When most business owners think of trademark disputes, they think of trademark infringement, which is the result of a similar trademark being used on similar goods or services. However, under U.S. trademark law, well-known brands are also protected against "trademark dilution". Famous marks cannot be used in connection with any goods or services without violating the federal Trademark Dilution Act. Unlike infringement, dilution does not require actual or likely confusion, competition between parties, or even actual economic injury. Instead, it protects against uses of a famous trademark that could weaken its distinctive quality or harm its owner’s reputation. We discuss herein how trademark dilution differs from infringement, and why understanding it matters for business owners.

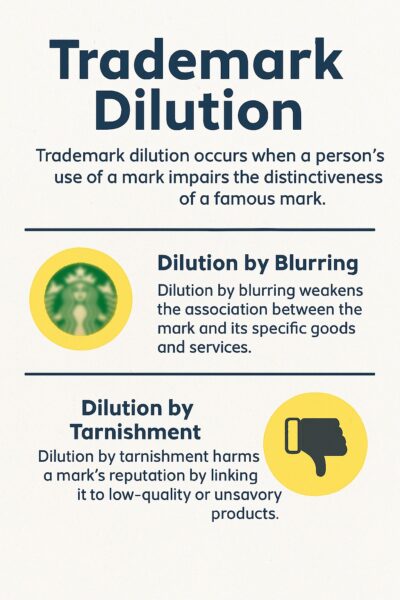

Trademark dilution is a legal concept that protects famous trademarks from unauthorized uses that, over time, could weaken their ability to serve as unique identifiers of their owner’s goods or services. Unlike traditional trademark infringement, which requires proof of a likelihood of confusion among consumers, dilution focuses on preserving the distinctive quality and reputation of a famous mark even when there is no confusion, competition, or actual economic injury.

Under the Federal Trademark Dilution Act of 1995, and later its amendment in the Trademark Dilution Revision Act (TDRA) of 2006, the law prohibits the use of a mark or trade name that is sufficiently similar to a famous trademark if such use is likely to blur its distinctiveness or tarnish its reputation. This protection applies regardless of whether the junior user is competing with the famous mark’s owner or whether the use causes actual or likely confusion.

Federal law recognizes two types of trademark dilution: dilution by blurring and dilution by tarnishment.

Dilution by blurring occurs when the use of a mark that is similar to a famous trademark weakens the strength of the famous mark’s association with its specific goods or services. Importantly, this type of dilution does not depend on a likelihood of confusion among consumers. Instead, the harm lies in the gradual erosion of the famous mark’s uniqueness as a source identifier.

For example, if a small business launched “Google Plumbing” or “Rolex Coffee,” even if consumers are not confused into thinking these companies are affiliated with Google or Rolex, the mere association of these marks with unrelated goods and services could diminish their distinctiveness. Over time, consumers may no longer instantly associate the famous mark with its original source, undermining its commercial impact.

Under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(2)(B), the Trademark Dilution Revision Act defines blurring as “an association arising from the similarity between a mark or trade name and a famous mark that impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark.” Courts evaluating blurring look at factors like the degree of similarity, the level of recognition of the famous mark, and whether the use of the mark by the defendant is likely to create mental associations that impair the famous mark’s ability to stand out.

Courts look for actual association between the junior and senior marks to assess blurring. However, research suggests that mere association may not always impair the famous mark’s distinctiveness.

Dilution by tarnishment happens when the use of a mark similar to a famous trademark creates an undesirable association that harms the famous mark’s reputation. Unlike traditional trademark infringement, tarnishment does not require proof of a likelihood of confusion or competition between the parties. Instead, it focuses on whether the defendant’s use casts the famous mark in an unwholesome or negative light.

For instance, using a luxury brand name like “Chanel” in connection with low-quality or unsavory products, such as adult entertainment or shoddy merchandise, can damage the brand’s carefully cultivated image. Courts have noted that tarnishment often occurs when a famous trademark is linked to products of inferior quality or placed in offensive contexts.

Under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(2)(C), tarnishment is defined as “an association arising from the similarity between a mark or trade name and a famous mark that harms the reputation of the famous mark.” Courts consider whether the defendant’s use of the mark creates is likely to create negative connotations that erode the famous mark’s goodwill and standing in the marketplace.

Unlike trademark infringement, which focuses on actual or likely confusion among consumers, dilution applies even when there is no confusion or competition.

Trademark dilution and trademark infringement are distinct legal concepts with important differences for business owners to understand. In a traditional infringement case, the central issue is whether the defendant’s use of a mark creates actual or likely confusion among consumers as to the source of goods or services. In contrast, dilution does not require confusion, competition, or even actual harm. The focus is instead on whether the defendant’s use diminishes the uniqueness or tarnishes the reputation of the plaintiff’s mark, particularly when the mark is famous. Only famous marks that are widely recognized by the general consuming public, such as Coca-Cola or Google, qualify for this heightened protection. This distinction allows owners of famous marks to challenge uses that may gradually erode their brand’s strength, even outside their market.

Under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c) of the Trademark Dilution Revision Act (TDRA), the owner of a famous mark can bring a dilution claim when certain criteria are met:

Importantly, the statute permits claims “regardless of the presence or absence of actual or likely confusion, competition, or actual economic injury.”

Not every trademark qualifies. To be considered famous, courts look at factors such as:

Examples of famous trademarks include Coca-Cola, Google, and Nike.

The Trademark Dilution Revision Act (TDRA) provides several important defenses that can shield a defendant from liability in a dilution action. These defenses recognize the need to balance the rights of famous trademark owners with the public’s rights to free expression and fair competition.

These defenses limit the scope of dilution law and help preserve free speech.

A federal cause of action for trademark dilution gives owners of famous marks several powerful remedies under the Trademark Dilution Revision Act (TDRA).

These remedies are designed to preserve a famous mark’s distinctiveness and to deter unauthorized uses that may weaken its strength in the marketplace.

A federal trademark registration provides significant advantages for trademark owners pursuing dilution claims. Registration with the Trademark Office secures nationwide federal protection, making it easier for the owner of the mark to enforce rights against unauthorized uses that may blur or tarnish their brand. While federal protection under the TDRA is available even to unregistered famous marks, registration strengthens a plaintiff’s position by serving as prima facie evidence of ownership and distinctiveness. When courts are determining whether a mark qualifies as “famous” for dilution purposes, they often consider whether the mark is federally registered as part of the analysis, along with factors like advertising reach and market recognition.

Many scholars argue that dilution law gives trademark owners rights in gross, effectively allowing them to control the use of words or phrases far beyond their original market without requiring proof of actual economic injury. This level of protection has been compared to granting near-monopoly rights over language itself. Critics note it may suppress free speech, especially where non-commercial use is at issue, e.g., in cases involving parody, commentary, or other non-commercial use. Critics also argue that this broad scope facilitates unfair competition by the trademark owner and can stifle the market by preventing smaller businesses from using descriptive or evocative terms.

Many countries offer similar protection for famous trademarks. However, requirements for proving dilution and the scope of protection vary widely. Business owners with global brands should understand the geographic extent of dilution protection in different jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Trademark dilution is a bit of a niche area of trademark law. However, it is often raised in trademark disputes and should be understood by parties and attorneys alike. If you have a potential trademark dilution issue or other intellectual property law matter, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

"Mark and William are stellar in the capabilities, work ethic, character, knowledge, responsiveness, and quality of work. Hubby and I are incredibly grateful for them as they've done a phenomenal job working tirelessly over a time span of at least five years on a series of patents for hubby. Grateful that Fresno has such amazing patent attorneys! They're second to none and they never disappoint. Thank you, Mark, William, and your entire team!!"

Linda Guzman

Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights

FRESNO

7030 N. Fruit Ave.

Suite 110

Fresno, CA 93711

(559) 436-3800 | phone

BAKERSFIELD

1925 G. Street

Bakersfield, CA 93301

(661) 200-7724 | phone

SAN LUIS OBISPO

956 Walnut Street, 2nd Floor

San Luis Obispo, CA 93401

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SACRAMENTO

180 Promenade Circle, Suite 300

Sacramento, CA 95834

(916) 209-8525 | phone

MODESTO

1300 10th St., Suite F.

Modesto, CA 95345

(209) 286-0069 | phone

SANTA BARBARA

414 Olive Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

(805) 275-0943 | phone

SAN MATEO

1650 Borel Place, Suite 216

San Mateo, CA, CA 94402

(650) 398-1644. | phone

STOCKTON

110 N. San Joaquin St., 2nd Floor

Stockton, CA 95202

(209) 286-0069 | phone

PORTLAND

425 NW 10th Ave., Suite 200

Portland, OR 97209

(503) 343-9983 | phone

TACOMA

1201 Pacific Avenue, Suite 600

Tacoma, WA 98402

(253) 345-1545 | phone

KENNEWICK

1030 N Center Pkwy Suite N196

Kennewick, WA 99336

(509) 255-3442 | phone

2023 Sierra IP Law, PC - Patents, Trademarks & Copyrights - All Rights Reserved - Sitemap Privacy Lawyer Fresno, CA - Trademark Lawyer Modesto CA - Patent Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Patent Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Lawyer San Luis Obispo, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Tacoma WA - Internet Lawyer Bakersfield, CA - Trademark Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Patent Lawyer Sacramento, CA - Trademark Infringement Lawyer Sacrament CA - Patent Lawyer Tacoma WA - Intellectual Property Lawyer Tacoma WA - Trademark lawyer Tacoma WA - Portland Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Patent Attorney - Santa Barbara Trademark Attorney