When a competitor registers a trademark that interferes with your brand or violates your rights, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) provides a mechanism to challenge it: the petition to cancel. A cancellation proceeding is a process administered by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) of the USPTO that allows you to contest a trademark registration if you have better rights in the mark or a highly similar mark, or if the registration was wrongfully issued. Trademark cancellation proceedings are useful tools for protecting your trademark rights from third party competition and eliminating invalid registrations.

In this article we provide an overview of the petition for cancellation process, the relevant trademark law, and strategic considerations in pursuing a trademark cancellation.

A petition to cancel is an administrative legal filing submitted to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB), requesting the invalidation of an existing trademark registration. This administrative action is available for marks listed on either the Principal Register or the Supplemental Register maintained by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Cancellation proceedings are pursued after registration, making them an essential post-registration mechanism. Cancellation actions differ from trademark opposition proceedings, which are initiated before a trademark registers.

Cancellation proceedings resemble traditional litigation in federal court, though they are handled entirely within the administrative framework of the TTAB. The party filing the cancellation (the petitioner) assumes the role of the plaintiff, while the registrant (the respondent) is considered the defendant. The process begins with the filing of a petition for cancellation, which includes the factual and legal grounds upon which cancellation is sought. These proceedings follow structured timelines for pleadings, discovery, submission of evidence, and trial briefs, culminating in a decision by a panel of administrative trademark judges.

The TTAB has exclusive jurisdiction over the registration status of trademarks. It cannot grant monetary damages or injunctive relief; its power is limited to determining whether a mark should remain registered. Common grounds for filing a petition include nonuse, abandonment, fraud, likelihood of confusion, and genericness. See TBMP § 301.01; 37 C.F.R. § 2.111(a).

Under Lanham Act § 14 (15 U.S.C. § 1064), “[a]ny person who believes that he is or will be damaged” by a registered trademark may initiate a petition to cancel. This broad statutory language opens the door to a wide range of parties, including businesses, individuals, and organizations, who can show that they possess a legitimate stake in the outcome of the cancellation action.

However, mere dissatisfaction or generalized concern is not enough. The TTAB and the federal courts have interpreted the statute to require that a petitioner demonstrate a real interest in the proceeding and a reasonable basis for the belief that damage will occur if the registration remains in effect. A "real interest" generally means that the petitioner has a direct commercial stake, such as selling similar goods or services under a potentially conflicting mark, or being blocked by the registered mark during examination of their own trademark application.

Courts have further clarified that a petitioner must hold a reasonable and good faith belief that they are likely to be harmed by the registration and that the harm is not merely hypothetical. This standard was articulated in Australian Therapeutic Supplies PTY. Ltd. v. Naked TM, LLC, 965 F.3d 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2020), where the Federal Circuit emphasized the need for a petitioner to have a legitimate commercial interest.

In practice, petitioners often include prior users of a mark, owners of similar trademarks, or businesses facing legal or market barriers due to the registered mark. Legal counsel can help establish standing based on available facts and strategic objectives.

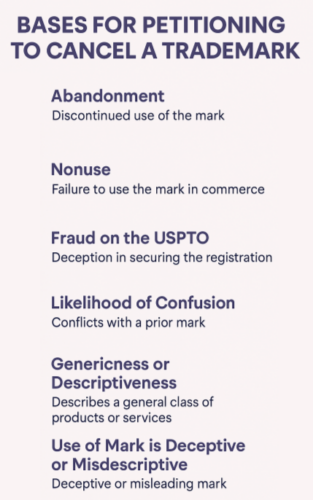

A petition to cancel a trademark registration must be based on valid legal grounds recognized under the Lanham Act and TTAB precedent. These grounds fall into substantive and procedural categories and are codified primarily in 15 U.S.C. § 1064 and related sections. The most commonly asserted bases include the following:

A mark is deemed abandoned when its use has been discontinued with no intent to resume. Under the Trademark Act, nonuse for three consecutive years constitutes prima facie evidence of abandonment. 15 U.S.C. § 1064(3). Petitioners must show either a complete cessation of use or intent not to resume use.

If a registrant never used the mark in commerce as required prior to registration, the registration is subject to cancellation. This is particularly relevant for intent-to-use applications that matured to registration without bona fide use. The expedited cancellation pilot program specifically targets such nonuse claims to streamline removal of unused marks from the register.

Fraud occurs when a registrant knowingly makes a false, material representation of fact with the intent to deceive the USPTO during the prosecution or maintenance of a trademark registration. To prevail on a fraud claim, the petitioner must demonstrate that the registrant acted with scienter and that the misrepresentation was material to the USPTO’s decision to approve or maintain the registration. In Great Concepts, LLC v. Chutter, Inc., 84 F.4th 1014 (Fed. Cir. 2023), the Federal Circuit held that the TTAB lacks authority to cancel a registration based solely on false statements made in a declaration of incontestability under Section 15 of the Lanham Act, because such statements are not material to the continued validity of the underlying registration itself. This demonstrates the high bar required for a successful fraud claim.

A registration may be cancelled if it is likely to cause confusion with a previously used or registered mark. The TTAB evaluates this under the DuPont factors, considering the similarity of marks, goods/services, and trade channels. In order to successfully pursue a cancellation proceeding on this basis, the petitioner must have trademark rights that are earlier than the trademark registration date and earlier than the registrant's first use of the mark in commerce.

A generic term cannot function as a trademark. Descriptive marks may also be cancelled if they lack acquired distinctiveness. Petitioners must show that consumers perceive the term as merely describing the goods/services rather than indicating source.

Owners of famous marks may assert dilution by blurring or tarnishment. Unlike confusion-based claims, dilution does not require competing goods or services, only that the junior mark weakens or harms the reputation of the famous mark.

A mark may be cancelled if it is deceptively misdescriptive or outright deceptive. This includes marks that misrepresent the geographic origin, quality, or nature of goods/services in a way likely to deceive consumers.

These statutory grounds are not exhaustive, but they represent the most frequently asserted bases in trademark cancellation proceedings. For more detail, see Chapter 300 of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Manual of Procedure (TBMP) and the TTAB's developing jurisprudence, particularly in light of evolving standards on fraud and administrative adjudication.

While the Lanham Act provides robust tools for challenging trademark registrations, petitioners must be mindful of critical time limitations imposed by 15 U.S.C. § 1064. In general, certain grounds for cancellation must be asserted within five years from the date the registration issued. The most common example is a claim based on likelihood of confusion with a prior mark, which is time-barred after five years unless specific exceptions apply.

However, not all cancellation claims are subject to the five-year limit. The statute expressly allows some grounds to be raised at any time, including claims of fraud, abandonment, genericness, and functionality. These exceptions recognize that some flaws go to the heart of a mark’s validity or its ongoing use in commerce.

Importantly, the five-year bar applies only to marks on the Principal Register. Marks on the Supplemental Register, which lack inherent distinctiveness, remain subject to cancellation on any ground at any time. Additionally, if the registration was obtained through fraud, or if the mark has become generic or abandoned after registration, the five-year limitation does not apply.

Failure to observe these time constraints can result in dismissal of the petition to cancel, even if the substantive claims are otherwise strong. As such, assessing the trademark registration date and understanding which grounds survive the five-year mark is essential to pursuing a timely and effective cancellation action.

To initiate a trademark cancellation proceeding, a petitioner must file a petition to cancel through the Electronic System for Trademark Trials and Appeals (ESTTA), the USPTO’s official online filing platform for TTAB matters. The process begins by selecting the appropriate ESTTA form, inputting required information about the registered mark (e.g., the trademark, the goods or services, the registration number, etc.), the grounds for cancellation, and the petitioner’s standing to bring the action. The petition must clearly set forth the factual and legal basis for cancellation, akin to a complaint in a civil lawsuit. A filing fee is required for each class of goods or services in the challenged registration. As of 2024, the required fee is $600 per class, though this amount may be updated by the USPTO periodically.

Once the cancellation petition is filed, the TTAB issues a formal notice of institution, which sets forth deadlines for the respondent to file an answer and provides a schedule for discovery, disclosures, and trial periods. If the ESTTA system is unavailable due to technical problems or if extraordinary circumstances exist, a petitioner may file on paper, but only with prior approval and a petition to the Director under 37 C.F.R. § 2.146.

TTAB proceedings are adversarial in nature and closely follow the procedures used in federal civil litigation. Discovery in a cancellation proceeding is governed by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP), as supplemented by TTAB-specific rules found in the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Manual of Procedure (TBMP). Once the respondent files an answer, the parties are required to conduct a discovery conference, during which they must discuss the nature of the claims and defenses, possibilities for settlement, anticipated discovery needs, and issues related to the preservation and disclosure of electronically stored information (ESI).

Following the conference, parties must serve initial disclosures, which include basic identifying information about potential witnesses and relevant documents. Discovery tools available to each party include interrogatories, requests for production of documents, requests for admission, and depositions. These tools are used to develop evidence and clarify claims and defenses before trial. The discovery period typically lasts six months, unless extended by stipulation or Board order. Effective use of discovery can shape the trajectory of the case and position the petitioner or respondent for a favorable outcome at trial. See TBMP Chapter 400.

Following the close of discovery, the TTAB schedules a series of testimony periods during which the parties present their evidence (e.g., USPTO records, petitioner trademark use records, deposition testimony, etc.), akin to the trial phase in a civil lawsuit. These periods are strictly regimented and controlled by the Trademark Rules of Practice, particularly 37 C.F.R. § 2.121, and detailed in TBMP Chapter 700.

The plaintiff/petitioner is assigned the first 30-day testimony period to present its legal case, followed by a 30-day testimony period for the defendant/respondent to rebut the petitioner’s claims and present any affirmative defenses or counterclaims. A final 15-day period is reserved for the petitioner to present rebuttal evidence.

Evidence may be submitted through oral testimony (depositions), or in written form via affidavits or declarations, provided they comply with the strict requirements of 37 C.F.R. §§ 2.123, 2.124, and 2.125. Parties must also serve pretrial disclosures identifying witnesses and documents no later than 15 days before the opening of each testimony period. Failure to observe these deadlines can result in exclusion of evidence.

The testimony period is a critical phase where parties “try” their case on the written record. There is no live courtroom trial; instead, the TTAB evaluates the case based solely on the submitted evidence and written briefs.

After the close of the testimony periods, each party is permitted to file a trial brief summarizing the relevant facts, legal arguments, and supporting authority. These briefs are critical because they serve as the parties’ final opportunity to persuade the TTAB to rule in their favor. The brief must cite to the record created during the testimony period and should avoid introducing any new evidence, which is not permitted at this stage.

Typically, the plaintiff/petitioner files an opening brief, followed by the defendant/respondent’s answering brief. The petitioner may then file a reply brief. Briefs are filed electronically through ESTTA, and specific formatting and page limits apply under 37 C.F.R. § 2.128.

Either party may request an oral hearing, which gives counsel the chance to present a live summary of their arguments before a panel of TTAB administrative judges. Although not required, oral argument can be strategically valuable in complex cases or those involving nuanced legal questions.

After reviewing the evidence, trial briefs, and (if requested) oral argument, the TTAB will issue a final written decision. This decision includes findings of fact, legal analysis, and the Board’s ruling on whether the trademark registration will be cancelled or maintained. The TTAB’s decision becomes final unless appealed within the statutory period.

Under 15 U.S.C. § 1071, the losing party has two primary options for appeal. First, they may file an appeal directly to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which will review the TTAB’s decision on the existing administrative record. Alternatively, the party may initiate a civil action in a U.S. District Court, which allows for de novo review and the opportunity to introduce new evidence.

Each appeal route has strategic implications. The Federal Circuit provides a faster and narrower review, while district court litigation can accommodate evidentiary expansion but involves greater cost and complexity.

The USPTO’s Expedited Cancellation Pilot Program was developed to efficiently address straightforward nonuse claims, where the registrant is alleged never to have used the mark in commerce. This program streamlines the standard TTAB process by reducing procedural complexity, limiting discovery to essential disclosures, and accelerating the litigation timeline. It is ideal for clear-cut cases involving abandonment or lack of use, offering a cost-effective route to remove deadwood from the Principal Register.

Before initiating a cancellation action, it is important to carefully assess the factual and legal basis for the claim. Begin by evaluating the registrant’s actual use of the mark in commerce. Search for verifiable evidence of current or prior use, or a lack thereof, particularly if alleging nonuse or abandonment. Consider factors such as advertising, packaging, online presence, and sales activity.

Simultaneously, you should document your own prior rights, including use in commerce, dates of first use, and geographic scope. Collect business records, marketing materials, domain registrations, and any relevant registrations or applications to support your position.

Not every trademark conflict requires formal litigation. You may consider alternative approaches, such as sending a cease-and-desist letter, initiating settlement discussions, or negotiating a coexistence agreement. These strategies can resolve disputes more quickly and at a lower cost.

It is also important to assess whether the challenged registration is blocking your trademark application. If so, successful cancellation may clear the path to your own registration.

Finally, engaging an experienced trademark attorney is critical. TTAB proceedings follow strict procedural rules and evidentiary standards. Missing deadlines, failing to present evidence properly, or misunderstanding standing and grounds for cancellation can result in dismissal or permanent loss of rights.

Conclusion

Filing a petition for cancellation is a powerful way for trademark owners to protect their brand. However, it is a serious undertaking and should only be pursued after careful consideration. A cancellation proceeding is a complex adversarial proceeding requiring careful strategy. If you need assistance with a trademark dispute, a trademark registration, or other trademark matter, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney