The trademark opposition process is a legal procedure conducted at the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) that allows a third party to challenge a pending trademark application before it becomes registered. The TTAB is an administrative tribunal within the USPTO. It is a useful tool for businesses to understand how to oppose a trademark application. A trademark opposition is essentially a mini-lawsuit focused on whether a trademark application should be refused registration. The procedure is not trademark litigation and does not address infringement, only the right to register the mark. Oppositions are most often filed in order to prevent registration of mark that is highly similar to the opposing party's trademark or brand. It is a tool to protect the opposer's rights to its mark and branding from a newcomer with similar branding plans.

This article provides an overview of the trademark opposition proceeding, from the mark’s publication to final decision, including timelines and common issues.

A trademark opposition is a formal challenge to the registration of a trademark. After an examining attorney at the trademark office reviews a trademark application and approves it, the application is published in the USPTO’s Official Gazette for opposition. Publication is essentially a public notice that the USPTO intends to register the mark, unless an interested party files an opposition. There is a 30-day opposition period, and the opposition or a request for extension to file an opposition must be filed prior to the expiration of the opposition period. Any person who believes they would be damaged by the registration of the proposed trademark may file a Notice of Opposition within the allowed time. See 15 U.S.C. § 1063. In simple terms, if you own prior trademark rights or have another legitimate interest and you think a pending trademark registration will harm your business (for example, by causing consumer confusion with your brand), you can initiate an opposition.

Oppositions are filed with the TTAB, which acts as an appeal board within the USPTO to decide these disputes. The TTAB’s proceedings are adversarial, involving two parties: the opposer (the party challenging the mark) and the trademark applicant whose mark is being opposed. A trademark opposition proceeding shares some features with federal litigation, including pleadings, discovery, and trial phases. However, unlike litigation, it is generally handled through written submissions and evidence rather than live court hearings. The goal of an opposition is to determine whether the applied-for trademark should be refused registration on the Principal Register due to legal problems with the mark or the application.

Not just anyone can oppose a trademark; the opposer must have a real interest in the case. The law states that “[a]ny person who believes that he would be damaged by the registration of a mark upon the principal register… may, upon payment of the prescribed fee, file an opposition”. In practice, an opposer must show they are not a mere intermeddler: they need a legitimate stake in the outcome (often called “standing”). The TTAB and courts interpret this to mean the opposer must be within the “zone of interests” protected by the Trademark Act and have a reasonable belief that they will be harmed by the mark’s registration. For example, a company that owns an existing trademark can claim damage if a proposed mark is similar enough to cause market confusion, or an individual might oppose a mark that falsely suggests a connection to their identity or brand.

Importantly, the opposer does not need to prove actual damage; a belief in likely harm (such as loss of distinctiveness or reputation) is enough to initiate the case. The Federal Circuit has confirmed that a reasonable basis for his belief of damage is enough. A direct and personal stake in the outcome must be present. For instance, in Ritchie v. Simpson, 170 F.3d 1092 (Fed. Cir. 1999), the court allowed a consumer to oppose O.J. Simpson’s trademark applications, finding the consumer had a reasonable basis to believe the marks (related to Simpson) would damage him, thus meeting the standing requirement. In Ritchie v. Simpson, William B. Ritchie opposed registration of marks including O.J. SIMPSON on the grounds they were scandalous under § 2(a) or primarily merely a surname under § 2(e)(4). The TTAB dismissed his opposition for lack of standing, calling him a “mere intermeddler.” The Federal Circuit reversed, holding Ritchie met the statutory standard: he had a real interest in the proceedings and a reasonable basis to believe he’d be damaged by registration. That recognition affirmed broad statutory standing under 15 U.S.C. § 1063.

In summary, if you are a business owner or individual with prior rights or a legitimate interest that might be harmed by a mark’s registration, you have standing to file a trademark opposition.

Having standing is only the first step. The opposer must also plead one or more valid grounds for opposition. The Trademark Act provides various statutory grounds on which a trademark’s registration can be opposed. Below are some of the common grounds used in opposition proceedings. Each corresponds to a provision of the Lanham Act and has been recognized in TTAB cases:

In the Notice of Opposition, the opposer must clearly state the ground(s) being asserted and the factual basis for each ground, so the applicant is on notice of the claims. If even one ground is proven by the end of the case, the opposition will succeed and the trademark will not register.

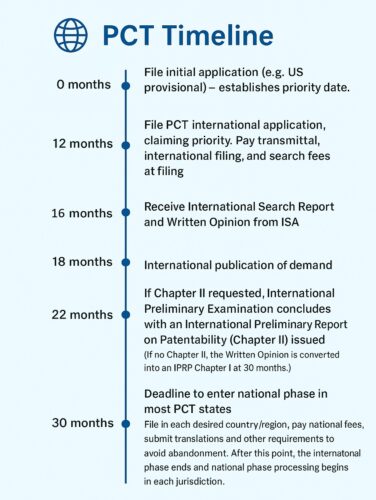

An opposition proceeding follows a structured timeline set by the TTAB. Below is a breakdown of each stage in chronological order, starting from the trademark’s publication in the Official Gazette to the conclusion of the case. Understanding this timeline is vital, as missing a deadline can be fatal to an opposer’s case or an applicant’s defense. The standard process assumes no unusual delays or extensions beyond those normally allowed.

Once a trademark application clears the USPTO examining attorney’s review and is approved, it is published in the Official Gazette. Publication is a critical trigger point: it marks the beginning of a 30-day opposition period. During this window, anyone who believes they would be harmed by the registration can oppose the mark. The publication is essentially the USPTO’s way of asking, “Does anyone have a legal reason this mark should not be registered?” If no opposition or extension request is filed within this period, the application will proceed to registration after the 30 days or to a Notice of Allowance in the case of intent-to-use applications.

Because the opposition window is short, potential opposers should monitor the Official Gazette (which is published weekly) or use watch services to catch publication of potentially conflicting marks. If an interested party needs more time to decide or prepare an opposition, they can request an extension of time to extend the opposition deadline. By rule, an initial 30-day extension will be granted on request as long as the request is filed before the original 30-day period expires. Further extensions up to a total of 180 days from publication are possible with good cause or the consent of the trademark applicant. The TTAB allows a maximum of three extensions, capping the opposition period at 180 days from publication in total. For example, an opposer might first get a 30-day extension automatically, then request a 60-day extension for good cause, and perhaps a final 30 or 60 days with consent, not to exceed the 180-day limit. If no opposition is filed within the allowed time, the opportunity to oppose is lost. In that case, the only recourse for a third party would be to initiate a trademark cancellation proceeding after the mark registers or to file a letter of protest earlier during examination.

A Letter of Protest is an informal procedure separate from opposition. It allows a third party to submit evidence to the USPTO before publication, aiming to convince the examining attorney to refuse an application. However, once a mark is published, the formal way to object is through an opposition.

To kick off an opposition, the opposer must file a Notice of Opposition with the TTAB through the USPTO’s Trademark Center electronic filing system and pay the required filing fee. The fee is charged per class of goods/services in the application. As of 2025, the opposition fee is $700 per class for an opposition filed electronically. The Notice of Opposition is essentially the complaint in this legal proceeding. It should include the opposer’s identity and standing (their interest in the case), identification of the application being opposed, the grounds for opposition, and a clear statement of facts supporting those grounds. The Notice is usually formatted in numbered paragraphs like a lawsuit complaint. For instance, it might allege the opposer’s ownership of a prior trademark with registration or prior use details, and then allege that the applicant’s mark is confusingly similar to the opposer’s mark under §2(d) of the Act, among other claims.

Upon filing, the TTAB will institute the opposition proceeding. The TTAB assigns a proceeding number and issues an Institution Order. This order sets the schedule for the case, including the deadlines for the next steps: answer, discovery conference, etc. The TTAB also notifies the trademark applicant that its application is now opposed. If the opposition is filed via Trademark Center, the system will automatically serve a copy on the applicant or its attorney of record, and the Board will ensure the applicant is aware of the proceeding.

After an opposition is instituted, the ball is in the applicant’s court to respond. The trademark applicant, now effectively the defendant in the proceeding, must file an Answer to the Notice of Opposition, generally within 40 days of the TTAB’s notification of the opposition. The exact deadline will be given in the scheduling order. In the Answer, the applicant must respond to each allegation in the Notice, paragraph by paragraph, admitting what is true and denying what is contested. The applicant can also raise affirmative defenses, such as laches, estoppel, acquiescence, or that the opposer has no grounds/standing. If the applicant has a basis to do so, they may also file counterclaims, e.g., seeking to cancel the opposer’s trademark registration if relevant. The opposer would then need to answer any counterclaims in turn.

Failure to answer by the deadline is serious. If the applicant does not file an answer and doesn’t obtain an extension or otherwise respond, the TTAB can enter a default judgment, resulting in the opposition being sustained and the trademark application abandoned. Essentially, the opposer would win by default. The TTAB often sends a notice of default if an answer is late, giving the applicant a short window to show cause or file a late answer. But it’s best not to miss the deadline. Bottom line is that the applicant must respond in a timely manner to avoid losing the opposition automatically.

Once the pleadings (Notice and Answer) are on file, the case moves into the pre-trial stage. The TTAB rules require that the parties conduct a discovery conference early in the process, typically within 30 days after the answer’s due date. In this conference, the opposer and applicant and/or their attorneys discuss the case logistics: potential settlements, the scope of discovery, any agreements on procedures, and whether to pursue alternative dispute resolution. They also review the TTAB’s standard protective order, which automatically governs confidential information in the case, and can agree to any changes to it. The idea is to plan and simplify the upcoming discovery process. This meeting can be by phone or in person, and both parties are required to participate in good faith.

Shortly after the discovery conference, the parties exchange initial disclosures. Initial disclosures provide basic information on witnesses and documents each side may rely on, serving to jump-start the evidence exchange. These disclosures are due as set in the schedule, often 30 days after the discovery conference.

The discovery period is when each party gathers evidence to support its claims or defenses. In TTAB oppositions, the discovery phase typically lasts 180 days from the opening date set by the Board. During discovery, both the opposer and applicant (now effectively plaintiff and defendant) can use various discovery tools in an alternating fashion to obtain information:

Each side can pursue discovery to gather evidence of, for example, likelihood of confusion (surveys, evidence of actual confusion, details about use of the mark), the descriptiveness of a term, the intent of the applicant in adopting the mark, and so on. For instance, an opposer might serve interrogatories asking the applicant to explain the choice of its mark or to state whether it was aware of the opposer’s mark, which is relevant to a bad-faith adoption claim. The applicant might request documents showing the opposer’s use of its own mark to gauge strength or whether the opposer has actually been harmed.

The parties should respond to discovery requests within the time set by the rules (30 days from service). If a party believes the other is not providing proper responses, they can file a motion to compel with the Board. Parties can also stipulate to extensions of the discovery period or certain limits to streamline the case.

In some cases, either party may file a motion for summary judgment before trial if they believe there are no genuine disputes of material fact and that they are entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Summary judgment can avoid a full trial if, e.g., the opposer clearly lacks evidence on a required element. The TTAB allows summary judgment motions, but they must be filed before the party’s pre-trial disclosures are due. Notably, many TTAB oppositions settle or narrow during discovery. The parties might negotiate a coexistence agreement or an amendment to the application to resolve the conflict. Settlement can occur at any time; if a settlement is reached, the opposer may withdraw the opposition, ending the proceeding.

If the case isn’t disposed of on motion or settlement during discovery, it proceeds to trial, but “trial” at the TTAB doesn’t usually mean live courtroom battles. Instead, the TTAB trial phase is conducted through written testimony periods and evidence submission. The Board’s scheduling order will set sequential windows for each party to put in their evidence. The opposer, as the party with the burden of proof, goes first.

The standard schedule allocates:

These testimony periods happen in an alternating fashion without overlap. Each party must also serve pretrial disclosures shortly before their testimony period begins, identifying who will testify, etc., as required by the rules. Notably, live oral testimony in a TTAB hearing is rare. Evidence is typically submitted on paper (affidavits) or by deposition transcripts. This written record approach is a key difference between TTAB trademark trial procedure and a normal court trial.

All evidence submitted must comply with TTAB rules of evidence and procedure. For example, documents need to be properly authenticated or fall under a rule. Some documents can be submitted by notice of reliance, such as printed publications and official records. The TBMP provides detailed guidance on making evidentiary submissions.

After the testimony periods conclude and the evidentiary record is closed, the parties get to file trial briefs. Trial briefs are written arguments summarizing the facts and law, much like closing arguments in a trial. The briefing schedule, like the testimony, is sequential and staggered:

These briefs are critical, as they frame the case for the TTAB judges. The trial briefs should cite precedent, including TTAB decisions and Federal Circuit case law. For example, a brief on likelihood of confusion will likely cite the DuPont case factors and perhaps compare them to facts on record, and may cite past TTAB cases with similar mark comparisons to support its stance. Both sides might also cite the Trademark Act and regulations (e.g., 15 U.S.C. §1052(d) for confusion, §1052(e) for descriptiveness, etc.) to ground their arguments in law.

After briefing, either party may request oral argument before the Board, though this is not required. If an oral hearing is desired, a request must be filed. Oral hearings in TTAB cases are relatively rare: many cases are decided on the written record and briefs alone. When held, an oral hearing allows attorneys for both sides to present their arguments in person (or by video conference) to a panel of TTAB judges and answer the judges’ questions. The hearing is brief, typically allowing 30 minutes per side. It can be useful in complex cases, but for straightforward cases parties often waive it. If no oral argument is requested, the case will be decided on the papers.

If an oral hearing is held, no new evidence can be introduced at that stage. The hearing is limited to argument based on the record. The TTAB typically schedules the hearing a few months after briefing, if requested. Otherwise, once briefing (and any requested hearing) is done, the case is ready for decision.

The culmination of the opposition process is the TTAB’s decision. A panel of typically three administrative trademark judges will consider the evidence and arguments and issue a written decision. The decision will usually come several months after briefing is complete and any oral arguments are heard. On average, the TTAB aims to issue decisions around 3 to 6 months after the case is ready for decision, though complex cases can take longer.

In the decision, the TTAB will make findings on each claim. For example, if likelihood of confusion was alleged, the decision will analyze the DuPont factors and conclude whether confusion is likely or not. If multiple grounds were alleged, the Board might rule on each. The outcome will either be that the opposition is sustained, meaning the opposer wins and the trademark application is refused registration, or that the opposition is dismissed, meaning the applicant wins and the application can proceed to registration. The decision will also address any procedural or evidentiary issues raised.

Notably, the TTAB’s jurisdiction is limited to the registration issue. The Board cannot award damages, attorneys’ fees, or injunctions, and it does not decide the right to use a mark in commerce. So, if an opposer “wins,” the mark won’t register; if the applicant “wins,” the application can mature to registration, but that doesn’t grant the applicant the right to infringe on someone’s actual use. A decision favorable to the applicant just gives them the registration, which is evidence of their right to use. In other words, an opposition is about who gets a registration on the Principal Register, not about marketplace remedies.

Once the decision is rendered, the TTAB will send it to both parties. The losing party then has decisions to make about potential appeal or other actions.

If a party is dissatisfied with the TTAB’s final decision, they have the right to appeal. Under the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1071), there are two possible routes for appeal:

Importantly, if the losing party appeals to the Federal Circuit, they generally cannot later file a civil action on the same case, and vice versa. You get one choice of forum. However, a party who appealed an earlier TTAB decision to the Federal Circuit could still go to District Court on a later TTAB decision in the same case due to a remand. Snyder's-Lance, Inc. v. Frito-Lay North America, Inc., No. 19-2316 (4th Cir. 2021).

Business owners should note that a TTAB decision on likelihood of confusion or other grounds is not the same as a court ruling on infringement. However, TTAB findings can potentially be used in later litigation for issue preclusion in certain circumstances. In B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Indus., Inc., 575 U.S. 138 (2015), where the Supreme Court held that a TTAB decision on likelihood of confusion could preclude re-litigation of that issue in a subsequent trademark infringement lawsuit if the usages contested were materially the same.

The trademark opposition process provides a vital checkpoint in the trademark registration system, allowing businesses and individuals to protect their brands from potentially conflicting marks before those marks obtain the benefits of registration. If you are concerned about a competitor’s trademark application, it’s important to act promptly. If you do not file a trademark opposition during the allowed time, you will have to deal with a registered mark later. These proceedings often involve complex trademark law issues (likelihood of confusion analyses, evidentiary showings of use or fame, etc.). The experience of a seasoned trademark opposition attorneys to navigate opposition cases, as the rules and strategies can be nuanced and the outcome can significantly impact one’s branding rights. If you have a trademark opposition matter or other trademark issue, contact us for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney