The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) is an international treaty administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) that streamlines the process of seeking patent protection in multiple countries. Instead of filing separate patent applications in each country of interest, a PCT application allows an inventor to file one “international” patent application which has effect in over 150 PCT contracting states simultaneously. This system, often called the international patent system under the PCT, simplifies initial filing formalities and defers much of the cost and effort of pursuing patents in many countries. Importantly, the PCT does not itself grant an “international patent” (no such single global patent exists). The granting of patents remains under the control of each national or regional patent office during the “national phase” of the process. For U.S. applicants (e.g. businesses or inventors in the United States), the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) can act as a PCT receiving office to start the process, and the PCT framework is integrated into U.S. patent law. This article explains in accessible terms how the PCT works, its timeline and costs, and key requirements for U.S. applicants using the USPTO as the receiving office.

The PCT is used by companies of all sizes, universities, and individual inventors around the world when they seek international patent protection. It has become a cornerstone of international patent strategy. Every year there are hundreds of thousands of PCT international applications filed. For a business owner, the PCT is important because it provides a cost-effective and time-saving path to pursue patent rights in multiple countries. By filing one international application under the PCT, an applicant can essentially lock in a single earliest filing date (priority date) for an invention across many countries, and then delay the decision and expense of filing in each country by up to 18 additional months compared to the traditional route. This extra time can be invaluable for evaluating the invention’s commercial prospects and deciding in which countries to seek patents. In short, the PCT helps businesses seeking patent protection in multiple countries by simplifying the application process and giving them more time and information before entering numerous separate patent offices.

The Patent Cooperation Treaty is an international treaty first signed in 1970, now with more than 150 member countries (PCT contracting states). It created an international patent system that makes it possible to seek patent protection for an invention simultaneously in a large number of countries by filing a single “international” patent application. In essence, a PCT application is a unified initial filing that can later be pursued in many different countries. Any inventor or company who is a national or resident of a PCT contracting state can file a PCT application. U.S. applicants are eligible, as the United States has been a contracting state since 1978. A PCT application may be filed with your national patent office (the USPTO) or directly with WIPO’s International Bureau, which both act as PCT receiving Offices.

It is important to understand that the PCT itself does not grant a patent. Instead, it delays and coordinates the process of pursuing patents in the PCT contracting countries. The applicant must still enter the national phase in each country or region where protection is desired, and pursue the application under that country’s national law. The PCT thus provides a unified filing and preliminary examination process (the international phase), followed by separate patent applications in each country/region (national phase) where you want patent rights for the claimed invention.

By filing a PCT international application, an inventor effectively secures a filing date in all PCT member countries at once, and gains the benefit of a centralized search and preliminary examination, before deciding on separate national applications in individual countries. The system is administered by WIPO in Geneva, and is used worldwide as a standard route for international patent filings.

For business owners contemplating global markets, the PCT system offers several advantages over filing separate national patent applications in each country:

You file one application, in one language, and pay one set of initial fees, instead of filing many applications with different patent offices simultaneously. This simpler and more cost-effective approach reduces duplicate effort. WIPO handles a formality examination of the application, so if your PCT application meets the PCT’s form requirements, it cannot be rejected on formal grounds by any national office later.

As part of the PCT’s international phase, a qualified patent office will conduct an International Search and provide a report on relevant prior art along with a Written Opinion on the invention’s patentability. This happens early, before you spend money on multiple national filings. The search report and opinion give valuable insight into the strengths and weaknesses of your claimed invention, allowing you to make informed business decisions (e.g. whether to proceed in certain countries, or perhaps to modify your claims). You even have an option for an International Preliminary Examination (an additional, interactive examination – see below) to further assess or bolster your application before national phase entry.

Perhaps the biggest practical benefit is time. Under PCT, you usually gain an additional 18 months after your initial filing before you must incur the expenses of national filings. In a typical scenario, you have 12 months from your earliest patent application to file a PCT (this 12-month rule comes from the Paris Convention priority period), and the PCT gives you up to 30 months from the priority date (in most countries) to enter the national phase. That 30-month deadline is 18 months longer than the 12-month Paris Convention deadline would have been if you filed separate foreign applications directly. During these 18 extra months, the international search report and publication can help you gauge the invention’s patentability and market potential. You can use this time to seek investors, evaluate commercial interest, or decide to drop the application if prospects look unfavorable – thereby saving the cost of filings in many countries. In short, the PCT buys you time and information.

While the PCT application is pending, it maintains your rights in all designated states without further action. You do not have to pay separate filing fees or hire local attorneys in each country at the start. The international application is treated as a pending application in all PCT countries simultaneously. This global effect means no need to rush translations or incur local fees early on, and it preserves the option to proceed in any PCT country later.

When you do enter national phases, the PCT search report and any international examination report accompany your application into each patent office. National examiners consider these PCT work products, which often reduces duplication of effort. In some cases, if the PCT results are favorable, national phase examination may be accelerated or smoother. Many patent offices participate in the Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH), allowing you to fast-track examination by leveraging a positive PCT opinion or report. Essentially, the PCT centralizes the early search and (optional) examination, which can make the subsequent national phase more efficient.

At 18 months from the priority date, the PCT application is published internationally by WIPO. This publication puts the world on notice of your invention. Competitors and potential licensees can learn of your application by searching WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE database once it’s published. Early publication combined with the credibility of a WIPO search report may help attract partners or deter infringers, since third parties can evaluate the potential patentability of the claimed invention based on the PCT publication. You also have the option to indicate on PATENTSCOPE that you seek licensing opportunities, effectively advertising your invention to the world.

In summary, the PCT offers simplicity, time efficiency, and strategic advantages for applicants seeking patents in multiple countries. It is simpler, easier and more cost-effective than filing separate applications country-by-country, especially for U.S. businesses looking to expand their patent protection globally.

To navigate the PCT process, it helps to know some basic terminology and the entities involved:

This is the patent office where you file your PCT application. Each PCT member country’s patent office can act as a receiving Office for its own nationals/residents. For example, the USPTO is the receiving Office (RO/US) for U.S. applicants. WIPO’s International Bureau can also directly receive applications in some cases. The receiving Office checks that your application meets minimum requirements (e.g., that you’ve included at least a description and the applicant is entitled to file) and then assigns an international filing date if all formal requirements required by PCT Article 11 are met.

The date your PCT application is officially filed at the receiving Office. If the application meets the formality requirements, the international filing date is accorded and serves as the effective filing date for all designated countries. This date is very important; it’s equivalent to a filing date in each PCT country. If you are claiming priority from an earlier application (e.g., a US patent application), you must file the PCT within 12 months of that earlier application’s date to preserve your priority.

This is WIPO’s office in Geneva that centrally administers PCT applications. The IB acts as a clearinghouse: it publishes the applications, communicates documents to all designated countries’ patent offices, and keeps the master file. Once you file with a receiving Office, the application data is sent to the IB. The IB is also a possible receiving Office itself for applicants who choose to file directly with WIPO. The IB handles the international publication of PCT applications at 18 months and stores the application in its database.

This is the patent office that performs the international search on your PCT application. ISAs are major patent offices appointed to conduct PCT searches (for example, the USPTO, European Patent Office, JPO, and KIPO are ISAs). Not every ISA is available for every applicant, which ISA is competent can depend on where you filed your PCT. U.S. applicants filing at RO/US currently can choose the USPTO itself as ISA or one of several other offices, such as EPO, KIPO, Australia, Singapore, etc., subject to agreements. The ISA will search patent literature and technical publications to find prior art relevant to your invention.

This is the report prepared by the ISA listing prior art documents (patents, publications) that may affect the patentability of your invention. The ISR gives for each reference an indication of its relevance to novelty or inventive step. It’s essentially a focused prior art search result. The ISA aims to issue the ISR along with a Written Opinion typically within about 16 months from your priority date (or about 9 months from the PCT filing date). The ISR is later published by WIPO, usually together with your application at 18 months.

Along with the ISR, the ISA provides a written opinion analyzing whether your claimed invention appears to meet the criteria of novelty, inventive step (non-obviousness), and industrial applicability. This written opinion is preliminary and non-binding, but it’s very useful: it explains the examiner’s view on each claim’s patentability in light of the prior art found. As an applicant, you don’t have to respond to the written opinion during the international phase, unless you choose to request further examination, but you can use it to guide amendments. If you take no further action, this written opinion will later be converted into an “international preliminary report on patentability (Chapter I)” at the end of the international phase, which is communicated to all the national offices.

WIPO publishes the PCT application promptly after 18 months from the earliest priority date. The publication includes the description, claims, any drawings, and also the ISR (if it’s ready in time) and the applicant’s abstract. It is published in one of the 10 languages of publication. For example, if you filed in English, it publishes in English. After publication, the content is publicly available on WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE database. Prior to 18 months, the PCT file remains confidential, unless you request early publication or access. Publication at 18 months is a standard practice also for regular national applications in many countries, including U.S., aligning with the principle that patent applications are made public 18 months after filing.

If you decide to proceed with Chapter II, International Preliminary Examination, you will file a demand for examination and usually amend your application or argue against the ISA’s opinion. The IPEA is an office that conducts this second-round examination. Not all applicants use Chapter II, but it can be beneficial if the ISA’s written opinion was negative and you wish to improve the application before national phase. The International Preliminary Examining Authority will consider your amendments and arguments, possibly correspond with you or even hold an interview, and then issue an International Preliminary Report on Patentability (Chapter II).

IPRP Chapter I: If you do not request a Chapter II exam, the WIPO will issue an IPRP (Chapter I) which is basically a copy of the ISA’s final written opinion (translated into English if necessary) at the end of the international phase. This report, along with the ISR, is sent to all designated offices for their reference.

IPRP Chapter II: If you do file a demand for preliminary examination (Chapter II), the outcome is an International Preliminary Report on Patentability (Chapter II) issued by the IPEA. This report will state the examiner’s patentability opinion on each claim after considering any amendments you made. Like the Chapter I report, it is non-binding on national offices, but it provides a stronger basis if positive. A favorable Chapter II IPRP can significantly bolster your case going into national exams. National patent offices often give the IPRP weight, even though they will do their own examination. If the report is negative, it at least forewarns you of likely issues.

This refers to the stage after the PCT international phase where you actually pursue patent grants in individual countries or regions. “Entering the national phase” means filing the necessary documents and fees with a national or regional (e.g., the European Patent Office) patent office, based on your PCT application. The national phase deadline is typically 30 months from the priority date, though a few offices have 31 months or allow slight extensions. During national phase, each patent office examines the application under its own national law and requirements. The international stage PCT documents and analysis will be available to them to consider, but each office makes its own decision on granting a patent. Essentially, the PCT application splits into multiple “daughter” applications in the national phase, one in each desired country/region.

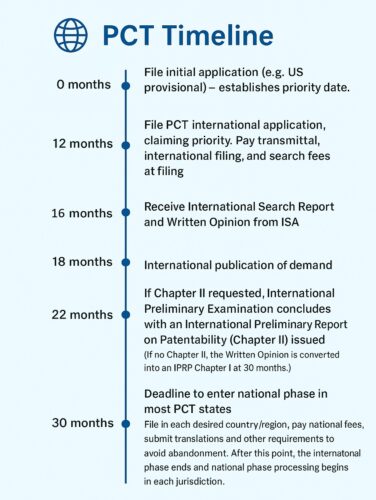

For clarity, we’ll consider a typical scenario for a U.S. applicant and outline the PCT process timeline with key milestones, requirements, and fees. Assume you have an initial U.S. patent filing (for example, a provisional or non-provisional application) and you want international protection:

Initial Application Filed. Often, applicants first file a national application in their home country to establish an initial filing date. For instance, you might file a U.S. provisional application or a U.S. non-provisional application. This date is the priority date for subsequent filings. Under the Paris Convention, you have 12 months from this date to file a PCT application to claim its priority. If you don’t have an earlier application, your PCT filing itself can be the first filing and the PCT filing date is the priority date.

Before 12 months from the priority date expires, you must file your PCT international application if you want to claim priority to the earlier national application. For US applicants, this PCT filing is often done via the USPTO as the receiving Office (RO/US). Requirements at filing: You need to submit the PCT Request form (which is basically a cover sheet with bibliographic data, inventor/applicant information, etc.), a specification (description, claims, drawings if any, abstract) – which can be a direct copy of your prior application or updated, and usually an abstract. You also must pay the international fees at this stage. Typically, there are three types of fees due upon PCT filing:

Transmittal Fee: a small fee for the receiving Office (USPTO) handling the filing. For example, the USPTO’s transmittal fee is a few hundred dollars (often around $240 for electronic filing; check current USPTO fee schedule).

International Filing Fee: a WIPO fee for processing the application internationally. This is a fixed fee for all applicants worldwide, denominated in Swiss Francs (CHF). As of the PCT Applicant’s Guide, the base international filing fee is 1,330 Swiss francs (about $1,400, but varies with exchange rates) for up to 30 pages. There is an additional fee per page if your application exceeds 30 pages. This fee is paid to the receiving Office, which is then forwarded to WIPO.

Search Fee: the fee for the International Searching Authority to perform the prior art search. This amount depends on which ISA is chosen and can range roughly from $150 to $2,000. For example, if the ISA is the USPTO, the search fee (per USPTO’s fee schedule) might be around $2200; if the ISA is the European Patent Office, it’s about EUR 1,775; some other ISAs are less costly. The applicant typically selects the ISA in the request form. The search fee is paid at filing to the receiving Office, which is forwarded to the ISA.

Optional Fees: If you file electronically using approved software (which most applicants do via ePCT or USPTO’s electronic filing system), you may receive a reduction in the international filing fee. Also, if you qualify as a small entity or reside in certain countries, fee reductions might apply (e.g., certain developing country applicants get 90% reduction in WIPO fees).

After filing, an international filing date is accorded (assuming all formal requirements are met). The USPTO (RO/US) will assign an international application number and confirm your international filing date, which, crucially, is the date that will count as the effective filing date in all PCT countries. If something is missing, the receiving Office may give you a chance to correct it and still get the date; the conditions for obtaining a filing date are set by PCT Article 11.

The receiving Office processes your application, confirms all parts are present, and then forward it to the International Searching Authority (ISA) you selected. The ISA will typically start the international search for prior art. You will receive an acknowledgment of your PCT filing (with the PCT number and filing date) and later possibly a notice if anything needs to be fixed (e.g., missing pages or fee issues). If all is in order, you mostly wait for the search results. The priority document (your earlier application) also needs to be provided to WIPO, and is often the receiving Office will handle transmitting an electronic copy if the priority application was, e.g., a US application, via the priority document exchange system. Otherwise you may need to furnish a copy or request retrieval).

The ISA aims to issue the International Search Report (ISR) along with the Written Opinion (WO) by about 16 months from the priority date or roughly 9 months after the PCT filing. The ISR is a list of prior art references (patents, publications) relevant to your claimed invention, with indications of their relevance. The Written Opinion is a detailed initial examination analysis of your claims against the prior art, essentially stating whether your invention is novel, non-obvious, and industrially applicable, and explaining any issues claim by claim. This written opinion is not public at this point and is not an official rejection, but it gives you a preview of what an examiner thinks. In response to the ISR and written opinion, you have the option to do nothing (e.g., if the report is favorable), or prepare and file claim amendments and/or submit arguments against any patentability issues raised in the report.

Whether or not you have the search report by then, at 18 months from your priority date, WIPO will publish your PCT application electronically. The publication (identified as “WO [year]/[#####]”) includes your application text and any figures, and if the International Search Report is ready, it is published as an appendix. If the ISR wasn’t ready by 18 months, the application still publishes, and the ISR will be published separately later when available. The publication is in the public domain via PATENTSCOPE. From this point on, your invention’s details are public worldwide, and you have “patent pending” status internationally. Third parties can now see the results of the search, which can inform their actions or interest.

Costs at this stage: There is no additional fee for publication itself, the filing fee covered WIPO’s processing. However, if your application was filed in a language not accepted by your chosen ISA, you might have paid a translation cost for search purposes earlier. Most U.S. applicants file in English, so that’s usually not an issue since USPTO or EPO as ISA accept English. Also, if you decide around this time that you want to withdraw the application (to avoid publication, perhaps because the invention is no longer pursued or the ISR was very negative), you must do so before the 18-month mark. Otherwise, publication will occur and the application will be public.

If you choose to use the optional Chapter II procedure and request an International Preliminary Examination, you need to file a demand by the later of 22 months from the priority date or 3 months from the transmittal of the ISR. In practice, since the ISR usually arrives by 16 months, you have until around 19–22 months to decide on Chapter II.

Why file a demand? This is useful if the Written Opinion from the ISA was negative or if you want to amend the claims and get a second opinion on patentability before entering national phases. By filing the demand, you get to engage with an International Preliminary Examining Authority (IPEA) and potentially argue your case or amend claims.

Requirements and fees for Chapter II: You must file a demand form (there’s a PCT form for Chapter II demand) and usually submit any claim amendments (Article 34 amendments) you want to make in light of the search report. You’ll need to pay:

Once the demand is filed and fees paid, the IPEA will perform an international preliminary examination. This can involve at least one office action in the international phase: the examiner will review your amendments/arguments in view of the objections raised in the written opinion, possibly raise new issues, and may communicate with you. You have a chance to respond, and there may even be an interview with the examiner. Chapter II provides the only opportunity to have dialogue with an examiner during the international phase. Many applicants skip Chapter II to save cost, but those who want a cleaner application going into national phase or who want to test amendments globally, often use it.

If Chapter II was used, the IPEA will issue the International Preliminary Report on Patentability (IPRP Chapter II) by around 28 months from the priority date. This report will state, for each claim, whether it meets the criteria of novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability in the examiner’s opinion. It will be shared with all the elected Offices: the countries you intend to enter. If you did not file a Chapter II demand, then an IPRP Chapter I will be prepared, which is essentially a copy of the ISA’s written opinion. Either way, by 30 months at the latest, the international phase concludes with a dossier of search and examination documents that national offices can use.

Thirty months from your earliest priority date is the typical deadline to enter the national phase in each country or regional office you choose. “Entering national phase” means you must take action in each desired jurisdiction to continue prosecution of the application there. What must you do? According to PCT Article 22 and related national laws:

It’s important to meet the 30-month deadline. If you miss it in a given country, the application can lapse in that country, and be treated as withdrawn/abandoned. Some jurisdictions have grace periods or remedies, for example, the U.S. allows the acceptance of a late national stage entry after 30 months if the delay was unintentional, via petition and payment of a late fee under 35 U.S.C. § 371(d). But such leniency is not universal, many countries strictly bar late entry. Therefore, patent applicants should diarize the 30-month date and take action in time.

This is where the major expenses occur. You now must pay separate fees in each selected country. Costs include official filing fees (vary by office), translation costs (if needed), and local attorney fees for handling the filings. The national phase fees are the most significant pre-grant costs; they can far exceed the earlier PCT costs. However, some national offices offer reduced fees for PCT entries compared to direct filings, recognizing the work already done internationally. For example, if an office benefitted from the international search, they might charge a lower search/exam fee nationally. Nonetheless, applicants should budget carefully; entering, say, Europe, China, Japan, Canada, and Australia could collectively cost tens of thousands of dollars in filing and translation fees.

At the 30-month juncture, you effectively decide in which countries or regions you want to pursue actual patents. Many applicants will choose a handful of key markets based on business strategy. The PCT helped delay this big expense and decision until this point. Now, those national applications will be prosecuted individually in each jurisdiction’s patent office.

After entry, each patent office will process the application as a national application (often assigning it a local application number). They will usually refer to the PCT search report and may use the PCT examiner’s work as a starting point, but they will apply their own patent law standards. For example, the USPTO will have its examiners examine the application under U.S. law (35 U.S.C. §§ 101, 102, 103, 112, etc.), the European Patent Office will examine under the European Patent Convention, and so on. You or your local attorneys will correspond with each office, respond to rejections, and prosecute the application to grant as you would with any patent application.

The timeline and outcome now vary by country: some offices might grant a patent within a year or two, others might take longer. Each resulting patent is a separate patent, enforced in that country or region. Maintenance fees will have to be paid in each jurisdiction to keep those patents in force.

Below is a quick visual summary of key PCT timeline points using the earliest priority date as time zero:

Throughout this timeline, keep in mind specific national rules. For instance, some countries have slightly different deadlines: a few allow 31 months, like the EPO. You can consult the PCT Applicant’s Guide for any particular country’s requirements and time limits. WIPO provides detailed national chapters in the Guide outlining each state’s rules.

U.S. business owners filing via the USPTO should note a few specific points:

The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) is a powerful tool for U.S. businesses and inventors looking to protect an invention in multiple countries. It provides a unified international patent application process that simplifies filing and delays the need to make expensive decisions about country-by-country patent filings in the over 150 PCT contracting states. By using the PCT, a company can seek patent protection in multiple countries simultaneously in a cost-effective manner.

It is important to remember that ultimate patent protection remains territorial. There is no international patent that is issued. You must pursue patents in each target country or region, under their laws and procedures, to actually get patents granted. The PCT greatly facilitates and coordinates this process, but it doesn’t eliminate it.

In planning an international patent strategy, business owners should consider the PCT’s benefits: one application, one search, delayed costs, and global reach. In virtually all cases where protection in multiple countries is desired, the PCT is the recommended route. It is a flexible, user-friendly international treaty that makes the complex world of international patents more accessible to innovators. If you are considering pursuing foreign patent rights, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

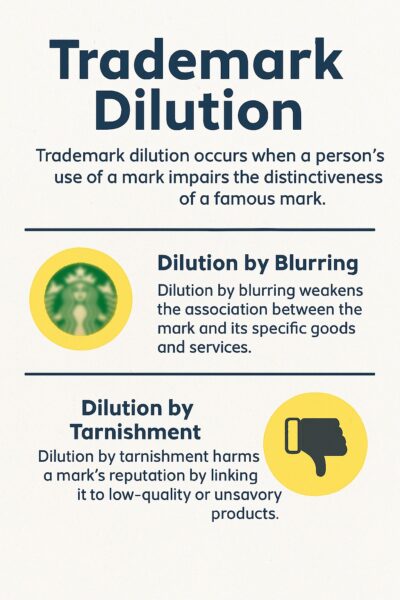

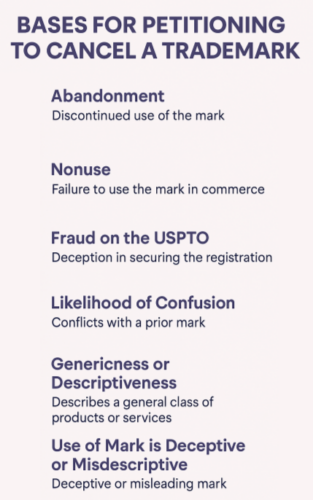

Every business owner choosing a brand name or logo should understand the trademark concept of likelihood of confusion. This is the legal standard U.S. courts and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) use to decide if two trademarks are too similar. If consumers would likely confuse the source of goods or services bearing two similar marks, then a conflict exists under trademark law. The underlying reason that trademark law prevents such confusion is to ensure consumers get accurate information about a product’s source. The law prevents such confusion primarily to protect consumers from being misled, while also safeguarding fair competition and business goodwill.

The principle of blocking confusingly similar marks has roots in 19th-century common law. Early trademark cases grew out of the law of unfair competition, particularly the doctrine of passing off, which essentially forbids one trader from misrepresenting their goods as someone else’s. As an English court famously stated in 1842, “A man is not to sell his own goods under the pretence that they are the goods of another man”. Perry v. Truefitt (1842) 6 Beav. 66, 73.

The fundamental goal is to keep the marketplace honest and efficient for buyers. Trademarks (brand names, logos, etc.) serve as source-identifiers: they tell you who made a product or provides a service. When you see a familiar brand on a package, you assume it comes from the same source as all other products with that brand (think of Nike shoes, Hilton hotels, and Toyota vehicles). This confidence lets consumers make quick, informed choices. In economic terms, a distinctive trademark reduces consumer search costs. Shoppers don’t have to investigate the origin or quality of every product anew; the brand name carries that information and the company’s reputation. Businesses, in turn, are motivated to maintain quality and consistency, since their name is what customers rely on. In short, strong, non-confusing trademarks make shopping easier and reward companies for building goodwill with consumers.

Under U.S. trademark law, "likelihood of confusion" refers to the probability that consumers will be misled into believing that two different products or services come from the same source. The core question is whether an ordinary prudent consumer in the marketplace would reasonably expect the two marks (e.g. brand names or logos) to come from one company or affiliated companies. If such consumer confusion is likely, the law deems the marks confusingly similar. The law does not require proof that consumers are actually confused; it only requires showing that confusion is likely to happen.

For example, imagine one coffee shop is named “Bean Bazaar” and another coffee shop opens nearby as “Bean Bizarre”. Even though the second name is spelled differently, they are phonetically similar and offer the same services. Customers could easily assume the two cafes are related. They might think the new cafe is a second location or a spin-off of “Bean Bazaar.” In this scenario, there is a strong possibility that consumer confusion would occur.

Likelihood of confusion is the linchpin of trademark infringement cases. Under the federal Lanham Act (the U.S. Trademark Act), a trademark owner can stop others from using a mark if that use “is likely to cause confusion or mistake or to deceive” consumers about the source of the goods. In an infringement lawsuit, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant’s allegedly infringing mark is likely to confuse consumers. If the plaintiff succeeds, the court can order the infringer to stop using the mark and potentially pay damages. If the trademark owner can show instances of actual consumer confusion, the law recognizes that damage to the brand may already be done.

Courts commonly articulate the test as whether the buying public would likely believe the two products or services came from the same source. For instance, in Bean Bazaar - Bean Bizarre example, a court would ask whether an average customer exercising ordinary caution think these products come from the same company? If yes, the trademark owner has a strong infringement case. If no, then infringement will not be found.

Likelihood of confusion also matters when you apply to register a trademark. The USPTO examining attorney will perform a trademark search of existing marks. If the examiner finds a previously registered mark (or pending application) that is confusingly similar to your proposed mark, your application will be refused on likelihood of confusion grounds. This is often called a “Section 2(d) refusal,” referring to the section of the Lanham Act that bars registration of a mark that is likely to cause confusion with an existing mark. You’ll receive an office action explaining the conflict and will have to argue why your mark is not confusingly similar or else your registration will not go through.

For example, if you try to register “Omega Electronics” and there’s an active trademark registration for “Omega Electric” selling related products, the Trademark Office will issue a likelihood of confusion refusal. Under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d), no new mark can be registered if it “so resembles a mark registered in the Patent and Trademark Office… as to be likely, when used on or in connection with the goods of the applicant, to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive.” In essence, the USPTO is trying to protect consumers and senior trademark owners by preventing look-alike or sound-alike marks from getting on the federal register.

Just like courts, the USPTO uses a multi-factor analysis to assess proposed trademarks. These are known as the DuPont factors, from the case In re E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. 476 F.2d 1357 (CCPA 1973). The examining attorney will compare the marks in appearance, sound, meaning, and commercial impression, evaluate the relatedness of the goods or services, and consider other relevant factors that might indicate potential confusion. If, after weighing the factors, the examiner believes confusion is likely, the application is denied. This is why conducting a thorough trademark search before filing an application and before choosing a trademark and brand is so important. Prudence can save you from investing in a name that the USPTO or courts would deem too close to an existing mark.

To decide whether confusion exists between two marks, courts and the USPTO use a multi-factor test. There is no single bright-line rule. Several important factors relating to trademark confusion are evaluated. A famous example is the Sleekcraft factors, originating from the case AMF, Inc. v. Sleekcraft Boats, 599 F.2d 341 (9th Cir. 1979), which set out a framework that many courts follow. Most U.S. jurisdictions have a similar list (the Polaroid factors in the Second Circuit , the Lapp factors in the Third Circuit, etc.), but all share common considerations. The USPTO’s analysis under the DuPont factors is largely similar to the court tests. It is critical to note that not all factors will be relevant in every case, and no one factor is dispositive. Decision-makers will look at the overall picture of whether the consumer confusion is likely.

Here are the primary factors (the “Sleekcraft” factors) that are typically considered in a confusion analysis:

These factors are a guide rather than a checklist. Next, we’ll explore each of the major factors in turn, along with examples and key cases, to see how they affect the confusion analysis.

Trademarks vary in strength. A unique, distinctive mark has a wider scope of trademark protection, while a common or weak mark gets a narrow scope. The law categorizes marks along a spectrum of distinctiveness:

A strong mark (arbitrary, fanciful, or well-known with secondary meaning) will typically enjoy greater protection, meaning it can stop others from using even somewhat similar marks on related goods. A weak mark (e.g., descriptive without secondary meaning, or a mark used by many others in the field) will have a harder time claiming exclusivity. For example, a hypothetical brand “National Electronics” would be considered weak if many companies use “National” in their names. By contrast, a unique brand like “Xybernaut” for electronics is inherently strong. In one case, a cleaning service branded “Maid in America” (a descriptive wordplay) was deemed too descriptive and lacking secondary meaning, and the owner failed to prove infringement on that basis. The bottom line: the more distinctive your mark, the easier it is to prevent confusingly similar imitations.

One of the most important factors in any likelihood of confusion case is how similar the two marks are. To determine this, the marks are compared in their entirety, focusing on their appearance, sound, connotation (meaning), and overall commercial impression. Minor differences often do not suffice to avoid confusion if the overall impression is similar.

When evaluating similarity, courts and the USPTO consider the marks as consumers would encounter them in the marketplace. This means even if two marks have slight spelling differences or additional words, they could still be deemed essentially the same mark in the minds of consumers. Pronunciation is especially influential: marks that sound alike can confuse listeners even if spelled differently. For instance, “SUN Bank” and “Son Bank” would be nearly indistinguishable when spoken aloud. The same goes for marks with similar meanings or images (connotation). If one brand is called “Valiantheart Beer” and another is “Braveheart Ale”, the shared concept of courage could create a similar mental image or impression for consumers.

Courts will typically compare the marks side by side on these aspects:

If the dominant portion of the marks is the same, confusion is more likely. For example, adding a common suffix or changing one letter usually won’t avoid confusion: “Magnavox” vs. “Multivox”, “Travel Planner” vs. “The Travel Planner”, or “Maternally Yours” vs. “Your Maternity Shop” were all found to be confusingly similar pairs. In the Maternally Yours case, a maternity clothing retailer named Maternally Yours stopped a competitor from using Your Maternity Shop, even though the phrasing was slightly different, the court noted the same words just rearranged still misled customers. Maternally Yours, Inc., v. Your Maternity Shop, Inc., 234 F.2d 538 (2d Cir. 1956). Likewise, simply adding a small prefix or suffix might not change the mark’s identity in consumers’ minds. If someone tried to sell coffee under the name “Starbucks Café” versus the famous “Starbucks”, the extra word doesn’t prevent consumer perception of a link to the Starbucks brand.

Even if two marks are very similar, confusion might not occur if they are used on completely different types of goods or services. This factor looks at how related the goods or services are and whether they occupy the same or overlapping market. The basic idea: the more the products compete or are marketed in similar channels, the more likely consumers will assume a common source.

Consider these scenarios:

A classic example: “Delta” is used as a mark by both an airline and a faucet manufacturer, but the goods and services contexts are so different that consumers don’t assume a connection. In contrast, when the fast-food giant McDonald’s objected to a hotel chain’s plan to open budget hotels under the name “McSleep”, a court agreed that consumers might assume McDonald’s (famous for the “Mc-” family of brands like McNuggets, McMuffin, etc.) was expanding into hotel services. Quality Inns International, Inc. v. McDonald's Corp., 695 F. Supp. 198 (D. Md. 1988). The federally registered McDonald’s mark was so well-known and strong that even a different service (motels) could trigger an association. This shows that a very famous mark have more brand reach across goods and services. People could believe McDonald’s had a hand in anything starting with “Mc.” So, the more closely related the product lines or the more expansive the senior brand’s reputation, the more a similar mark will create confusion.

Additionally, this factor examines the overlap in marketing channels and customer base. If both companies advertise in the same magazines, sell in the same department store chains, or target the same demographic, a consumer could encounter both products in the same context and mistakenly think they are connected. On the other hand, if one product is sold only in upscale boutiques and the other in discount stores, or one is B2B sales and the other retail, the separation may reduce confusion.

In sum, the closer the marketplace proximity, the greater the chance that consumers will assume a single source. Businesses should be cautious if they choose a name similar to another company that’s even tangentially related to their line of business, especially if that company might bridge the gap and enter your market.

While a plaintiff doesn’t need to show any instances of real-world confusion to win an infringement case, any direct evidence of actual confusion can be extremely persuasive. Actual confusion means customers truly have been misled. For example, mistaking one brand for another, misdirected phone calls or emails, or survey results showing a significant number of consumers believed the two companies were connected. If such evidence exists, it strongly supports the argument that the similarity of the marks constitutes likelihood of confusion. As one source explains, proof that the average reasonably prudent consumer is confused is powerful evidence of infringement.

Courts often say actual confusion is the best evidence of likelihood of confusion. However, it’s important to remember that it is not required to prove a case. Many infringement cases are decided without any documented instances of confused consumers. For example, a company might sue shortly after the junior user begins using the mark and there may not have been time for actual confusion to manifest. In such cases, the court will rely on the likelihood factors, expert testimony, and consumer surveys rather than waiting for customers to be misled in the real world.

In practice, companies sometimes commission consumer surveys in litigation to gauge actual confusion. These surveys ask a sample of target customers questions to see if they believe two products come from the same source. While survey evidence can be direct evidence of confusion, its reliability can be contested, and a poor survey can even hurt the plaintiff’s case. Nonetheless, actual confusion remains a crucial factor: if you receive reports that customers are truly mixing up your product with another brand, that’s a red flag that your marks are too close.

If a plaintiff is able to show actual confusion, it can tip the scales. Even a few incidents, such as a shopper returning a product to the wrong company, or consumers commenting “Oh, I thought your brands were the same”, can carry considerable weight. Large-scale evidence like survey results or a pattern of mix-ups is even more compelling. Conversely, the absence of any known confusion after a long time of coexistence might suggest that confusion is less likely. The concept of long-term co-existence without any consumer confusion is also a factor considered under the likelihood of confusion analysis.

Trademark law also looks at the intent of the junior user (the alleged infringer). If the defendant intentionally copied or chose a mark to create confusion with the senior user’s mark, courts view that as evidence that confusion is likely. After all, if someone tries to ride on the coattails of an established brand, it implies they believe consumers will mistake the two and that they will benefit from that misassociation. Deliberate adoption of a similar name, especially with evidence like internal emails or mimicry of logos/packaging, can strongly favor the trademark owner’s case.

For example, in the earlier Maternally Yours case, the defendant opened a store called “Your Maternity Shop” just blocks away from the plaintiff’s Maternity Shop, with knowledge of the plaintiff’s business. The defendant even imitated the plaintiff’s signage style, packaging, and advertising format: “all with the obvious intention of misleading the public and diverting trade from the plaintiff.” The court noted this bad faith and found it indicative that confusion was intended and likely. Evidence of defendant’s intent to cause customers to associate the two companies strongly weighs toward finding likelihood of confusion.

It’s worth noting that intent is not a required element for infringement. A well-meaning business can inadvertently infringe if their mark is confusingly similar, even if they had no knowledge of the other mark. However, when defendant’s mark choice is made in bad faith (e.g., a former employee of Company A starts Company B with a nearly identical name to siphon customers), courts will not hesitate to infer that confusion was not only likely but the very goal. On the flip side, if a defendant can show they acted in good faith, had no knowledge of the plaintiff’s mark, and picked their mark independently, that won’t necessarily avoid liability, but it will weigh against a finding of likelihood of confusion and may influence remedies. Defendant's intent mainly helps the court gauge how the marks came to be similar; a bad intent usually makes the court more skeptical of the junior user’s arguments.

Not all consumers are alike. The law recognizes that the likelihood of confusion can depend on the level of care or attention the typical buyer exercises for a given product. If the relevant consumers are very careful, highly educated, or making expensive, important purchases, they are less likely to be confused by similar marks. Conversely, if the goods are low-cost items bought on impulse by the general public, the risk of confusion goes up because buyers aren’t researching or deliberating over the purchase.

Courts typically apply the standard of a “typical purchaser exercising ordinary caution”. For everyday inexpensive products (like a snack food), an average buyer might not take much time to discern the brand. If two bags of chips have similar branding, a hurried shopper could grab the wrong one. Here, even slight similarities can confuse consumers who aren’t paying close attention.

On the other hand, consider very expensive or specialized goods, like industrial machinery or luxury real estate. Buyers of those tend to research thoroughly, often know the market players, and are more sophisticated. They are less likely to be misled by similar trademarks because they’ll notice subtle differences. For example, a company selling $50,000 laboratory equipment under the name “LabTech Innovations” might not be confused with “LabTech Instruments” if their customers are procurement experts who investigate each vendor. The degree of purchaser care is higher in that market. As one case noted, if the target buyers are careful, sophisticated purchasers, even marks that are somewhat alike may not cause confusion.

In evaluating this factor, courts consider the typical price of the goods, the conditions of purchase, and the buyer’s expertise. The law expects the purchaser of expensive, specialized goods and services to exercise a high degree of care, reducing the likelihood they’d be confused by mere trademark resemblance.

Beyond the primary factors above, there are other factors and nuances that can influence a likelihood of confusion analysis. Trademark law is flexible, and not all factors carry equal weight in every case. Here are a few additional considerations:

With all these factors, no single factor is dispositive. A strong showing on a few factors can outweigh others. The analysis is holistic: it looks at the totality of circumstances. This flexible approach is why advice from an intellectual property attorney or trademark attorney can be invaluable. They can assess how the factors stack up in your particular situation and compare it to past cases.

A familiarity with the likelihood of confusion standard is useful in the brand selection process. Business owners with a working knowledge of the standard also have a much better chance of avoiding trademark infringement. The key takeaways are: choose a distinctive mark, do your homework with a thorough trademark search, and be mindful if there are other brands in your industry so that you can anticipate and identify potential consumer confusion issues. The multi-factor analysis may seem complex, but it essentially asks the question "Will consumers likely be confused or think there’s an association between two brands?"

If you’re unsure about a new brand name or you receive a cease-and-desist letter alleging your mark is confusingly similar to another, consider consulting a trademark attorney. An experienced attorney can analyze the alleged infringement and advise you of your best course of action. Contact our office for a free consultation to discuss your trademark matters.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

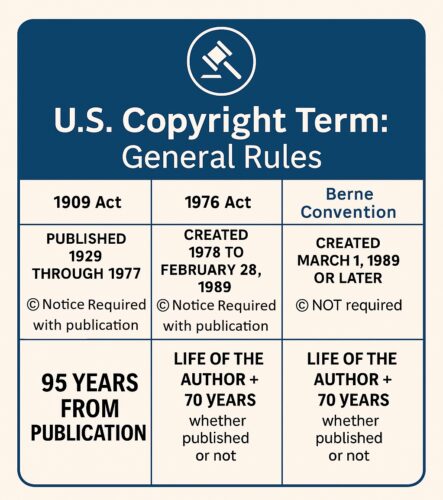

Very few people outside of the copyright legal community understand the difference between a work’s copyright date and its publication date. It is an important distinction with significant legal implications under U.S. copyright law. In simple terms, a copyright date usually refers to the year the copyrights in the work came into being (this varies depending on when the work was created and published), while the publication date is the date the work was first made available to the public. This article breaks down the differences between a copyright date and a publication date, explains how U.S. copyright law treats each, and discusses the practical implications of each across the relevant U.S. copyright acts: the Copyright Acts of 1909, the Copyright Act of 1976, and the Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988. The article's purpose is to help creators, publishers, and businesses better understand the importance of these dates and enable them to protect their creative works.

U.S. copyright law protects original works of authorship as soon as they are “fixed in a tangible medium of expression,” meaning the moment you write down your story, record a song, or save your painting to a canvas, it is automatically protected by copyright. Under current law, you do not need to publish the work or register it with the government for the copyright to exist; the act of creation itself grants the author exclusive rights over the work under copyright law. These exclusive rights include the right to reproduce the work, distribute it, create derivative works, publicly perform or display it, and license others to do the same. Any use of the work by others without permission that falls outside legal exceptions (such as fair use) may constitute copyright infringement, regardless of whether the work has been published or not. Thus, a creative work is protected from the moment of creation, long before any formal publication date or registration date. However, publication and registration are still very important in determining the legal standing and the scope of copyright protection for a particular work.

In everyday language, “publication” often means the publishing date or release date of a book, article, or other work. But in U.S. copyright law, publication has a specific technical definition. Publication is generally defined as “the distribution of copies or phonorecords of a work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending”. Importantly, even offering to distribute copies to a group for purposes of further distribution or public performance constitutes publication, whereas a mere public performance or display (e.g., publicly displaying a painting in a gallery) does not, by itself, constitute publication. In practical terms, publication occurs on the date when copies of the work are first made available to the public without restrictions. For example, if you print and sell a batch of books or release a new song on a streaming service, that act typically counts as publication because copies are being distributed to the public by sale or other transfer. By contrast, if you simply show a painting in a private exhibition or perform an unpublished song live, those acts are not considered publication under copyright law’s definition.

Understanding what constitutes publication is crucial because many aspects of copyright law hinge on whether and when a work was “published.” The date of first publication triggers certain legal obligations and affects the rights of the copyright owner, as discussed below. We will examine how publication plays a role in copyright duration, registration, notice, and the work’s entry into the public domain, and how those implications have changed across different eras of U.S. copyright law.

The term “copyright date” is not explicitly defined in the statute, but it is commonly used to refer to the year associated with a work’s copyright. Typically, the copyright date and the date listed in the work’s copyright notice used to be the same thing, but with the changes that came with the US implementation of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works in 1988, which amended the 1976 Copyright Act. As of March 1, 1989, the notice requirement to establish and maintain copyrights upon publication of a work. Copyright notice is now optional.

A copyright notice is the line that often begins with © (the copyright symbol) and is usually found on the copyright page or title page of a published work (for example, “© 2025 John Doe”). By convention, this year in the notice is the year of first publication of that work. For instance, if a novel was first published in 2025, its copyright notice would normally read “© 2025 [Author/Publisher Name].” The copyright date on the notice informs the public when the work was first released and who the copyright owner was at that time. Business owners should note that the copyright year is typically found in books, on websites, and other creative works to signal when the work was published and that it is protected by copyright law.

It’s important to understand that the copyright notice year is not necessarily the year the work was created. If an author finished writing a creative work (e.g., a manuscript) in 2024 but waited until 2025 to publish it, the publishing date (first publication date) is 2025. However, the copyrights were established in 2024. Sometimes, multiple dates are listed in a copyright notice because of changes to the content of the particular work. For example, if a website’s content is continually updated, the site might display a range of copyright years (e.g., “© 2018–2025”). The changes in the content do not result in the earlier content losing protection, it simply indicates the site includes material up to the current year. The copyright date in the notice serves as an informative date and helps in determining the term of protection for certain works, especially for works made for hire or anonymous works where the term is measured from publication. The copyright date, however, is complicated by changes to copyright law over the course of the twentieth century. Due to the long duration of copyright term and the relative recency of the changes in copyright law, there are currently co-existing works that are subject to different legal regimes based on when they were created and/or published. In older works, the publication date determines the copyright date. These nuances are discussed in further detail below.

Today, including a copyright notice and thus a visible copyright date on published copies is optional but recommended. U.S. law no longer requires a notice to obtain copyright protection. That requirement was eliminated in 1989, but using one has practical benefits. A proper notice informs the world that the work is copyrighted, names the copyright owner, and states the year of first publication, which can prevent an infringer from claiming they didn’t realize the work was under copyright: the “innocent infringement” defense. For works published before March 1, 1989, a valid copyright notice was mandatory, and publishing without a notice could cause the work to enter the public domain immediately. In summary, the copyright date on a work is a public identifier of the work’s first publication year and its claim of copyright. It is not necessarily the date the copyright registration was obtained, since copyright exists upon creation, and thus should not be confused with the date of registration or the exact calendar date of release.

The publication date of a work is the date when the work was first published, as defined by copyright law. In everyday usage, this might be the book’s release date, the date a website or article went live, or the day a music album was released to the public. Legally, the publication date is significant because it’s a fixed point in time that the law uses for several purposes. Generally, one can think of the publication date as the moment the copyright “goes public”: it’s when copies are first made publicly available without restrictions. This date can often be found in the front matter of a book (e.g., “First published in [Month Year]”) or in a record of the publisher. For a website or an online content piece, the publication date might be evident from the posted date or release notes.

It’s worth noting that for many works, the copyright notice year and the first publication year are the same, since the notice reflects the year of first publication. However, the actual full publication date (month and day, or at least month and year) can be important in certain legal contexts. For example, an application to register the work should be filed within three months of the publication date, and thus an accurate publication is needed to calculate a three-month window. Also, different editions or versions of a work can have different publication dates. For instance, if a particular work, such as a book, was first published in 2010, that is the key publication date for copyright purposes. A different book (e.g., a revised edition or a translation of the 2010 book) published in 2015 would have 2015 as its publication date and its own notice year, even if the underlying text was first created earlier. Business owners publishing content should always keep track of the exact first publication date of each work, as this date can affect the duration of copyright and certain legal rights and obligations.

In scenarios where a work was created but not immediately published, the creation date and the publication date diverge. For example, imagine a photographer took a photograph in 2015 but publicly released it for the first time in 2021. In this case, the copyright existed from 2015 (creation), but the publication date is 2021, and that 2021 date would be critical for the copyright application deadline. The publication date is essentially when the work “officially” enters the marketplace or public sphere, which has downstream effects on how the Copyright Office and courts treat the work.

Under the Copyright Act of 1909, which governed U.S. copyright law for works created before 1978, publication was of paramount importance. At that time, federal copyright protection typically began at the moment of publication, assuming the work was published with the proper notice. In fact, if a work was published in the United States without a proper copyright notice under the 1909 Act, the work could instantly fall into the public domain, meaning anyone could use it freely. By contrast, unpublished works were protected by state common law copyrights (a form of protection in equity) until they were published. Publication was the act that triggered federal statutory protection: an author would publish the work with a © notice, and from that date of publication the author had copyrights for a set period of years. Under the 1909 Act, the initial federal copyright term was 28 years from the date of publication with an option to renew for another 28 years. This means the publication date started the clock on the copyrights' duration. If the copyright owner wanted to extend protection beyond the initial term, they had to file a renewal registration in the final year; failing to renew would cause the work to enter the public domain at the end of the initial term.

To illustrate, suppose a book was first published with notice in 1940. Under the 1909 Act regime, its federal copyright would run 28 years from 1940 to 1968 and could be renewed to run for a second 28-year term until 1996. The key point is that the publication date was essentially “day one” of copyright protection under the old copyright law. An unpublished work prior to 1978 had no federal copyright term running because it wasn’t in the federal system until publication. This is a stark difference from modern law.

Also, the requirement of a notice on the published copies meant that the copyright date printed on works (e.g. © 1940) had real legal weight; it indicated that the work was properly claimed under the 1909 Act on that publication date. A missing or incorrect notice could be fatal. As a famous example, the publishers of the film Night of the Living Dead (1968) accidentally omitted the notice when the title was changed at release, causing that otherwise original film to enter the public domain immediately.

It’s also worth mentioning that under the 1909 Act, many works that were not published at all remained under perpetual common-law protection until they were eventually published. This changed with the 1976 Act, which we discuss next. But for our purposes here: if you are dealing with a work first published before 1978, the publication date and whether proper notice was used were critical in determining if the work was copyrighted, for how long, and whether it might have fallen into the public domain due to missed formalities. Attorneys handling legal disputes over older works often must research the publication history and notices of a work to determine its copyright status.

The Copyright Act of 1976, which took effect January 1, 1978, overhauled U.S. copyright law. One of the biggest changes was that copyright protection no longer depends on publication or registration. Instead, copyright protection is automatic from the moment of creation (fixation), and publication is not required to secure copyrights. This brought the U.S. closer in line with international norms, such as the Berne Convention. Under the 1976 Act, works created on or after January 1, 1978 are protected for the author’s life plus 70 years for individual authors, regardless of when or if the work is published. In terms of when the law says copyright protection starts, the copyright date is now the date of creation, not publication. You could write a story today and never publish it; it would still be a copyrighted work until it eventually expires many decades later.

In 1988, Congress passed the Berne Convention Implementation Act, which took effect on March 1, 1989. This legislation eliminated the requirement that published works include a copyright notice in order to receive federal copyright protection. Prior to that date, omission of a proper notice could result in immediate forfeiture of copyright protection for published works under the 1909 and 1976 Acts. After March 1, 1989, notice became optional, but still recommended, for works first published in the U.S. This amendment was essential for U.S. adherence to the Berne Convention, which prohibits signatory countries from conditioning copyright protection on compliance with formalities such as registration or notice.

The publication date still remains very significant under the 1976 Act and its amendments, but in different ways. For example, for works made for hire or anonymous/pseudonymous works, often owned by companies or published under a corporate name, the copyright term is defined as 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first. In these cases, the year of first publication can indeed determine the length of protection. If a company creates a work and publishes it immediately, the clock runs 95 years from that publication year. If the company never publishes the work, the term would max out at 120 years from creation. Thus, even in the modern regime, knowing the exact first publication date is essential for calculating when a work will enter the public domain for certain types of works.

Additionally, the 1976 Act and subsequent amendments preserved special rules for works that were created before 1978 but not yet published by that date. Section 303 of the current law provided that pre-1978 unpublished works were given a default term lasting at least until 2002, and if such a work was first published between 1978 and the end of 2002, it wouldn’t expire before 2047. This was to ensure that older manuscripts, letters, or artwork that remained unpublished as of 1978 didn’t suddenly lose protection. In essence, Congress gave those works a window to be published without penalty. The details are complex, but the key takeaway is that for certain older works, the first publication date can affect whether the work is still under copyright today.

In summary, under modern U.S. law, the publication date does not start copyright protection, since protection starts at creation, but it does trigger other legal effects. Among these are the requirement to deposit copies with the Library of Congress, the timing of registration relative to publication, and the applicable duration for certain works. Also, as mentioned earlier, after 1978 the law gradually eliminated formalities like the notice requirement. So while you might still see a “© 2025” on a book’s title page as the copyright date, that is there to inform and deter infringers, not as a condition of protection. The copyright owner is still wise to include it, as it helps identify the owner and year for anyone who needs to seek permission to use the work, and it may ward off claims of innocent infringement. But if somehow the notice is omitted on a work first published after 1989, the work is still protected: omission no longer forfeits copyright.

It is important to distinguish copyright registration from publication. Registration is the process of filing a claim with the U.S. Copyright Office, and it results in a certificate with an official effective date of registration. This date is essentially when the Copyright Office received all required materials in the proper form. Many people casually refer to “registering a copyright” or getting a “copyright date” from the government. In reality, registration is optional for copyrights to exist, but it is mandatory if you want to enforce your rights in U.S. court and enjoy the full benefits of copyright protection. Think of registration as a way to strengthen and activate your copyright’s legal standing: you already have the copyright upon creation, but you cannot sue for copyright infringement in the U.S. until you have either registered the work or at least applied and been refused registration.

The copyright registration date does not need to coincide with the publication date. You can register an unpublished work, or you can register after publication. For example, a photographer might publish a photo on their website today, but wait to file an application to register copyrights in the photo with the Copyright Office next month. The application date becomes the effective date of registration, if the registration issues. Ideally, authors and businesses should register their works promptly, because registration timing has practical implications. If a work is registered before an infringement or within three months of publication, the copyright owner is eligible to seek statutory damages and attorney’s fees in an infringement lawsuit. If you wait longer than three months after first publication to register and someone infringes in the meantime, you might lose the chance to claim those enhanced remedies for that period of infringement. You could still stop the infringement and get actual damages, but statutory damages are a powerful remedy you’d forgo if registration was not timely.

To put it plainly: the publication date is when the world first sees your work; the registration date is when you officially record your claim with the U.S. government. The law rewards timely registration relative to publication. The Copyright Act provides a three-month grace period after first publication during which you can file for registration and still be able to recover full remedies (statutory damages and fees) even if the infringement began in that window. This is why you’ll hear advice such as “register your work within 90 days of publication.” It’s not because copyright protection would lapse, but because your legal remedies in court can be limited if you miss that window. In order to take advantage of the full benefits of copyright registration, your works should be registered at the earliest opportunity.

Another connection between registration and publication is evidentiary: if you register within five years of first publication, your registration certificate will serve as prima facie evidence of the validity of the copyright and the facts stated in it, in any court dispute. This means courts will presume your claims (e.g., authorship and ownership) are true, putting the burden on others to prove otherwise. Registering many years after publication can weaken that presumption. Thus, while the copyright date in the notice is mostly for informing the public, the registration date is crucial for legal enforcement.

The publication date of a work can also influence how long the work remains protected, i.e., when it enters the public domain. The rules differ based on the type of work and when it was created. As noted, for individual authors under today’s law, the term is life of the author plus 70 years, and publication date doesn’t change that. For example, if a company released a training video in 1980 as a work made for hire, the copyright would last through 2075 (95 years from 1980). If that video was created in 1980 but not published until 1990, then 95 years from 1990 (i.e., until 2085) would be the term, unless 120 years from creation (which would be 2100) comes first. In that case, 2085 is earlier, so the term ends 2085. The takeaway is that for certain works, both creation and publication dates are needed to determine the exact expiration.

Under older laws, as discussed, works had fixed terms from publication (28 years, renewable to 95). Laws passed in 1976 and 1998 extended those terms. As of today, any work first published in 1929 or earlier is definitely in the public domain in the United States due to expiration of term. For example, works published in 1929 entered the public domain on January 1, 2025, after their maximum 95-year copyright term expired. Each year on January 1st, another year’s worth of works (95 years old) fall out of copyright. This schedule is tied directly to the publication year for works from 1923 through 1977, because those works have a term of 95 years from publication (assuming they were properly renewed, etc.). Thus, knowing a work’s first publication date is essential when assessing if it might be public domain. Librarians and researchers often use publication dates as a guidepost for determining public domain status. For instance, as of now, a U.S. book first published in 1930 would be under copyright until the end of 2025 (95 years from 1930), entering the public domain on January 1, 2026, unless something like a missing notice already caused it to fall into public domain earlier.

Conversely, unpublished works were given special treatment so that many of them did not enter the public domain until recently. An unpublished manuscript from 1880, for example, which had never been published or registered, would have been protected by common law until 1978, then got at least until 2002 under the 1976 Act, and if the author was unknown or long deceased, it would have entered the public domain on January 1, 2003 if still unpublished. If it was first published before 2003, it got protection until at least 2047. These examples illustrate that publication dates can extend or limit protection for older works under the transitional provisions. In everyday practice, for works created now, publication date’s main impact on duration is (1) for those work-for-hire/anonymous cases, as noted, and (2) for works from the mid-20th century, the copyrights of which are tied to their publication year.

Beyond duration and formalities, whether a work is considered published or unpublished can affect certain uses and exceptions in copyright law. For example, the fair use doctrine under 17 U.S.C. §107 considers whether a work is unpublished as part of the analysis. Unpublished works get a bit more leeway in favor of the author in some court decisions, as authors have a right to control first publication. Likewise, Section 108 of the Copyright Act provides special rules for libraries and archives: libraries can make preservation copies of unpublished works more freely, since an unpublished work might not be commercially available at all. But for published works, libraries have a different set of rules for archiving and lending. Another example is the right to publicly perform sound recordings via digital audio transmissions (17 U.S.C. § 114); published versus unpublished status can matter for certain statutory licenses. The general theme is that the law sometimes distinguishes between published and unpublished works, granting unpublished works different treatment in certain contexts because distribution to the public has not occurred.

From the perspective of a business or creator, this means that choosing when and if to publish a work can have implications. Once a work is publicly distributed, it is considered published and those special considerations for unpublished works fall away. Additionally, the act of publication might involve other transfers of rights or ownership. For example, if you have a publishing contract, the publisher might become the copyright owner upon publication by transfer. The ownership and licensing arrangements often hinge on publication as well. For example, a photographer might license first publication rights to a magazine. While these issues go beyond just dates, it’s important to see that “publication” in copyright isn’t merely a formality; it is a status that can change how the law treats the work in various scenarios.

Understanding the distinction between copyright dates and publication dates is not just academic, it helps you manage your intellectual property strategically. Here are some practical takeaways and tips:

By following these practices, business owners and creators can ensure their works are properly protected and that they maximize the legal benefits available under copyright law. Always remember that copyright law, while federal and relatively uniform across the U.S., can be complex. The stakes (e.g., in legal disputes over infringement or ownership) can be high when valuable content is involved.

For U.S. business owners and creators, knowing the critical dates for copyright materials is a must to effectively manage intellectual property assets. For further information, the U.S. Copyright Office provides useful circulars and resources. Consulting with a qualified copyright attorney can help to effectively address copyright issues. If you have a copyright matter or other intellectual property issues to address, contact our office for a free consultation.

© 2025 Sierra IP Law, PC. The information provided herein does not constitute legal advice, but merely conveys general information that may be beneficial to the public, and should not be viewed as a substitute for legal consultation in a particular case.

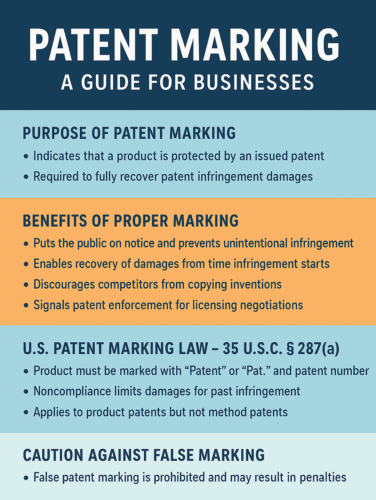

Patent marking is the practice of labeling products with patent information, typically the word “Patent” or “Pat.” followed by a patent number, to notify the public that the product is protected by an issued patent. For business owners new to patent law, understanding patent marking is crucial. Proper marking serves multiple purposes: it provides notice to the public of a product’s patent protection, helps preserve the patent owner’s rights to recover damages for patent infringement, and can deter competitors from copying the patented invention. In the United States, while patent marking is technically optional, it is highly recommended as a best practice for anyone who sells a patented product and may need to enforce their patent rights. This article offers an overview of U.S. patent marking laws, the benefits of marking, how to mark products (including “patent pending” notices and virtual marking), and the pitfalls of false marking.