (false marking statute), it is illegal to mark an article with “patent applied for” or “patent pending” or similar terms when no application is in fact pending, if done with intent to deceive the public. For example, a company should never label a product as “patent pending” if it has not filed a patent application, or if the application was abandoned, as that would constitute false marking. Violations can incur penalties. In practice, as soon as a patent is granted, the marking should be changed from “pending” to “Pat. [Number]”; and if a patent application is abandoned or rejected with no continuing applications, any patent pending labels should be removed to avoid misleading the public. Likewise, if a patent expires, the product should no longer be marked as patented. Continuing to mark an expired patent could be considered misleading.

Traditional physical marking involves affixing patent information directly onto the patented article or its packaging. The marking should include the word “Patent” or the abbreviation “Pat.” followed by the applicable utility patent numbers for the product. For example, a label might read “U.S. Patent No. 10,000,000” or simply “U.S. Pat. 10,000,000.” If multiple patents cover the product, it is common to list each relevant patent number (e.g., “Pat. 9,500,000; 10,000,000”). In the case of design patents, the format “Pat. D123,456” is often used (the “D” indicating a design patent). The goal is to clearly identify which patents cover that product.

Proper marking should be legible and placed where it can be readily seen by the consumer or anyone inspecting the product. The U.S. statute suggests marking the article itself “by fixing thereon” the required information, but it acknowledges that sometimes marking the product directly is not feasible. For instance, if the product is very small, has a surface that cannot easily be stamped or labeled, or if marking it would damage its functionality or aesthetics, then attaching the patent notice to the product’s packaging is acceptable. In those cases, fixing a label with like notice on the package is deemed sufficient as long as the product is sold with that packaging. Manufacturers should ensure the markings are durable (for example, etched, molded, or printed indelibly, if possible) and not easily removable or hidden. If the product is prone to wear or the marking could be worn off, marking the package might be preferred to maintain visibility. What matters is that someone looking at the product or its packaging will receive notice to the public that the item is patented.

Some practical tips for physical marking:

By following these practices for physical marking, companies can ensure effective patent marking, meaning the marking accomplishes its purpose of providing legal notice while also complying with the statute’s specifics.

Virtual patent marking is a modern alternative to stamping patent numbers on products. It was introduced by the America Invents Act (AIA) in 2011 to simplify marking in the digital age. With virtual marking, a product may be marked with an internet address (URL) that leads to a webpage listing the patents associated with that product, instead of listing out patent numbers on the product itself. For example, a label on the product might read: “Patents: www.company.com/patents”. The statute was amended to allow marking by “fixing thereon the word ‘patent’ or ‘pat.’ together with an address of a posting on the Internet” that associates the patented article with its patents. This approach provides flexibility, especially for products covered by many patents or when patents change frequently.

Requirements for a valid virtual marking are:

Virtual marking offers several benefits for companies. It allows quick updates: as soon as a new patent issues or one expires, the webpage can be edited, ensuring you always provide up-to-date information without having to retool a production line. It is also efficient for products that have dozens of patents – instead of trying to list all those numbers on a small device, the single URL covers all of them. Additionally, one URL can cover multiple products and multiple patents in a centralized place. This can save cost and effort, especially for high-tech products or software-related inventions. In fact, software and digital products often rely on virtual marking because there may not be a traditional “label” or physical medium to mark within the software interface itself. For example, software might display an “About” box or a section in settings with patent information, or provide a link to a patents webpage.

To implement virtual marking correctly, companies should create a dedicated patents page on their website, keep it organized (group patents by product or category), and ensure the URL on the product is permanent and easy to type. Using a simple URL or a QR code (with a short URL embedded) can be helpful, though courts have not definitively ruled on QR codes yet. Importantly, document your virtual marking efforts. Maintain dated archives of your patent webpage (even using web archive tools) so you can later prove in court what information was provided at a given time. This kind of evidence can be crucial to show you complied with marking requirements throughout the period of infringement.

In summary, virtual patent marking is a powerful tool that, when done properly, satisfies legal requirements and provides notice just as physical marking does. It’s particularly useful when dealing with many patents or when dealing with intangible products, but it requires diligence to set up and maintain.

Whether using physical or virtual marking (or both), a patent owner should follow best practices to ensure compliance and maximize the benefits of marking:

By adhering to these best practices, businesses can maintain an effective patent marking program. The payoff is twofold: you put the world on notice of your patents (strengthening your legal position and deterring infringement) and you ensure that you preserve your ability to collect full event damages should litigation arise (meaning you won’t leave money on the table due to a technical marking omission).

Not all patents are alike, and the marking rules reflect that. The statute refers to marking “patented articles,” which naturally covers patents that have at least one product or apparatus claim. Here’s how marking requirements break down by patent type:

In summary, apparatus claims (including system and design patents) demand marking of products, whereas method claims do not. If your patent has both, it’s wise to mark any related products to avoid complexity. Always err on the side of providing notice, the effort to mark is usually far less trouble than the complications and limits that arise from not marking.

Failing to comply with the patent marking requirements can significantly impact a patent owner’s enforcement rights. The primary consequence is the limitation on recoverable damages. As discussed, if a patented product was not marked, the patent holder cannot collect damages for infringement that occurred before the infringer received actual notice of the infringement. This can mean a drastic reduction in the compensation the patentee recovers. For example, imagine a competitor has been selling an infringing product for three years before the patent owner discovers it. If the patent owner’s own product wasn’t marked during that time, the owner might only be able to recover damages from the point they notify the infringer (say, via filing the lawsuit) onward, those first three years of infringement could be money lost forever. By contrast, had the product been marked, the patent owner could potentially claim damages for the full three years (and up to three more, since patent law generally allows up to six years of back-damages).

Another consequence is more strategic: not marking might embolden potential infringers. Without a marking, competitors or other parties might not realize your product is patented (no notice to the public), and thus they might inadvertently or even intentionally copy it, thinking it’s safe to do so. While ignorance of a patent is not a defense to infringement, it does remove liability for damages before notice and it also removes the threat of enhanced damages for willfulness in that early period. Essentially, not marking can lead to accidental infringement or surreptitiously intentional infringement by others and leaves you with fewer remedies against them. Marking, on the other hand, can prevent that scenario by making your rights visible from the start.

Courts have also clarified procedural aspects of the marking defense. Once an infringer raises a challenge that a patentee sold unmarked products, the burden can shift to the patent owner to prove compliance. The Federal Circuit in cases like Arctic Cat has outlined that an alleged infringer must first identify specific products that were unmarked and covered by the patent; then the burden shifts to the patentee to show those products were marked or that the patent owner made reasonable efforts to ensure marking. If the patentee cannot show consistent marking or efforts to mark, pre-notice damages will be disallowed.

It’s worth noting that if a patent owner never made or sold any product covered by the patent (for instance, a purely licensing entity or an inventor who hasn’t commercialized the invention), then § 287’s marking provisions do not apply. In such cases, the patentee can still collect damages for up to six years prior to filing suit, because the law only restricts damages when there was a product that could have been marked. Similarly, if infringement is of a method claim only (and no product to mark), the damages can accrue from infringement without marking (subject to actual notice requirements). But these are exceptions to the general rule. Most practicing entities (companies making products) should assume marking is necessary.

In sum, damages awarded for past infringement can be severely affected by a failure to mark. The patent marking requirement is thus not something to overlook. The relatively simple act of marking products can be the difference between recovering a full measure of damages versus losing out on potentially substantial sums of money.

While patent marking is encouraged, false marking is strictly prohibited. False patent marking refers to labeling products in a misleading way regarding patent protection, with intent to deceive the public. There are a few forms this can take, all addressed by 35 U.S.C. § 292:

Originally, false marking was considered a serious offense with steep penalties, historically up to $500 per offense, which courts interpreted as per falsely marked article. This led to a wave of false marking lawsuits around 2009-2011, where enterprising individuals (non-competitors) sued companies for marking products with expired patents or incorrect patent numbers, seeking massive fines. For instance, companies were sued for not removing old patent numbers from products after the patents expired (expired patents technically made those products “unpatented” in the eyes of the law). The Forest Group v. Bon Tool, 590 F.3d 1295 (Fed. Cir. 2009) case confirmed the per-article fine, incentivizing a cottage industry of “marking trolls.” Another notable case, Pequignot v. Solo Cup, 608 F.3d 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2010), involved a manufacturer that kept molding patent numbers into cup lids even after the patents expired, the court held that while the lids were falsely marked (expired patent = unpatented article), the manufacturer avoided penalty by proving it had no intent to deceive: they were trying to save cost on changing molds, not trick the public. This case established that intent to deceive is a required element: honest mistakes or continued use of old markings without deceptive intent are not penalized.

In response to the explosion of opportunistic lawsuits, Congress reformed the false marking law in the AIA of 2011. The changes, reflected in 35 U.S.C. § 292(b)-(c), are:

Even with these changes, false marking is something companies want to avoid. While the threat of random plaintiffs suing has gone away, a competitor could still bring a claim if they can show competitive injury. Moreover, false marking can also draw scrutiny under other laws, such as unfair competition or truth-in-advertising statutes. In a recent Federal Circuit case, Crocs, Inc. v. Effervescent, Inc., 119 F.4th 1 (Fed. Cir. 2024), the court allowed a claim to proceed under the Lanham Act, which governs false advertising, for a company’s marking of products with expired patents. Even though marking expired patents isn’t a § 292 violation anymore, the competitor in that case alleged that doing so was misleading to consumers, essentially a false advertising claim. The Federal Circuit’s decision suggests that blatantly misleading patent markings (e.g. using very old patent numbers to imply a product is patented when it’s not) could be challenged as false advertising, leading to competitive injury liability under the Lanham Act. The best practice is still to ensure your patent markings are truthful and up-to-date to avoid competitive injury claims or reputational harm.

Patent marking may seem like a minor detail in the grand scheme of patent strategy, but it has outsized importance in U.S. patent enforcement. For business owners and attorneys unfamiliar with the process, the key takeaways are: mark your patented products (physically or virtually) to put the world on notice of your rights; doing so preserves your ability to collect full damages if you have to sue for patent infringement. The purpose of marking is to provide public notice (constructive notice) of your patent, which in turn strengthens your hand against infringers and promotes respect for your innovation. Be mindful of the patent marking requirements under 35 U.S.C. § 287, they require marking as a condition to recover certain patent infringement damages. Always ensure your marking is accurate and up-to-date: use “patent pending” only when appropriate, switch to patent numbers once issued, and remove markings when patents expire or no longer apply. Improper marking not only jeopardizes damages but can lead to false marking liability if done with intent to deceive. The law has evolved (especially after the AIA) to curb abuse of false marking claims, yet honesty in marking remains the best policy to avoid any competitive injury claims by rivals.

By understanding and adhering to patent marking laws, patent holders can ensure their innovations are not only protected by patents on paper, but that their patent protection is practical and enforceable in the market. If you have questions about patent enforcement or other intellectual property matters, please contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney