Trademark counterfeiting is the unauthorized use of a counterfeit mark, essentially unauthorized use of a business's exact trademark on goods or services not provided by the company, with the intent to deceive consumers into believing they are buying genuine products. This form of trademark infringement is a growing problem in global commerce, harming legitimate businesses and consumers alike. Counterfeit goods are often sold at low prices and can be dangerous or substandard, damaging a company's reputation and funding organized crime or even child labor operations. This article provides an overview of U.S. laws against trademark counterfeiting, explains the differences between counterfeiting and ordinary infringement, and outlines the civil remedies and criminal penalties that trademark owners and authorities can pursue.

Under U.S. law, a “counterfeit” is defined as “a spurious mark which is identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from, a registered mark.” In simpler terms, a counterfeit mark is a fake trademark that is nearly identical to a real, registered trademark or service mark owned by someone else. The counterfeit mark is typically used on the same goods or services for which the genuine mark is registered, in order to deceive consumers. For example, applying a fake Louis Vuitton logo to a purse and selling it as a Louis Vuitton product is trademark counterfeiting. The Lanham Act (federal trademark law) makes it clear that counterfeiting applies only to marks registered on the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Principal Register. If a mark is not registered, the unauthorized use may be trademark infringement or unfair competition, but not trademark counterfeiting under the statutory definition.

To qualify as a counterfeit, the fake mark must be used in connection with the sale, offer for sale, or distribution of goods or services. The goods or services bearing the counterfeit mark also must be identical or virtually identical to the genuine article. Using a famous mark on completely different goods might be infringement, but it wouldn’t meet the definition of a counterfeit trademark if the product is not the same or substantially indistinguishable from the real one. The goal of a counterfeiter is to make a product that so closely imitates the genuine product, including copying the packaging and trademarks, that consumers will be deceived or confused into thinking they are buying the real thing. In trademark counterfeiting cases, unlike ordinary infringement, courts often presume a likelihood of confusion because the counterfeit mark is identical to the real mark by design.

It is important for business owners and entrepreneurs to understand the distinction between standard trademark infringement and the more egregious act of trademark counterfeiting. Trademark infringement can involve any unauthorized use of a mark that is likely to cause confusion about the source or sponsorship of goods or services. In typical infringement cases, courts examine factors such as similarity of the marks and evidence of actual confusion. Counterfeiting, by contrast, is a subset of infringement where the defendant’s mark is not just similar, but a virtually exact copy of the genuine mark, used on the same type of product with an intent to pass off the goods as genuine. Because a counterfeit mark is intended to be indistinguishable from the real mark, proof of consumer confusion is almost inherent. The law assumes that a customer buying a “Rolex” watch with Rolex’s exact trademarks will be confused, so lengthy analysis of confusion factors is usually unnecessary.

In essence, all counterfeits infringe, but not all infringements are counterfeits. For example, if an unrelated company uses a similar name that leads to confusion, it’s infringement; but if they use your exact registered trademark on knockoff goods, that is counterfeiting. This distinction matters because counterfeit trademark offenses carry stronger remedies and penalties than ordinary infringement. The Lanham Act was amended in 1984 to arm trademark owners with these stronger tools when dealing with intentional use of counterfeit marks in commerce. In civil cases, the law mandates or encourages higher damages and attorney fee awards for willful counterfeiting, and in criminal law, counterfeiting is explicitly a crime, whereas ordinary infringement is generally a civil matter.

Congress addressed the growing problem of trademark counterfeiting with the Trademark Counterfeiting Act of 1984, which amended federal law to provide both civil remedies and criminal penalties for counterfeiting. Under the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1114), a trademark owner can file a civil lawsuit for trademark counterfeiting. To succeed, the owner must prove that the defendant intentionally used a counterfeit of the plaintiff’s mark that is registered on the USPTO Principal Register, in connection with the sale or distribution of goods or services, and that such use is likely to deceive or cause confusion among the public.

The 1984 Act also added powerful new provisions to the Lanham Act. Courts were given authority to issue ex parte seizure orders, meaning the trademark owner can, without prior notice to the defendant, get a court order to seize counterfeit materials (the fake goods, labels, packaging, etc.) to prevent their concealment or transfer. This extraordinary remedy is available in civil cases involving counterfeits because counterfeiters often conceal or quickly dispose of fake goods if warned in advance. To get such an order, the trademark owner must satisfy strict requirements to show that an immediate seizure is necessary and all statutory conditions are met: proof of location of goods, risk of destruction, likelihood of success on the merits, and irreparable harm would occur to plaintiff that outweighs the harm to the defendant.

Under the Lanham Act’s civil provisions, trademark owners can seek injunctive relief (court orders to stop the unauthorized use of the mark) and monetary damages. Civil remedies for counterfeiting are notably harsher than for normal infringement. The law provides for mandatory treble damages and an award of attorney’s fees for intentional counterfeiting in many cases. 15 U.S.C. § 1117(b) requires courts to award three times the profits or damages, plus reasonable attorney fees, if the court finds the defendant’s use of the counterfeit mark was willful, unless the defendant can prove “extenuating circumstances”. Extenuating circumstances is a narrow exception meant for truly extraordinary situations, such as an infringer’s extreme hardship. By contrast, ordinary infringement remedies under §1117(a) are subject to the court’s discretion and generally don’t mandate trebling or fees.

Additionally, a trademark owner may elect statutory damages specifically for counterfeiting instead of proving actual damages. The Lanham Act allows statutory damages ranging from $1,000 up to $200,000 per counterfeit mark, and up to $2,000,000 per mark if the infringement was willful. These high statutory damages provide a powerful deterrent and relieve the plaintiff from the burden of proving actual losses in cases where counterfeiters often hide or have no records of profits.

It is worth noting that a defendant cannot escape liability simply by claiming ignorance if the circumstances indicate deliberate avoidance of the truth. Courts have held that “willful blindness” to the counterfeit nature of goods is sufficient to satisfy the knowledge requirement. See Louis Vuitton S.A. v. Lee, 875 F.2d 584 (7th Cir. 1989) discussed below. A defendant who knew or should have known that they were dealing in counterfeits can be found liable for counterfeiting.

Trademark counterfeiting is not only a civil matter, it is also a crime under U.S. federal law. The Trafficking in Counterfeit Goods statute (18 U.S.C. § 2320) makes it a federal offense to intentionally traffic in goods or services while knowingly using a counterfeit mark on or in connection with those goods or services. In a criminal prosecution, the government must prove four elements: (1) the defendant trafficked or attempted to traffic in goods or services, (2) the trafficking was intentional, (3) the defendant used a counterfeit mark on or in connection with those goods or services, and (4) the defendant knew the mark was counterfeit. In other words, selling or distributing fake branded products with knowledge that the marks are counterfeit is a crime. The law also explicitly includes those who traffic in counterfeit labels or packaging: e.g., selling fake trademark labels separately with intent to attach them to products.

The maximum penalty under federal law for a first-time trademark counterfeiting conviction is up to 10 years in prison and up to $2,000,000 fine for an individual, or $5,000,000 for a company. For repeat offenders, penalties double to 20 years and $5,000,000, and up to $15,000,000 for companies. These severe penalties reflect that Congress views counterfeiting as a serious crime often linked to fraud and organized crime. Indeed, proceeds from counterfeit goods have been connected to criminal organizations, and counterfeit operations have involved exploitation, such as forced or child labor in manufacturing. Certain cases involving counterfeit goods that pose a threat to health or safety, like fake pharmaceuticals or automobile parts are punished particularly harshly, often receiving the upper end of penalties.

In addition to federal law, California explicitly criminalizes trademark counterfeiting. Under California Penal Code § 350, it is illegal to willfully manufacture, intentionally sell, or knowingly possess for sale any goods bearing a “counterfeit mark”. The law defines a “counterfeit mark” similarly to the Lanham Act: an unauthorized mark that is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark registered either federally (with the USPTO) or with the California Secretary of State. Notably, a violation requires a knowing state of mind: California interprets “knowingly” to mean the person knew or had reason to believe the mark was counterfeit.

California’s penalties for trademark counterfeiting depend on the scale of the operation and the value of the counterfeit goods. Small-scale offenses (involving fewer than 1,000 counterfeit items with a total retail value under $950) are typically charged as misdemeanors. But larger operations exceeding those thresholds can be prosecuted as felonies, with penalties including up to three years in state prison and very heavy fines. This graduated penalty scheme ensures that a small vendor selling a handful of fake handbags faces far lighter punishment than an organized ring trafficking in high-value counterfeit products. As in other states, California business owners should be aware that counterfeit activities can lead to state criminal charges, not just federal prosecution.

Other states have stricter penalties Texas law explicitly criminalizes trademark counterfeiting (Texas Penal Code § 32.23). Small-scale offenses are misdemeanors (goods are worth less than $100) while larger operations are felonies, up to a first-degree felony if the goods are worth $300,000 or more. A first-degree felony can mean 5 to 99 years in prison.

When a business discovers that counterfeit products bearing its trademarks are in the marketplace, it has several civil remedies at its disposal under the Lanham Act. First and foremost, the trademark owner can seek an injunction, or court order to immediately stop the counterfeit sales. Courts can grant temporary restraining orders and preliminary injunctions early in the case to halt the trafficking of fake goods. In fact, because counterfeiters often vanish or hide assets, trademark owners frequently proceed ex parte, without advance notice to the defendant to obtain a seizure order and freeze the defendant’s assets. An ex parte seizure order under 15 U.S.C. § 1116(d) allows U.S. Marshals to seize the counterfeit goods, inventory, and business records from the infringer’s premises, preventing the distribution of the fake goods and preserving evidence. This remedy is available only in counterfeiting cases, and the plaintiff must meet strict criteria to justify it, such as showing that an injunction alone is inadequate and the defendant would likely destroy or conceal the goods if given notice.

In the civil lawsuit, the trademark owner can also demand monetary relief. The Lanham Act gives several options: the plaintiff can seek actual damages (including the profits the counterfeiter made and the harm to the trademark owner’s sales and goodwill) or elect statutory damages as discussed earlier. Often, statutory damages are chosen in counterfeiting cases because calculating actual losses can be difficult when counterfeiters operate in the shadows. Additionally, if the counterfeiter’s conduct was willful, the court must award enhanced damages, which are typically treble the amount of actual damages or profits. Even if a counterfeiter claims they didn’t realize the goods were fake, that is not a defense to liability. However, a truly innocent infringer (i.e., did not have reason to know the goods were counterfeit) might avoid the willfulness finding, but they would still at least owe the trademark owner’s lost profits or damages for the infringement.

The court can also order the destruction of the counterfeit goods once the case is concluded, so they don’t re-enter the market. Under 15 U.S.C. § 1118, any counterfeit items and related materials (labels, packaging, etc.) in the defendant’s possession can be seized and destroyed by court order. This ensures that counterfeit goods are permanently removed from commerce. Furthermore, trademark owners might recover investigative costs and can seek to have the defendant pay for corrective advertising to restore the company’s reputation if it was tarnished by shoddy counterfeit products.

To appreciate how these laws work in practice, it’s helpful to consider a few examples. In Louis Vuitton S.A. v. Lee, 875 F.2d 584 (7th Cir. 1989), Louis Vuitton sued a retailer who sold fake Louis Vuitton and Gucci handbags. The court found the seller liable for counterfeiting and emphasized that willful blindness to the authenticity of the products did not excuse the infringement. Mrs. Lee had purchased designer-branded bags from an itinerant street peddler at extremely low prices, and the bags were of obviously poor quality (e.g., misaligned patterns and cheap linings). The court reasoned that any reasonable seller would suspect such “deals” as fakes, and it held that “willful blindness is knowledge enough” to meet the requirement that the defendant knew the mark was counterfeit. The result was that the defendants were ordered to pay trebled profits to Louis Vuitton and the plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees, as mandated by the anti-counterfeiting provisions. The case demonstrates that even retailers or middlemen can be held accountable if they know or should know they are dealing in counterfeit goods.

Another noteworthy example is the federal prosecution in United States v. Lundgren, No. 17-12466 (11th Cir. Apr. 11, 2018), where a distributor was criminally convicted for trafficking in counterfeit Microsoft software. In that case, evidence showed the defendant knowingly sold CDs with unauthorized Microsoft trademarks. He received a prison sentence under 18 U.S.C. § 2320, illustrating that knowingly trafficking in fakes is a serious felony. Mr. Lundgren was sentenced to 15 months in prison and $700,000 in restitution was ordered.

Civil courts have also imposed huge statutory damage awards in counterfeiting cases to deter counterfeiters. In Omega SA v. 375 Canal, LLC, 984 F.3d 244 (2d Cir. 2021), the defendant was found liable for $1.1 million for allowing the sale of counterfeit Omega watches on its property. 375 Canal leased its property with knowledge that the tenant was engaged in the sale of counterfeit goods.

It should be noted that federal courts will use the value of genuine goods to restrict statutory damages where appropriate. For example, in Coach, Inc. v. Treasure Box, Inc., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 28713, Coach was seeking $100,000 in statutory damages (half the maximum amount) per counterfeit mark, of which there were 15. The court found that the infringement was brief and trivial, amounting to little in the way of damage or profits. The court ultimately awarded $3,000/mark and attorney's fees of $14,780. This demonstrated that courts are willing to consider the actual impact of the counterfeit use in determining statutory damages. However, the penalty for even small or trivial counterfeiting was significant, amounting to $59,480.

Trademark counterfeiting is far from a victimless crime. Trademark owners suffer lost sales and erosion of brand value when counterfeiters flood the market with cheap imitations. It’s estimated that U.S. businesses lose billions of dollars annually due to counterfeit sales. Beyond the direct profits stolen, there is significant damage to a company’s goodwill and brand reputation. Consumers who unwittingly buy fake products and receive inferior or dangerous items may associate that poor quality with the real brand. As one intellectual property litigator noted, “the damage to a company's reputation that arises from consumers who attribute a faulty or low-quality counterfeit product to the trademark owner itself can be severe.” If a fake phone charger catches fire, for example, consumers might blame the genuine manufacturer, not realizing their charger was an imitation. This loss of trust can be devastating over time.

Consumers are also put at risk by counterfeits. Many counterfeit goods, from electronics to pharmaceuticals to cosmetic items, are produced without regard to safety standards, leading to hazards such as toxic ingredients or malfunctioning parts. Counterfeit luxury goods, while perhaps not life-threatening, still cheat consumers out of the quality they expected and support illicit enterprises. On a societal level, money from fake products may fund international organized crime, and the manufacturing of counterfeits overseas has been tied to sweatshop conditions, child labor, and even financing of other illegal activities. The International Anti-Counterfeiting Coalition (IACC) and other organizations lobby and work with law enforcement globally to combat these issues.

The proliferation of online commerce has made counterfeiting easier and enforcement harder. Online counterfeiters and infringers can set up transient websites or sell through online marketplaces, using anonymous accounts and false supply chain information to avoid detection. They often ship products directly to consumers, sometimes declaring them as “gifts” or using innocuous labels to slip past Customs. Enforcement agencies like U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) are actively seizing counterfeit imports. Nearly 90% of counterfeits seized at U.S. borders originate from China or Hong Kong. Still, the sheer volume of small packages in e-commerce poses a challenge, as counterfeiters conceal themselves among legitimate sellers.

For all these reasons, U.S. law treats trademark counterfeiting as a serious offense, with stronger remedies and punishments intended to protect both businesses and consumers. Legitimate businesses can also take proactive steps to guard their brands, as discussed next.

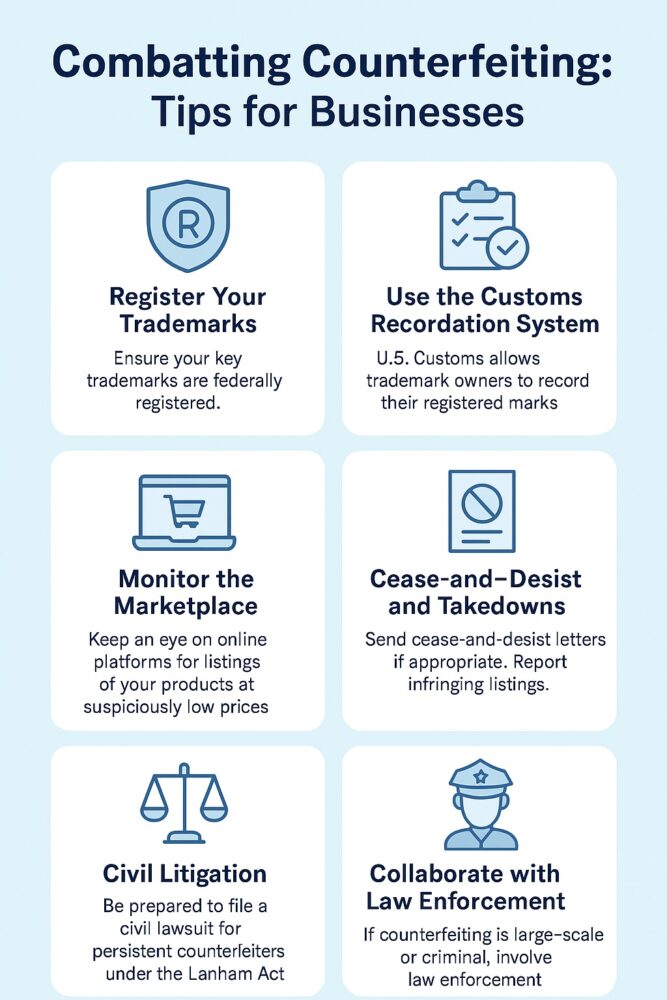

Every business with a valuable brand should be proactive about anti-counterfeiting efforts. Here are some strategies and remedies companies can use to prevent and respond to trademark counterfeiting:

By taking these steps, legitimate businesses can reduce the harm of counterfeiting and strengthen their position if legal action becomes necessary. While pursuing counterfeiters can be costly and complex, the civil and criminal remedies available – from damages and seizures to fines and imprisonment – provide a strong framework to combat this illegal activity and protect both the brand and consumers.

Trademark counterfeiting is a serious legal and economic issue, but U.S. law provides robust tools for trademark owners to protect their brands and for prosecutors to penalize offenders. Unlike ordinary trademark disputes, counterfeiting involves the intentional, fraudulent use of somebody else’s mark on identical goods, essentially a form of fraud on the public. The Lanham Act and the Trademark Counterfeiting Act (with its amendments to criminal law) establish that those who engage in this illicit trade may face everything from multi-million dollar statutory damages and trebled liability in civil cases to felony convictions with prison time in criminal cases.

If you have a trademark infringement or counterfeiting situation, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney